Pop Art

Neo-Dada for the masses

Pop Art is the use of commercial art as a subject matter in painting, I suppose. It was hard to get a painting that was despicable enough so that no one would hang it – everybody was hanging everything. It was almost acceptable to hang a dripping paint rag, everybody was accustomed to this. The one thing everyone hated was commercial art; and apparently they didn’t hate that enough either.

Roy Lichtenstein, 1963

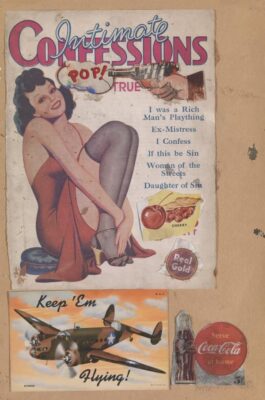

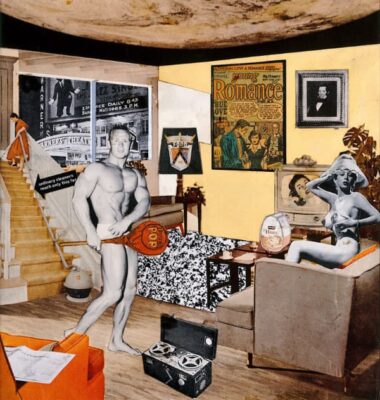

European Proto-Pop: Eduardo Paolozzi, “I was a Rich Man’s Plaything”, 1947. Collage, Tate Gallery. © The estate of Eduardo Paolozzi ·· Richard Hamilton, “Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?“, 1956. Kunsthalle Tübingen. © The estate of Richard Hamilton

Once the wounds of the Second World War had healed, the United States and Europe experienced a long period of economic growth which, together with technological advances and the general atmosphere of euphoria after the anguish of the War, led to a boom in consumption and entertainment never before seen in the middle class. Cinema and television, magazines and comics, Marilyn and Superman entered the home, and a new iconography of fast, casual, accessible, anti-elitist and even banal consumption appeared, on which artists were quick to focus their attention.

On the other hand, in the chapter on 19th-century Realism and Academicism, it was noted how art, in addition to showing a great capacity to reflect the ideals and spirit of the society of its time (the zeitgeist), seems to respond to a principle of action-reaction in which the existence of a style or movement irremediably prepares the appearance of a subsequent movement with characteristics generally opposed to the preceding one. In this respect, it could be said that by the end of the 1950s, society was beginning to tire of the sometimes indecipherable intellectualism of Abstract Expressionism and Color Field. In this sense, “young artists accused Abstract Expressionism of having reached a stage characterised by emotional insincerity and academicism. On the other hand, the public was beginning to tire of abstract rhetoric, based on paintings without structure” (Historia del Arte, Salvat Editores, Vol. 10).

A few years after the Second World War, Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005), a Scottish resident in London who had been familiar with the works of Jean Arp and the Dada circle, finished “I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything“, a collage based on cuttings from American magazines that can be considered a direct forerunner of Pop Art. Paolozzi’s collages were the origin of the so-called Independent Group, a group of artists (whose production was heterodox and somewhat intermittent) who decided to explore the artistic possibilities offered by elements taken from the mass media. Among them was Richard Hamilton (1922-2011), who in 1956 created his “Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?“, conceived for the cover of the catalogue of the “This Is Tomorrow” exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, and often considered the first true work of Pop Art.

American Pop Art: Roy Lichtenstein, “Look, Mickey”, 1961. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington. © Artists Rights Society, New York ·· Andy Warhol, “Campbell’s Soup Cans”, 1962. Museum of Modern Art. © Artists Rights Society, New York

Pop Art began in the United States with the figures of Jasper Johns (b.1930) and Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008). The former began experimenting with collage in the first half of the 1950s and, “being told that they resembled those of Kurt Schwitters [a German Dada artist who died in 1948], he began to study Schwitters’ work and saw that they resembled his own. He was trespassing, and he veered away – to be different” (Leo Steinberg: “Jasper Johns: the First Seven Years of His Art”, 1961). 1954 was a key year for Johns, when, in search of his own path, he began to paint his now famous “Flags”, and also met Robert Rauschenberg at the Leo Castelli Gallery, with whom he would begin a professional and sentimental relationship. Rauschenberg, who had experimented with Abstract Expressionism in the early 1950s, began to introduce “Pop” and “banal” elements into his “Combines”, a practice he would continue until the early 1960s.

It was in the early 1960s that Pop Art reached maturity in the United States. In 1961 Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1977) painted his “Look Mickey” (Washington, National Gallery), the beginning of his famous series of works in which comic book images are transferred to canvas, sometimes on a monumental scale, as in “Whaam!” (1963, London, Tate Modern). Lichtenstein’s style was initially met with harsh criticism and derision, and Life magazine, which in 1949 had asked of Jackson Pollock, “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?“, published a review of Lichtenstein in 1964 asking “Is he the Worst Artist in the U.S.?“. Today, there is still debate about the originality of Lichtenstein’s work. While the art market has placed him as one of the most sought-after artists of the 20th century (his 1962 “Masterpiece” was sold for $165 million in 2017), artists such as Dave Gibbons have parodied Lichtenstein’s work, doubting that they are worth more than the comic strips they are inspired by.

The most famous figure of the movement, the man who brought the essence of Pop Art into his own personal life, was Andy Warhol (1928-1987). More than any other artist of his time, Warhol was able to feed off the popular icons of his time (from Marilyn Monroe to a Coca-Cola bottle) to become, in his own words, an art-creating machine: “The reason I’m painting this way is that I want to be a machine, and I feel that whatever I do and do machine-like is what I want to do“, he wrote in 1963. Paint like a machine, repeating a work as many times as society demands, make money, and then choose a new icon in order to repeat the process. Warhol’s art, the direct heir of Duchamp and his ready-mades, “it is art stripped of personality and emotion and concerned only with the image, the obvious. It is art of the machine, not about the machine” (Paul Bergin, “Andy Warhol: the Artist as Machine”, 1967).

David Hockney: “A bigger splash”, 1967. Oil on canvas, 243 x 243 cm. London, Tate Modern. © David Hockney / Artists Rights Society, New York ·· Claes Oldenburg: “Floor Burger”, 1962. New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) © Claes Oldenburg / Artists Rights Society, New York

Along with Warhol and Lichtenstein there were other noteworthy figures in American Pop Art. Tom Wesselmann (1931-2004) reinterpreted the tradition of the Western female nude in a Pop style. British by birth but resident in California since 1964, David Hockney (b.1937) borrowed elements from Pop Art, but without renouncing creativity and pictorial originality, as did Wayne Thiebaud (b.1920). Other notable artists include Corita Kent (1918-1986), Robert Indiana (1928-2018), James Rosenquist (1933-2017), Jim Dine (b.1935) and Ed Ruscha (b.1937). In sculpture, the multifaceted Marisol Escobar (1930-2016), was the author of some of the most important sculptures of the heyday of American Pop Art, such as “The Family” or “The Party“. The everyday figures of Claes Oldenburg (b.1929) opened the door for later artists such as Jeff Koons (b.1955).

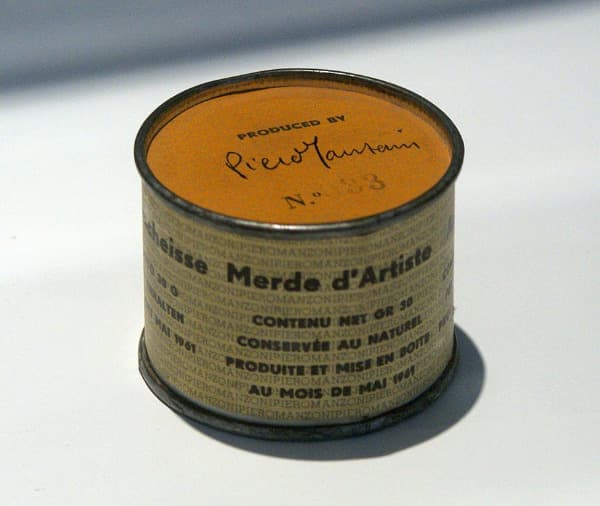

In Europe, after the aforementioned cases of Paolozzi and Hamilton, Pop Art appeared intermittently and in a rather disorganised way. The French Nouveau réalisme of the 1960s has sometimes been associated with Pop, although figures such as Yves Klein or Pierre Restany can hardly be identified as “Pop artists”. Ronald Kitaj (1932-2007), an American in the United Kingdom (the opposite of David Hockney, mentioned above) continued Hamilton’s collage practice, but with a focus on abstraction. In Italy, artists such as Piero Manzoni (1933-1963) and Valerio Adami (b.1935) were influenced by Pop Art but leaned more towards conceptual art. In Spain, the late 1960s and early 1970s saw the emergence of Eduardo Arroyo (1937-2018) and the so-called Equipo Crónica (active from 1964 to 1981).

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: