Abstract Expressionism

Inner energy turned into a gesture

The modern artist is living in a mechanical age and we have a mechanical means of representing objects in nature such as the camera and photograph. The modern artist, it seems to me, is working and expressing an inner world – in other words – expressing the energy, the motion and the other inner forces.. ..the modern artist is working with space and time, and expressing his feelings rather than illustrating..

Jackson Pollock, 1950

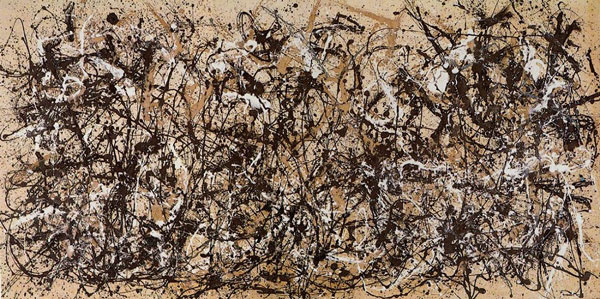

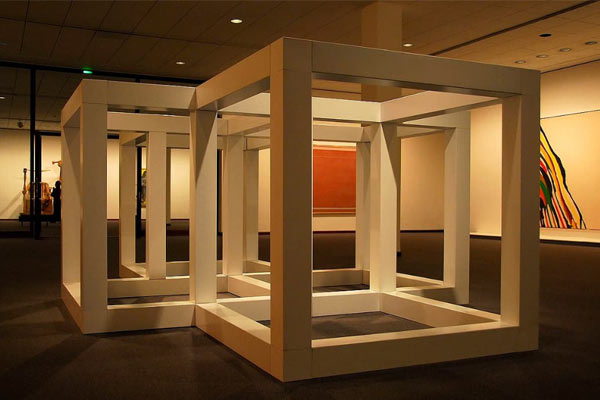

Abstract Expressionism: Jackson Pollock, “Autumn Rhythm”, 1949. Enamel paint on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art. © Artists Rights Society, New York ·· David Smith, “Cubi XIII”, 1963. Princeton University

During the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century, Paris was the artistic capital of the world and the main destination for young artists from all over the world and, as a result, most of the most important movements and styles of modern art, from Impressionism to Surrealism, were born in the French capital. However, as the twentieth century dawned, the thriving New York began to dispute its throne, propelled by an unprecedented demographic and economic growth. New York was not only an economic powerhouse, but also possessed a youthful brashness and the open-mindedness of a city of immigrants. As early as the late 19th century, the city’s major art buyers -including the then recently opened Metropolitan Museum- travelled to Europe in search of art from the Old Continent, banking on the then lesser-appreciated Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works. Attracted by this open and dynamic atmosphere, during World War I several avant-garde artists -such as Marcel Duchamp or Francis Picabia– made stays in New York, exchanging ideas directly with American art, then dominated by the realism of “The Eight” and the Ashcan School.

In the interwar period two figures arrived in New York who would be essential in the genesis of Abstract Expressionism: the Armenian Arshile Gorky (1904-1948) and the German Hans Hofmann (1880-1966). Another fundamental event of this period was the opening of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which played a fundamental role in the development of modern American art. Between 1936 and 1937, MoMA presented three consecutive exhibitions devoted to “Cubism and Abstraction,” “New Horizons of American Art,” and “Surrealism and Dada,” three themes that paved the way for the great American art movement of the following decade.

In the years leading up to the outbreak of World War II, the growing climate of fear led an increasing number of artists to leave Paris and seek refuge in quieter lands. With the threat of the spread of German National Socialism sweeping across Europe, America seemed the safest destination. Between 1939 and 1940 the surrealism of Salvador Dalí and the abstract art of Piet Mondrian arrived in New York, as did the abstract surrealism of Roberto Matta, as well as other avant-garde figures such as Marc Chagall, Max Ernst and Fernand Léger. In short, everything seemed to indicate that, for the first time in history, the next dominant artistic movement in Western art would not be born in Europe, but in America. And so it was when, even before the end of the Great War, Abstract Expressionism appeared in New York.

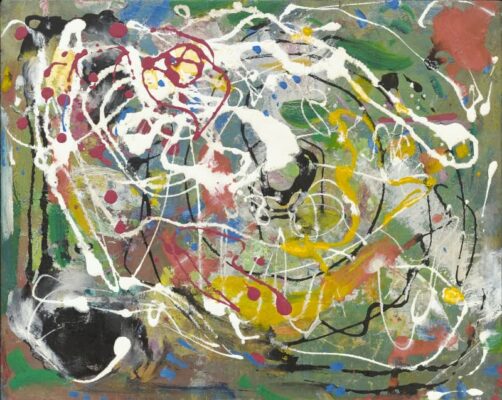

Origins of Abstract Expressionism : Arshile Gorky, “The Liver is the Cock’s Comb”, 1944. Oil on canvas, Albright–Knox_Art_Gallery. © Artists Rights Society, New York ·· Hans Hofmann, “Spring”, 1944-45. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) © Artists Rights Society, New York

It has been said that Abstract Expressionism was the first great purely American artistic style, and although this is not entirely true (such honour should go to tonalism), it was the first dominant style born in the United States. However, when speaking of its protagonists we must begin with two artists of European origin, the aforementioned Arshile Gorky (1904-1948) and Hans Hofmann (1880-1966). Gorky, who during his early career experimented in a wide range of styles, from Impressionism to Cubism, began to develop towards the end of the 1930s a style of lyrical abstraction, which the painter Adolph Gottlieb defined as “a wedding of Abstraction and Surrealism. Out of these opposites something new could emerge, and Gorky’s work is a part of the evidence that this is true. What he felt, I suppose, was a sense of polarity, not of dichotomy; that opposites could exist simultaneously within a body, within a painting or within an entire art.” Gorky’s work would influence virtually all Abstract Expressionist artists, especially Willem de Kooning, who will be discussed later. For their part, the abstract works created by Hans Hofmann in the early 1940s won critical and public acclaim when exhibited at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century Gallery, and encouraged other painters to experiment with abstraction. As Pierre Restany (“Abstract Expressionism”, 1984) rightly pointed out, Hans Hofmann was the artist who acclimated Germanic Expressionism to the United States, so that “Hoffman was to lead many young artists to take the great leap, to engage in a painting of direct expression“. With the example of Gorky and Hofmann, the foundations for the definitive explosion of Abstract Expressionism were already in place.

The most important of all Abstract Expressionist figures was Jackson Pollock (1912-1956). Born in Wyoming, but raised in Arizona and California, his works created before 1945 were influenced by both Native American culture and Mexican muralists. Between 1947 and 1950 Pollock reached his artistic maturity, the drip period, in which, pouring paint directly from the can onto the canvas -usually laid out on the ground- he created works of impressive force that show, in the words of Pierre Restany, “the full mastery of the ‘over all’ and of the sense of scale and of psychic and nervous energy transformed into gesture“. For the drip, Pollock was almost certainly inspired by the artist Janet Sobel, who was already using this technique in the mid-1940s. After this brief but intense period, Pollock abandoned the drip, and his later works lack the interest of his earlier ones, with notable exceptions such as the “Blue Poles” of 1952.

Abstract Expressionism: Jackson Pollock, “Blue Poles”, 1952. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Australia © Artists Rights Society, New York ·· Willem de Kooning, “Woman I”, 1950-52. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) © Artists Rights Society, New York

In the early 1940s, Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) -an artist born in the Netherlands but who lived in the United States since he was 22 years old- showed the influence of Gorky in his abstractions with biomorphic shapes, but it was from 1950 onwards when he achieved his maturity in his “Women” series, temporarily recovering figuration before returning to abstraction from 1953 onwards. Other notable figures of the heyday of Abstract Expressionism are Franz Kline (1910-1962) and his large black and white abstractions, as well as Robert Motherwell (1915-1991). Among the painters who continued to experiment with Abstract Expressionism during the 1950s were Clyfford Still (1904-1980) and Philip Guston (1913-1980).

Women played a very relevant role in Abstract Expressionism. The work of Lee Krasner (1908-1984) was for a long time obscured by the fame of her husband, Jackson Pollock, only to be recognized as it deserves six months after his death, as a result of a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Younger than the other Abstract Expressionist painters, Joan Mitchell (1925-1992) nonetheless achieved recognition quite early, even exhibiting in the “Ninth Street Show,” organized by Leo Castelli in 1951. Even younger than Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) was initiated in Abstract Expressionism, but excelled especially in Color Field painting, which we will discuss later.

In the field of sculpture, Abstract Expressionism is usually associated with the work of Alexander Calder (1898-1976) and John Chamberlain (1927-2011), although the most outstanding figure, who best knew how to transfer the spontaneous energy of Abstract Expressionism to the three dimensions, was David Smith (1906-1965).

Color Field: Mark Rothko, “Yellow Expanse”, 1953. Private collection. © Artists Rights Society, New York ·· Helen Frankenthaler, “Mountains and Sea”, 1952. National Gallery of Art, Washington. © Artists Rights Society, New York

Color Field painting originated at the same time as Abstract Expressionism (to be precise, a few years later), and there is some debate as to whether it should be considered part of it. As opposed to the rabid gestural lines and strokes of Abstract Expressionism, the Color Field artists opted for large masses of color, often uniform, occupying the surface of the canvas. At the same time that Pollock created his most energetic “drips”, Barnett Newman (1905-1970) painted in 1948 his “Onement 1”, whose message was captured by Mark Rothko (1903-1970), the most notable and famous of all the “Color Field” painters, a painter who, according to his own words, sought with his paintings “to express basic human emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, doom“. For Rothko, color, “although not a final aim in itself, is his primary carrier, serving as the vessel which holds the content. The color may be savage, at times burning intensely like sidereal landscapes, at others giving off an enduring after-glow (…) There is almost no limit to the range and breadth of feeling he permits his color to express” (Peter Seltz: “Mark Rothko”, 1961).

In addition to the aforementioned Helen Frankenthaler, the legacy of the “Color Field” was continued by Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993), who was part of the Bay Area Figurative Movement during the 1950s, but who in the 1960s recovered the principles of the “Color Field” in his “Ocean Park” series of paintings.

At the same time as American Abstract Expressionism, Tachism (sometimes called Tachisme or Lyrical Abstraction) developed in Europe (more specifically in France), characterized, like Pollock’s “action painting,” by the direct application of paint from can to canvas. While many prominent Abstract Expressionist painters were European-born Americans, arguably the most talented figure of Lyrical Abstraction, Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923-2002) was actually a Canadian-born painter who worked for much of his career in France, exhibiting as a “European artist” at the Guggenheim Museum in 1953. In addition to Riopelle, the figures of Pierre Soulages and Nicolas de Staël (1914-1955) should be mentioned, as well as the artists of the Cobra Group, especially Karel Appel (1921-2006).

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: