Art Museums – acquiring in the age of petrodollars

by G. Fernández – theartwolf.com. Published in June 2019.

Looking at the history of art collecting in modern times, it is not inaccurate to say that, until relatively recently, the most powerful “hunters” of art masterpieces were the great museums, especially the American institutions. In 1961, the Metropolitan Museum broke all records for the acquisition of a work of art by purchasing Rembrandt‘s excellent “Aristotle with a Bust of Homer” for $2.3 million. Six years later, the same museum beat several private bidders and purchased Monet‘s “Terrasse à Sainte-Adresse” for £588,000, then a spectacular price for an Impressionist painting. And in 1970, a new auction record was broken when Velázquez‘s “Juan de Pareja” sold for £2.3 million ($5.54 million) and was again acquired by the Metropolitan Museum.

Two works by Leonardo da Vinci: the portrait of “Ginevra de’ Benci”, and the “Salvator Mundi” (attribution disputed). Both works smashed the record price for a work of art, at very different times. The former is now on display in a national gallery. The second is possibly hidden away on a yacht.

Meanwhile, in 1967 the National Gallery of Washington made one of the most spectacular acquisitions of all time by buying Leonardo da Vinci‘s portrait of “Ginevra de’ Benci” from the Prince of Liechtenstein for a price close to or over $5 million, doubling the previous record price for a work of art. The painting, which had been coveted by many museums and private collectors, was sold to the American museum for no diplomatic or political reason. As the Prince himself admitted in an interview with Stefano Pirovano of conceptualfinearts, “we were simply looking for the best buyer“.

And also in the United States, of course, the Getty, always the Getty, the wealthiest museum in the world, breaking records both for antiquities ($4 million paid in 1977 for its “Victorious Youth“) and for paintings, shelling out $10.5 million for Andrea Mantegna‘s “Adoration of the Magi” in 1985. Two years later, the Kimbell Museum in Fort Worth paid an unknown sum (but possibly close to $15 million) for Caravaggio‘s “The Card Players“.

In Europe, the situation was not much different. When Titian‘s “The Death of Actaeon”, an important poesie by the Venetian master, came up for auction in 1971, fetching £1.7 million, the National Gallery of London managed to prevent the Getty from taking it to California by matching its bid. A similar success was achieved in 1980, when the British gallery acquired Rubens‘ “Samson and Delilah” for around $5 million.

The end of an era: from the Japanese boom to the petrodollars

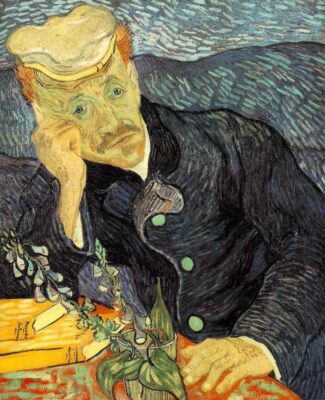

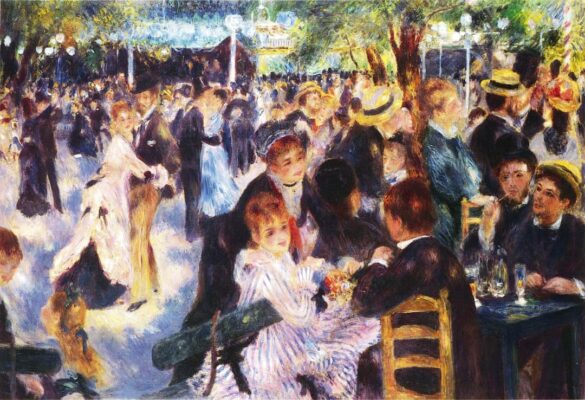

In 1987, Sotheby’s announced the sale of one of Vincent van Gogh‘s “Sunflowers“, hoping to fetch around $16 million and surpass the $11 million paid the previous year for a Manet. The painting was subsequently sold for almost $40 million to Japanese tycoon Yasuo Goto. This was the beginning of the Japanese fever for Impressionist and modern paintings, which reached its peak in 1990, with Ryoei Saito paying $82.5 million for Van Gogh’s “Portrait of Doctor Gachet” and $78.1 million for the smaller version of Renoir‘s “Dance at the Moulin de La Galette“. Although this boom was short-lived (by 1992 Japan was already entering its “lost decade”), it marked the moment when the major museums lost their leading position in art collecting.

Once the crisis of the early and mid-1990s was over, new players entered the market. The great American tycoons (Steve Wynn, Steve Cohen…), the new Russian millionaires (Roman Abramovich) and Asian buyers were prepared to pay extraordinary sums for the most important paintings, making them unaffordable for museums. Already in 2007, Lee Rosenbaum wrote in the Los Angeles Times that museums could not compete with the big private collectors. The recent sale of the “Salvator Mundi” attributed to Leonardo da Vinci for an incredible $450 million is just the latest episode in this hitherto unstoppable rise in the price of great masterpieces.

So what are the major museums doing to enrich their collections with this seemingly unbeatable competition? Let’s look at the different cases.

United Kingdom: saving for the nation

The collections of the British nobility hold some of the most important Old Master paintings in private hands. In recent years, the British government has made many efforts to prevent these masterpieces from being sold to foreign buyers. Given the high quality of some of the British collections, some of these ‘saved’ works are genuine masterpieces, and their acquisition was considered a “matter of state”. Theartwolf.com published an extensive article a few years ago on masterpieces saved by the UK, so here we will only pick out a few of the most prominent cases.

Titian: “Diana and Callisto” and “Diana and Actaeon”, 1556-59. Oil on canvas, 187 × 204.5 cm and 185 cm × 202 cm

Undoubtedly the most important of the works that the UK has acquired are two pictorial “poesies” by Titian, “Diana and Callisto” and “Diana and Actaeon”, formerly in the collection of the Duke of Sutherland (who also owns important works by Raphael and Rembrandt). Thanks to contributions from, among others, the National Gallery itself (whose holdings were then “empty”, as the gallery director said), the National Heritage Memorial Fund, and anonymous private individuals, both paintings were acquired between 2008 and 2012 for some £50 million each, well below their open market price.

The payment in lieu of taxes is one of the formulas used by the United Kingdom to acquire works whose value on the open market would have been much higher. A clear example was the case of Cimabue‘s “Madonna Enthroned with Child” (known as the “Benacre Hall Madonna“). When the work was put up for auction by its owners in 2000, the National Gallery initiated a campaign to delay the sale, and eventually the government accepted the work as a tax payment from The Gooch Estate. The work was withdrawn from auction and sold to the London Gallery for around $8 million.

Spain and Italy: taking advantage of closed markets

Spain and Italy also have a considerable artistic heritage in private hands. But unlike the UK, both countries have laws that prevent a work declared a national treasure from being sold to a foreign buyer. In the case of Spain, this legislation has enabled the Prado Museum to acquire works of extraordinary importance: Goya‘s “Countess of Chinchón“, acquired for around 25 million euros in 2000 (and for which the Getty Museum had offered almost twice as much a few years earlier), Fra Angelico‘s “Virgin of the Pomegranate” (acquired in 2016), and what is perhaps the best acquisition made by a museum so far this century (taking into account the importance of the work and the price paid): Pieter Brueghel the Elder‘s “The Wine of Saint Martin’s Day“, acquired for around seven million euros in 2010. We will never know how much this painting would have fetched had it been sold on the open market. Personally, anything less than 50 million euros seems to me to be too conservative.

More modest, but also important, was the acquisition in 2000 of “Santa monaca con due fanciulle” by Paolo Uccello, acquired for 1.3 million euros at an auction at Finarte Milan and deposited in the Galleria degli Uffizi. Despite its modest size, given the scarcity of works by the artist on the market, the painting could easily have fetched over €5 million if it had been auctioned in London or New York.

American museums: discretion as a strategy

By avoiding auctions, where prices for major works of art can soar to unreasonable levels, American museums (with the exception of the Getty) have tended to stay away from public sales and negotiate discreetly with the owners of the works they are interested in. One of the most famous museum acquisitions of recent times has been Duccio‘s “Madonna and Child“, known as the “Stoclet Madonna“, formerly the only work by the artist in private hands, whose acquisition (for around $45 million) was announced by the Metropolitan Museum in 2004, after several years of negotiation with the owners. Similarly, in 2013 the National Gallery of Washington acquired “The Concert”, perhaps the most important painting by Gerrit van Honthorst, for a price of around $20 million, negotiating directly with its owners.

Strength in unity: Rembrandt’s twin portraits

When in 2014 the Rothschild family decided to sell Rembrandt‘s “Wedding Portraits of Marten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit“, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Louvre in Paris joined forces in order to acquire the pair, which would have been impossible to do separately, given the high price (160 million euros) of the pair of portraits. Wim Pijbes, director of the Rijksmuseum, stated that the paintings will not be separated, and that each museum owns 50 percent of each painting, so it is assumed that the pair of paintings will travel regularly between Amsterdam and Paris.

Follow us on: