Caspar David Friedrich

The landscape as a manifestation of the sublime, loneliness of man in the face of the inevitability of his death, references to Germanic folklore and, in short, the whole zeitgeist of German Romanticism come together as in no other figure in Caspar David Friedrich, a solitary and even misanthropic painter, of whom the sculptor David d’Angers wrote that he had discovered “la tragédie du paysage“.

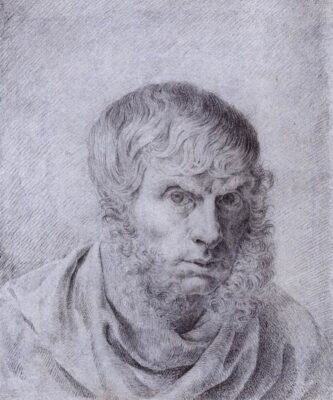

Imagen: Caspar David Friedrich: “Self portrait”, c.1810. Gray chalk on paper, Kupferstichkabinett Berlin

This “tragic landscape” to which d’Angers referred represents a departure from the tradition of European landscape painting -Van Ruysdael, Hobbema… – in which nature was represented objectively, often as a background or location for human activity. In the new concept of landscape that began with Friedrich, the romantische Stimmungslandschaft, the relationship between man and nature is spiritual, the latter being the manifestation of the divine (“The divine is everywhere, even in a grain of sand“, wrote Friedrich) and landscape thus acquires a metaphysical dimension.

Caspar David Friedrich was born in Greifswald, a village on the Baltic Sea, in 1774. His family suffered various misfortunes (including the death of his mother and two of his brothers) during his childhood. He received his first drawing lessons in his early teens and at age twenty he entered the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Denmark. After completing his training, he moved to Dresden in 1798.

Friedrich’s first notable works date from 1807-08. “Dolmen in the Snow” (1807, Galerie Neue Meister) and “Cross in the Mountains” (known as “Tetschen Altar”, 1808, Staatlichem Museum Dresden) clearly show the continuous reference to death in Friedrich’s paintings, although with interesting thematic differences between the two works. While the former features elements of German folklore (the cairn in a winter forest), the latter -finished at Christmas 1808- includes Christian iconography in a landscape. The following year Friedrich painted “The Abbey in an Oakwood” (1809, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin), in which the idea of death is present both in the tombs and the half-ruined abbey and in the bare branches of the trees in the winter landscape. Thus, in this painting “the theme of death, linked to that of religion and that of the mysterious and solemn nature, is imposed in an association of ideas that transcends the representation of the landscape by itself” (Javier Arnaldo, “Caspar David Friedrich”, 1993).

Caspar David Friedrich: “The Abbey in the Oakwood”, 1809. Oil on canvas, 110.4 x 171 cm. Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin ·· Caspar David Friedrich: “The Monk by the Sea”, 1809. Oil on canvas, 110 x 172 cm. Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Why, the question is often asked of me

Do you choose as subjects for painting

So often death, perishing and the grave?

In order to one day live eternally

One must often submit oneself to death.

Caspar David Friedrich

From the same year (although it is possible that Friedrich had already been working on it for some time) is “The Monk by the Sea”, one of his most famous works, which Marie Helene von Kügelgen, wife of a painter friend of Friedrich’s, described as “a vast, infinite, aerial space“, adding that for the painting “a storm would be a relief, for then life and movement could be seen somewhere…”.

Friedrich lived and worked in Dresden in immense austerity. The painter Wilhem von Kügelgen, son of the aforementioned Marie Helene and the painter Gerhard von Kügelgen, described Friedrich’s studio in 1813 as follows: “there was nothing there but an easel, a chair and a table (…) even the paint box had been banished to an adjoining room, as Friedrich was of the opinion that external objects impaired the view of the inner world“. For his part, the aforementioned David d’Angers described his visit to the painter’s studio in a similar way: “Friedrich led us into his studio: a small table, a bed that looked more like a coffin, an empty easel, that was all….”.

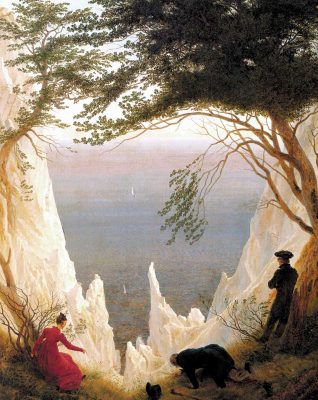

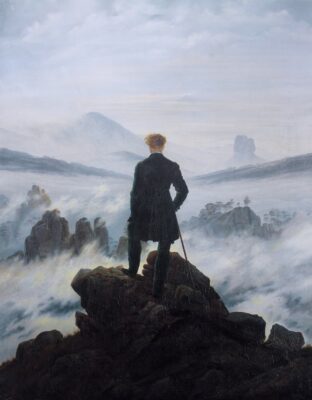

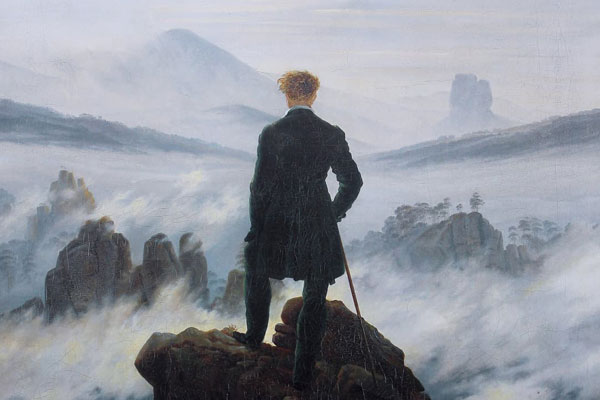

A series of trips to the Baltic in 1815 and 1816 allowed Friedrich to paint several interesting coastal landscapes, such as “Two Men by the Sea” (1817, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin). Two of his most famous works date from 1817 and 1818, “The Wanderer above the Mists” (Kunsthalle, Hamburg) and “Chalk Cliffs on Rügen” (Oskar Reinhart Foundation, Winterthur), perhaps the most notable examples of Friedrich’s Rückenfigur.

Caspar David Friedrich: “The Wanderer above the Mists”, 1817-18. Oil on canvas, 94.8 x 74.8 cm. Kunsthalle, Hamburg ·· Caspar David Friedrich: “Chalk Cliffs on Rügen”, 1818. Oil on canvas, 90.5 x 71 cm. Oskar Reinhart Foundation, Winterthur.

In the first half of the 1820s Friedrich produced some of his most famous paintings, such as “The Lonely Tree” (1822, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin) and “The Sea of Ice” (1823-24, Kunsthalle, Hamburg), but from the second half of the decade until his death in 1840 Friedrich’s fame and fortune suffered a clear blow, coinciding with the decline in admiration for the ideals of Romanticism. In addition, during his last years he suffered the after-effects of a stroke, which limited his ability to paint.

After his death, Friedrich was virtually forgotten, only to be revived at the turn of the century. However, after the Second World War his reputation suffered a further blow, as, like happened with the compositions of the other great figure of German Romanticism, Richard Wagner, Friedrich’s works were seen as nationalistic exaltation. But, as the critic Jonathan Jones rightly observed:

To see any of Friedrich’s paintings as simply nationalist is, however, mistaken. His paintings are not celebrations of German mysticism so much as examinations of it. Friedrich uses the emptiness of the Baltic shore and the Thuringian forest to suggest the hubris of empire. He is not the prophet of German territorial ambition but its satirist. Friedrich’s theme is the unconquerability of space. Human beings are tiny interlopers in a world they can never hope to rule. He exposes authority – of the monarchical states, Prussia and the rest, from which German liberals felt so alienated.

Jonathan Jones

Text: G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

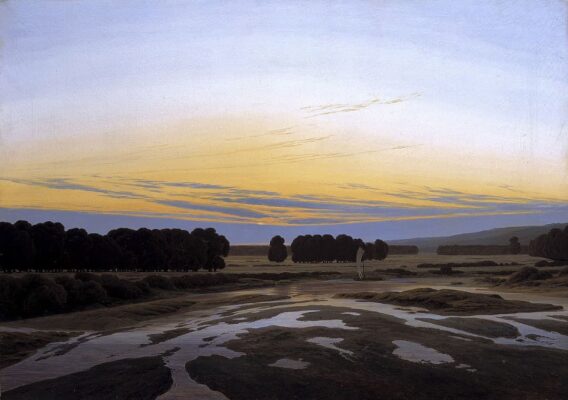

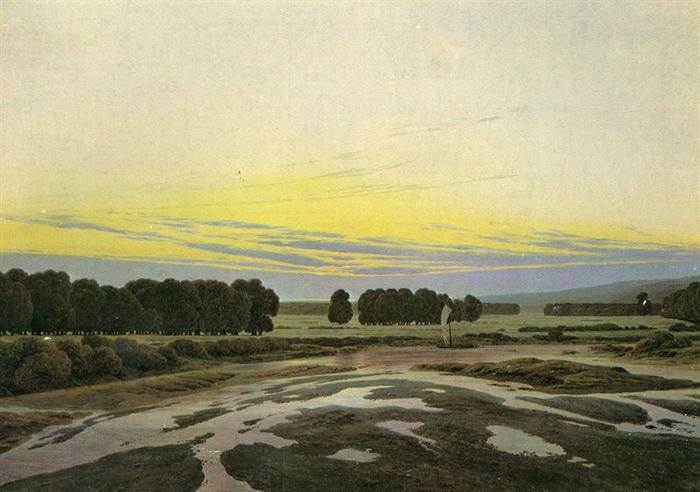

Caspar David Friedrich: “The sea of ice”, 1823-24. Oil on canvas, 96.7 × 126.9 cm. Kunsthalle, Hamburg ·· Caspar David Friedrich: “Das große Gehege (Ostra-Gehege)”, c.1832. Oil on canvas, 73.5 x 102.5 cm. Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden.

More about Caspar David Friedrich

Follow us on: