Paul Cézanne – Biography

Allow me to repeat what I said when you were here: deal with nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere and the cone, all placed in perspective, so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point. Lines parallel to the horizon give breadth, a section of nature, or if you prefer, of the spectacle spread before our eyes by the ‘Pater Omnipotens Aeterne Deus’.

Paul Cézanne, to Èmile Bernard

“Cezanne is the father of us all.” This lapidary phrase has been attributed to both Picasso and Matisse, and certainly it doesn’t matter who actually said it, because in any case it is true. While he exhibited with the Impressionist painters, Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) left behind the whole group to develop a style of painting never seen so far, which opened the door for the arrival of Cubism and the rest of the vanguards of the twentieth century.

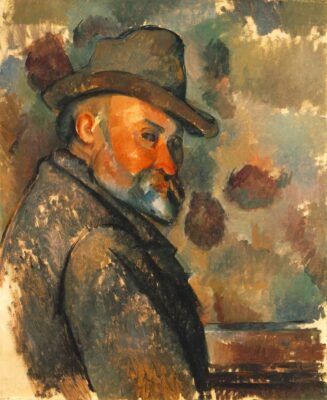

Paul Cézanne: “Self portrait”, 1875. Oil on canvas. Bridgestone Museum of Art

At a time of great innovators such as Gauguin, Munch and Van Gogh, Paul Cézanne -a solitary, obstinate and non-conformist artist- stood out above them all, and his quest for a new representational language would initiate a pictorial revolution that would finally overcome the Cartesian space present since the Renaissance. In short, to consider Cézanne as the father of modern painting is, as Felicitas Tobien wrote, “simply an act of justice“.

Paul Cézanne was born on January 19, 1839 in Aix-en-Provence, in Provence, in the south of France. At the age of 13, he entered the Collège Cézanne Bourbon, where he became friends with the future writer Émile Zola. Encouraged by Zola, he decided to become an artist and moved to Paris in 1861. Already in Paris, Cézanne met Camille Pissarro, known as “the father of impressionism”. Cézanne’s works were exhibited at the first Salon des Refusées show in 1863, which exhibited works not accepted by the official jury of the Paris Salon. Cézanne was influenced by the Impressionist painters, but by then he was already developing a personal style of painting.

In 1870, Cézanne and his mistress, Marie-Hortense Fiquet, left Paris and moved to L’Estaque, a small town near Marseille. Two years later, they moved to Auvers in Val-d’Oise near Paris. He often painted with Pissarro, referring to him as “God the Father”. Cézanne’s paintings from the early 1870s show a clear influence of Impressionism, as can be seen in “The Hanged Man’s house in Auvers“, even exhibiting at the First and Third Impressionist Exhibitions.

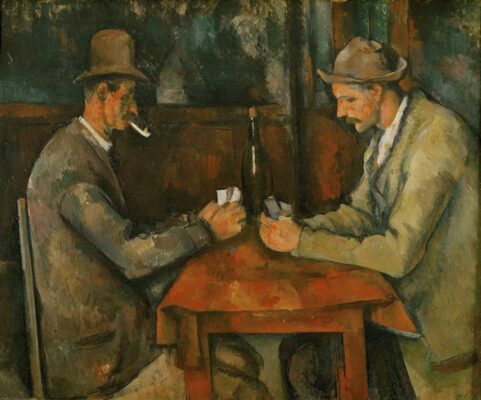

Paul Cézanne: “The hanged man’s house in Auvers”, 1873. Oil on canvas. Paris, Musèe d’Orsay. Paul Cézanne: “The card players”, 1893-96. Oil on canvas. Paris,Musèe d’Orsay.

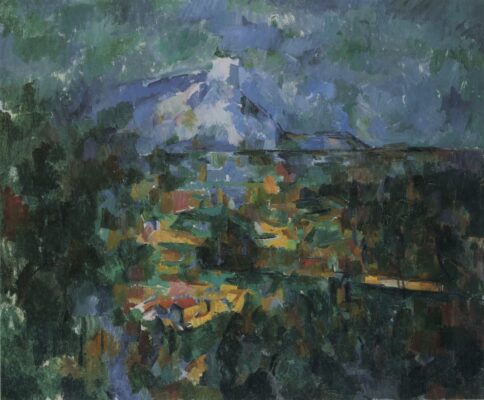

Disenchanted with the Impressionist movement, Cézanne left Paris in 1880 and established his residence in Provence. In 1886, he finally married Marie-Hortense Fiquet. That year, Cézanne’s father died, so the artist and his family moved to the former manor, Jas de Bouffan, in 1888. During the 1880s, Cézanne definitively abandoned Impressionism to develop his own pre-Cubist style, with figures often reduced to simple geometric shapes. This evolution in his style is easily noticeable in his series of paintings of “La Montagne Sainte Victoire“, in which the first paintings show a style clearly influenced by impressionism, but the last works, often unfinished, clearly anticipate the cubism of Picasso and Braque. In this later views, the triangular mountain and the elements of the meadow -both geographic and built- acquire volume not through perspective, but through the superimposition of chromatic planes.

Cézanne continued to work on his views of the Montagne Sainte Victoire for the rest of his life, but this did not prevent him from beginning another of his most important series of paintings during the following decade: The Card Players, of which there are five versions, three of which (those showing only two players, including one that was sold to Qatar for more than $250 million in 2011, then an all-time record for a work of art) can be considered the definitive ones. In these works, “Cézanne’s technique somehow equalizes and neutralizes all subject-matter (…) Cézanne’s direct way of recording visual experience broke with his own cultural prejudices, obviating numerous cultural hierarchies and the usual order of knowledge. This is what had constituted “pure painting” for those sympathetic to the notion at the beginning of the twentieth century” (Nancy Ireson and Barnaby Wright, “Cézanne’s Card Players”, 2010). Several of the experiments with spatial representation present in “The Card Players” are also visible in many of Cézanne’s still lifes, a genre in which the artist was perhaps the most important innovator.

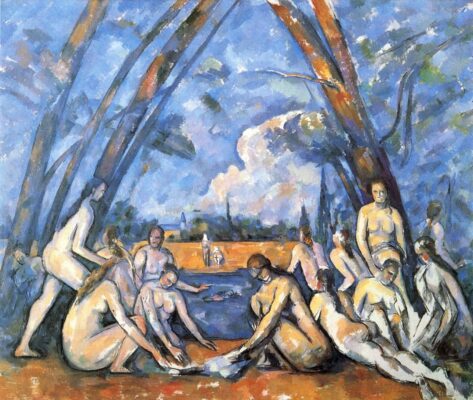

Paul Cézanne: “La Montagne Sainte Victoire, vue del Lauves”, 1873. Oil on canvas. Paris, Musèe d’Orsay. Paul Cézanne: “The Great bathers”, 1893-96. Oil on canvas. Philadelphia Museum of Art

Cézanne kept his residence until the end of his life, but he often traveled to Paris. Thanks to the Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard, the artist had his first solo exhibition in 1895. During the last years of his life he completed the three versions of “The Large Bathers“, monumental works that might have served as inspiration for Pablo Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon“. These works “are to Cézanne what ‘The Golden Age’ had been to Ingres, or ‘The Island of the Grande Jatte’ to Seurat: the synthesis of formal and conceptual harmony” (Manuel García Guatas, “Paul Cézanne”, 1993). On October 22, 1906, Cézanne died of pneumonia and was buried in the old cemetery of Aix-en-Provence.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

More about Cezanne

Follow us on: