Romanticism

A rapture that thrilled Europe

Romantic art is the fuel and the spark plug of a man’s soul. Its task is to set a soul on fire and never let it go out.

Ayn Rand

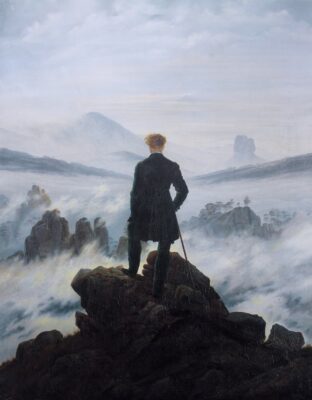

Images: Caspar David Friedrich: “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog”, 1818. Oil on canvas, Kunsthalle Hamburg ·· Eugène Delacroix: “Liberty Leading the People”, 1830. Oil on canvas. Paris, Louvre

There is no doubt that, of all the styles, periods or movements that make up the history of art, few have attracted as much interest as Romanticism, to the point that the term has transcended its definition as an artistic style to be applied to ideas, concepts or attitudes that extend far beyond the theoretical and temporal framework encompassed by the original definition of the Romantic period.

Romanticism is generally considered to be the artistic style that spread throughout Europe and the United States during the first half of the 19th century, its main characteristic being the emphasis on emotion and subjectivity as opposed to the order and reason defended by the preceding Neoclassicism, follower of the ideas of the Enlightenment. On the other hand, the Romantic movement, as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, glorified the past (in this case the medieval period, as opposed to the admiration of the classical world present in the Renaissance and Neoclassicism), nature and individuality.

During the movement’s heyday, the ideas of Romanticism were predominant in the visual arts, music and literature, while also showing influence in fields such as science and politics. In the latter, Romanticism, with its glorification of the past, is generally associated with the (re)emergence of nationalism. In the words of Enrique Valdearcos, “the artificial cosmopolitanism of the ‘Age of Enlightenment’ was succeeded by a vigorous, authentic national sentiment (…) Nostalgia for what had been lost, for the fresh and pure spirituality of the Middle Ages, for its copious and joyful fantasy, for sentiment subordinating itself to reason, led to an idealisation of those centuries which Classicism called ‘dark’ and which for the Romantics are illuminated by the most vivid and warmest lights” (E. Valdearcos, “Romanticism and realism”, 2008).

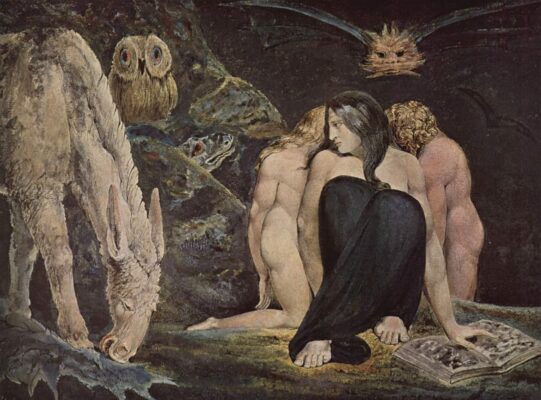

The study of the origin of Romanticism and its indirect antecedents is not easy, since the emphasis on emotion and the glorification of the past and nature already appeared in the work of artists such as Claude Lorrain (c.1600-1682) or even, in a more diffuse way, in that of late Renaissance artists such as Giorgione (1477-1510). However, the direct antecedents of Romanticism can be found in the 18th century. The Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Desire”) movement, with such prominent figures as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in literature or Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (at least in some of his compositions) in music, already sought their particular demiurge in emotion, influencing the later artists of Nordic Romanticism, such as Friedrich or Rünge. In the United Kingdom, the paintings of Henry Fuseli (Johann Heinrich Füssli) inspired William Blake, painter, poet, and one of the most fascinating figures in the history of art, whose work, however, was not widely accepted during his lifetime.

Origins of Romanticism: Henry Fuseli, “The Nightmare”, 1781. Oil on canvas. Detroit Institute of Arts ·· William Blake, “The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy”, 1795. Watercolour. Tate Britain, London.

In Germany and northern Europe, the direct heir to the Sturm und Drang movement in the visual arts was Caspar David Friedrich, the great standard-bearer of Nordic Romanticism. Both for his work -emotional and suggestive, which, although purely Romantic, seems to anticipate Symbolism- and for his personality -solitary and almost misanthropic- Friedrich is the archetype of the Romantic artist, even though his work was forgotten for decades after his death. Another artist worth mentioning is Philipp Otto Runge, who, despite his short life, made great contributions to colour theory in painting. Although this page is devoted to the visual arts, the importance of Romantic music in Germany cannot go unmentioned, with colossal figures such as Ludwig van Beethoven and Frédéric Chopin.

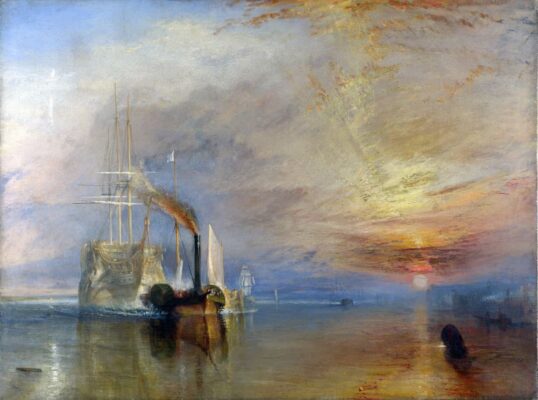

In the United Kingdom, the two great protagonists of the post-Blake Romantic era are the two somewhat opposing figures of John Constable and Joseph Mallord William Turner. While the former was the painter of rural England whose celebration of the simple life in the English countryside inspired the Impressionists, Turner was a more ambitious artist who travelled all over Europe in search of landscapes and atmospheres and whose art evolved into a style that seems to anticipate abstraction.

French Romanticism was strongly influenced by the events of the French Revolution and the political turmoil that followed. Théodore Géricault‘s famous “The Raft of the Medusa” (1818-19) is a strong anti-government critique, clearly Romantic in spirit, although the formal echoes of Neoclassicism are still discernible. The great figure of Romanticism in France is Eugène Delacroix, whose “Liberty Leading the People” (1830), wrongly associated with the French Revolution, has become possibly the most representative image of Romanticism, demonstrating the power of painting to become the symbol of an era.

Sculpture was little worked on by the artists of Romanticism, who preferred the spontaneity and freedom of painting or drawing. Among the most important sculptors of this period were the French artists Auguste Préault and François Rude. In architecture, admiration for the medieval period gave way to a revival of Gothic formal values, giving rise to the Neo-Gothic movement, which has already been discussed -along with the other revivals– in the chapter devoted to Neoclassicism. However, the great Romantic contribution to architecture came in the treatment of outdoor space, with the landscape architecture developed in England.

Romanticism in Europe: Joseph Mallord William Turner, “The Fighting ‘Temeraire’”, 1838. Oil on canvas. National Gallery, London ·· Francisco de Goya: “The Third of May 1808 in Madrid”, 1814. Oil on canvas. Museo del Prado, Madrid

In Spain, the work of Francisco de Goya (especially his Black Paintings and his monumental depictions of the French invasion of Madrid) have traditionally been associated with Romanticism, although the Spanish painter cannot be categorised categorically within the movement. It seems more appropriate to consider Goya, like the aforementioned William Blake, as belonging to a category of unique artists who are difficult, almost impossible, to classify. In Italy, the leading figure was Francesco Hayez, author of the famous “The Kiss” (1859). On the other hand, it is difficult to speak of Romanticism in Russia, where the values of the movement arrived late and are often mixed with those of Symbolism or Realism. The work of Ivan Aivazovsky, author of the sensational “The Ninth Wave” (1850), can generally be classified as Romantic, albeit with a strong Realist influence.

In the United States, Romantic art found its greatest expression in the landscapes painted by the artists of the Hudson River School, to which we have devoted a more detailed study in theartwolf.com. In this brief essay on Romanticism, we shall content ourselves with highlighting figures such as Thomas Cole and Asher Brown Durand as part of the first generation, and Frederic Edwin Church as the leading figure of the second generation, as well as the figure of Albert Bierstadt in the American West.

Romanticism in Russia: Ivan Aivazovsky, “The Ninth Wave”, 1850. Oil on canvas. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg ·· Romanticism in America: Asher Brown Durand, “Kindred Spirits“, 1849. Oil on canvas. Crystal Bridges Museum of Art.

Romanticism began to lose influence in the mid-19th century, giving way to trends such as realism in the arts and positivism in philosophy. But Romanticism, which “burst in with true revolutionary overtones; passed quickly and nothing was ever the same again” (José Luis Yepes Hita, “Los orígenes filosóficos del Romanticismo”, 2012) profoundly marked the evolution of later Western art, and its values can be observed in many artistic movements of the 20th and 21st centuries, from the surrealism of the 1920s and 1930s and the “New Romantic” current of the 1970s, to the images and scenarios created in digital art in the 21st century.

Text: G. Fernandez · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: