Impressionism

The rejects who changed the history of Art

The common view that brings these artists together in a group and makes of them a collective force within our disintegrating age is their determination not to aim for perfection, but to be satisfied with a certain general aspect. Once the impression is captured, they declare their role finished. (…) If one wishes to characterize and explain them with a single word, then one would have to coin the word impressionists. They are impressionists in the sense that they paint not landscapes but rather the sensation produced by the landscape. The word itself [impression] has entered their vocabulary; it is not a landscape but instead an impression that one calls the ‘Sunrise’ by Mr. Monet.

J. Castagnary, April 29th 1874

Images: Claude Monet: “Impression, sunrise”, 1872. Oil on canvas, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris ·· Édouard Manet: “The Railway”, 1873. Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

In nineteenth-century Paris, the great goal of any painter who aspired to make a living from his art was to exhibit at the Paris Salon, the great annual event of the Académie des Beaux-Arts which, since the end of the seventeenth century, presented the works of the most important artists to the wealthiest collectors. But by the 1860s, at the dawn of the Belle Epoque, the elitism and self-indulgence of the jury had reached unbearable extremes as any work that departed even slightly from the designs of the Académie was immediately ignored and even ridiculed. At the 1863 edition, two thirds of the works submitted to the Salon were rejected, which led Napoleon III -whose tastes were not exactly “progressive”- to decide to give the artists rejected by the Académie a place to exhibit, in an annexe to the official Salon. There, in that unglamorous annexe that was somewhat derogatorily called the “Salon des Refusés” (Salon of the Rejected), the history of art was changed forever.

The Salon des Refusés included Gustave Courbet -who in the past had exhibited some works at the official Salon, but whose honest, realistic painting was no longer to the jury’s liking- together with a number of young painters, including Édouard Manet, who presented his “Le déjeuner sur l’herbe”, as well as Paul Cézanne and Camille Pissarro. Although the reception of the works was generally negative, the exhibition opened the way for these “dissident” painters to come into contact with each other, exchanging techniques and ideas, and initiating the Impressionist movement, sometimes considered the starting point of modern art.

From a technical point of view, Impressionism is characterised by its loose brushstrokes, using pure colours obtained thanks to the appearance of new pigments to be used in oil painting. Rather than a precise representation of the model (person, object or landscape), the aim was to capture the effect of light and atmosphere on it, often painting outdoors. For all these reasons, although “Impressionist sculpture” or even “Impressionist music” are terms often used to describe the art of figures like Auguste Rodin or Claude Debussy, Impressionism is an eminently pictorial style, with its epicentre in France, although it quickly spread to other parts of Europe and the United States.

Impressionism borrowed from the realism of Courbet and the Barbizon School a taste for “ordinary” subjects and landscapes, far removed from the exoticism or mythology of Academicism and Neoclassicism In addition to experimentation with the effects of light on the same model, its great thematic innovation was the interest in modern life, making Haussmann’s new Paris -with its bustling avenues, iron bridges, and modern railway stations- the favourite setting for the young Impressionist painters.

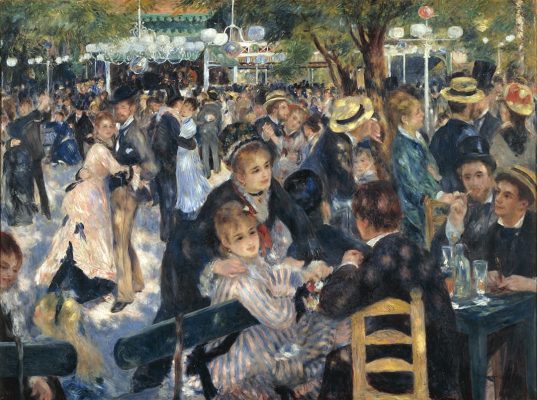

Images: Pierre-Auguste Renoir: “Bal du moulin de la Galette“, 1876. Oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris ·· Gustave Caillebotte: “Rue de Paris, temps de pluie”, 1877. Oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago.

The protagonists

Édouard Manet (1832-1883): sometimes considered “the father of Impressionism”, although he never considered himself to be part of the group. With his “Le déjeuner sur l’herbe” -presented, as mentioned above, at the Salon des Refusés in 1863- and his “Olympia”, painted in the same year, Manet rebelled against the canons of academic painting, encouraging a group of young painters to seek new paths in painting, which later led to the emergence of the Impressionist movement.

Claude Monet (1840-1926): the Impressionist painter par excellence, a prolific genius who created more than 2,500 works, and author of series of paintings -such as his “haystacks” or “water lilies”– in which he studies the effects of changing light on a single object, experiments that are indispensable for understanding the genesis of modern art.

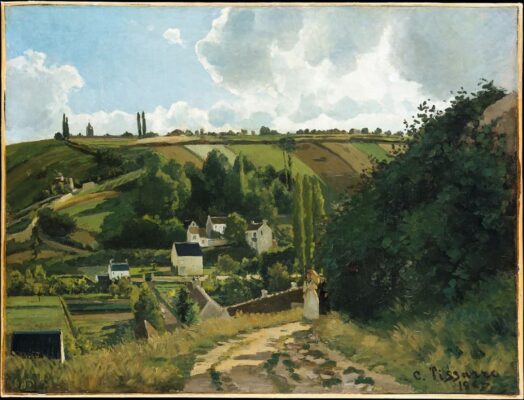

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903): described by Paul Cézanne as “the first Impressionist”, Pissarro was particularly interested in landscapes, both in rural France (Eragny, Louveciennes) and on the Parisian boulevards.

Pierre Auguste-Renoir (1841-1919): among all the painters of the Impressionist group, Pierre-Auguste Renoir was possibly the most prolific, the most focused on classical themes as opposed to the modernity of iron bridges or train stations, and the one with the most disconcerting career, as he soon abandoned Impressionism in favour of a more classical style.

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895): the most important of all the French Impressionist painters, she became -despite having exhibited in the official Salon for almost a decade- a staunch supporter of Impressionism, exhibiting in seven of the Impressionist Exhibitions.

Alfred Sisley (1839-1899): the son of English merchants, Sisley focused almost exclusively on landscape painting, and was one of the few painters who never abandoned the Impressionist style.

Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894): to the relevance of his pictorial oeuvre, highly important although perhaps not at the same level than the famous painters mentioned before, Caillebotte was also a vital patron of the arts, thanks to his wealthy social status, helping the other Impressionist painters to overcome their financial difficulties.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917): Degas was never a “pure” Impressionist (he himself rejected the term), but his style and even his fame during his lifetime contributed to the recognition of the Impressionist movement.

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917): sometimes considered “the father of modern sculpture”, Rodin was not strictly an Impressionist (we have already indicated that Impressionism is basically a pictorial movement), but ” his interest in the effect of light on sculpted surfaces, and the experimental nature of his methods reveal the extent to which Impressionism influenced his sculpture.” (Eva Sarah Molcard, “21 Facts About Auguste Rodin”, 2018)

Within France, other important names include Frédéric Bazille, Eva Gonzalez, Armand Guillaumin and Marie Bracquemond. Figures such as Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin are sometimes associated with Impressionism, and had contact with the movement during their youth, but soon abandoned the Impressionist style. In the United States, American Impressionism was led by Mary Cassatt, who worked for years with the French Impressionists, and other figures such as Theodore Robinson and Childe Hassam.

Images: Alfred Sisley: “L’Inondation à Port-Marly”, 1876. Oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, paris·· Berthe Morisot: “Jour d’eté”, 1878. Oil on canvas , National Gallery, London.

A brief history of Impressionism

Background

On the basis of the technical characteristics of Impressionism -discussed above- a multitude of possible “origins” or “antecedents” for Impressionism have been proposed, some with more foundation than others. The loose brushwork of Frans Hals (1582-1666) seems a proven influence, as confirmed by critics such as Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. (“Frans Hals, Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century“). Both J.M.W. Turner’s”atmospheric” painting and John Constable‘s interest in rural and everyday landscape (as well as his plein air painting technique) were also an influence on several Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters, who were able to admire their work in London.

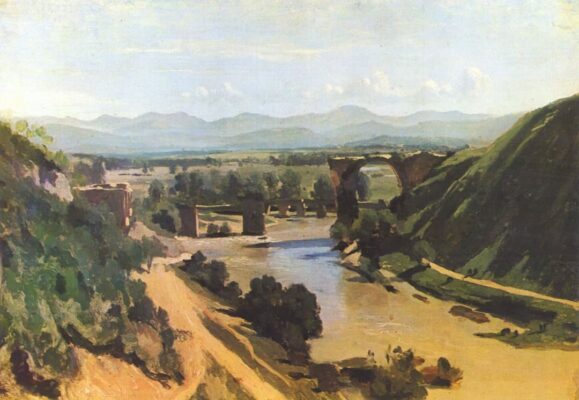

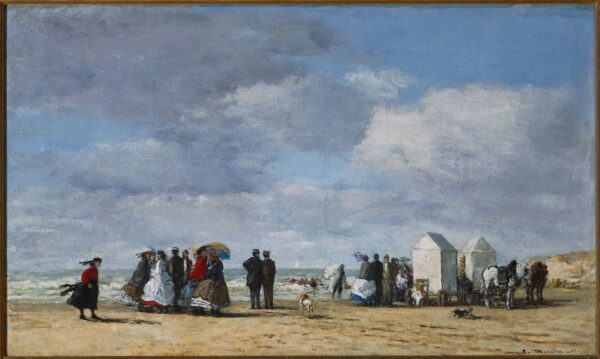

The clearest influences on Impressionism came from 19th-century French realism, notably the landscapes of Camille Corot, who personally knew some of the Impressionist painters, such as Berthe Morisot. “Instead of analysing a feature, one feels an impression,” wrote the critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger of Corot’s landscapes in 1868, six years before the famous exhibition at which the Impressionist movement was given its name. The landscapes of Eugène Boudin (1824-1898) and Johann-Barthold Jongkind (1819-1891) are another direct influence, to the extent that these two painters are sometimes considered “proto-Impressionists”.

Background to Impressionism: Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: “Le pont de Narn”, 1826. Oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris ·· Eugène Louis Boudin: “The Beach at Trouville”, 1865. Oil on canvas, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton.

The beginnings

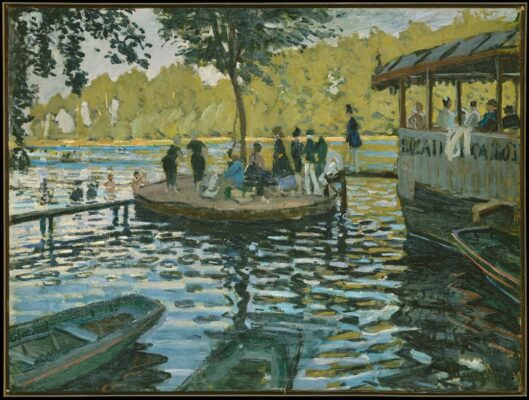

After the exhibition of Édouard Manet‘s “Le déjeuner sur l’herbe” at the “Salon des Refusés” in 1863, mentioned above, as well as his equally important “Music in the Tuileries” painted the same year, the seed of Impressionism was planted, but the full Impressionist style would not develop until the end of the decade. In 1867, Claude Monet painted “Terrasse à Sainte-Adresse“, in which he took a further step in the plein-air Impressionist technique sketched by Manet in his paintings of 1863. That same year, Camille Pissarro painted “La Colline de Jalais, Pontoise“, in which the influence of Corot is still appreciable behind its almost fully Impressionist style. From the following year is Monet’s “The Magpie (La Pie)“, which the Musée d’Orsay describes as “the work in which the Impressionist landscape was born, five years before the first official exhibition in which the movement received its name“. The birth of Impressionism can be considered complete in 1869, when Monet painted his views of “La Grenouillère“.

During these formative years, the Impressionist painters received much misunderstanding and very little support. Among the supporters was the writer Émile Zola, Paul Cézanne’s friend and schoolmate, and the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. The latter had met some of the Impressionists in London, where they had fled during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and exhibited 139 paintings at the Society of French Artists in London, including two by Monet and two by Pisarro, which had previously been rejected by the Royal Academy (Bernard Denvir: “Chronicle of Impressionism“, 1993). On his return to France, he continued purchasing Impressionist works, and would later be the first dealer to organize an Impressionist exhibition in the United States.

The beginnings of Impressionism: Camille Pissarro: ” La Colline de Jalais à Pontoise”, 1867. Oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris ·· Claude Monet: “Bain à la Grenouillère”, 1869. Oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum, New York.

The maturity

In 1874 the First Impressionist Exhibition took place, which featured 165 works including Pierre-Auguste Renoir‘s “La Loge” (1874), which was offered for 500 francs (not sold), Paul Cézanne‘s “The House of the Hanged Man” (1873) for 300 francs (sold), and Claude Monet‘s “Impression, Sunrise” (1872) for 800 francs. It was precisely a mocking criticism of this painting by the critic Louis Leroy that gave the movement the name “Impressionism”.

The First Impressionist Exhibition was followed by seven more exhibitions between 1876 and 1886, with mixed fortunes in terms of sales and critical acclaim. In particular, the ambitious Third Impressionist Exhibition, which included many works now considered icons of the movement, such as “Dance at the Moulin de la Galette” (1876) by Renoir, “Paris, Rainy Day” (1877) by Gustave Caillebotte, or “The St. Lazare Station” (1877) by Monet, was a financial failure, which improved somewhat at the next exhibition (1879), but failed to gain critical support. In addition, the two major auctions of Impressionist art held at the Hôtel Drouot in 1878 were well below expectations.

It could be said that at the end of the 1870s Impressionism continued to exist as a more or less cohesive movement (thanks in part to the support of Paul Durand-Ruel and Gustave Caillebotte), but many of the artists who formed it were beginning to feel disenchanted with the movement, and during the following decade, several of them broke away from it, even though in many cases they continued to show their works at the Impressionist Exhibitions.

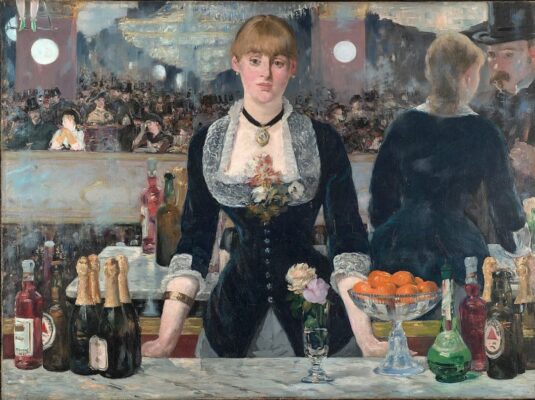

Images: Claude Monet: “La Gare Saint-Lazare”, 1877 Oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris ·· Édouard Manet: “Un bar aux Folies Bergère”, 1882 Oil on canvas, Courtauld Gallery, London.

Taking different paths: Late Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

In the early 1880s, the defections within the Impressionist group were notable. Cézanne left Paris and moved to Provence, attracted by the local landscape, where he developed his proto-Cubist style that would eventually become indispensable for understanding the avant-garde. Renoir destroyed several of his earlier canvases and returned to a more classical style, inspired by the works of Ingres. Even those painters most faithful to Impressionism were not unaffected by this wave of change. Pissarro, for example, from the mid-1880s onwards adopted a neo-Impressionist style inspired by the Pointillism of Seurat and Signac. Claude Monet, for his part, remained the standard-bearer of Impressionism, but he increasingly distanced himself from his peers, to the extent that “Pissarro and Degas, as well as Félix Fénéon -the spokesman for the Neo-Impressionists- criticised Monet’s new creations as superficially decorative” (Karin Sagner-Düchting: “Claude Monet”, 1990).

The “decline” (in many cases, transformation into a post-Impressionism even bolder and more innovative than the style from which it derived) of Impressionism in France (and by extension, in Europe) coincided with the rise of American Impressionism, led by the figure of Mary Cassatt, who had painted for years in France, meeting the leading Impressionist painters and becoming a personal friend of Berthe Morisot. Cassatt and Theodore Robinson were perhaps the only “pure” Impressionists in the United States, while artists such as Childe Hassam and John Henry Twachtman showed influences from other American styles, such as Tonalism.

Impressionism in the United States: Mary Cassatt: “Summer”, 1894. Oil on canvas, Terra Foundation for American Art ·· The influence of Impressionism on sculpture: Auguste Rodin: “Les Bourgeois de Calais”, 1884. Bronze, Musée Rodin, Paris. Photograph by LPLT / Wikimedia Commons.

The legacy of Impressionism

Impressionism, which as mentioned above was largely ridiculed in its early days, experienced from the last decade of the 19th century onwards an enormous increase in acceptance and popularity. As early as 1895, Claude Monet was selling each of his canvases from the “Haystacks” and “Rouen Cathedral” series for prices of up to 15,000 francs each, and works by artists such as Degas and the late Manet were being avidly collected in both Europe and the United States. The definitive acceptance came in 1907, when the Impressionists’ works entered the most important museums in Europe and in the United States, with the Louvre hanging Manet’s “Olympia” in its galleries, and the Metropolitan Museum paying the extraordinary sum of 84,000 francs for Renoir’s “Madame Charpentier and Her Daughters“.

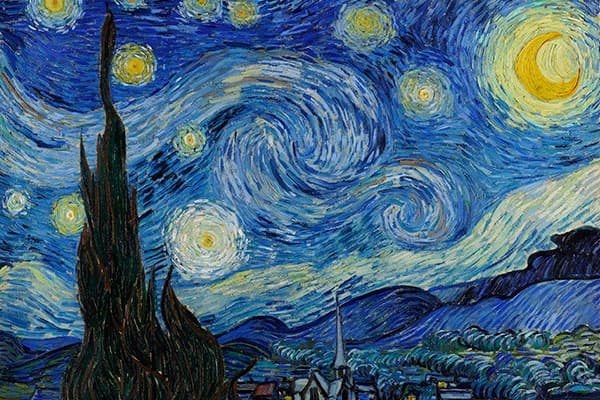

In the following decades, Impressionism would gain prestige among critics and admiration among collectors, to the extent that the value of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings would reach or even surpass that of Old Master paintings. In 1967, Monet’s aforementioned “Terrasse à Sainte-Adresse” was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum for $1.4 million, a price only achieved at that time by masterpieces by painters such as Leonardo and Rembrandt. The definitive consecration would come with the boom of the 1980s and early 1990s, when works by Van Gogh and Renoir were sold for the highest prices ever paid for a work of art.

Text: G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: