Symbolism

Elusive evocations

I am lovely, O mortals, like a dream of stone,

Charles Baudelaire. “The Flowers of Evil” (XVII: Beauty)

And my bosom, where each one gets bruised in turn,

To inspire the love of a poet is prone,

Like matter eternally silent and stern

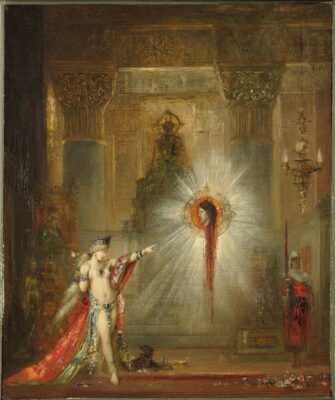

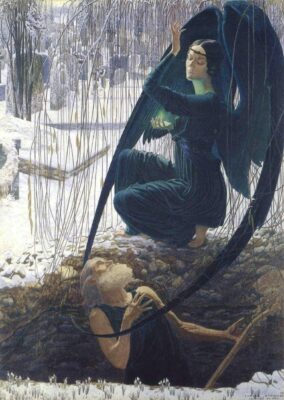

Images: Gustave Moreau “The Apparition (Head of St. John the Baptist)”, 1876-77. Oil on canvas. Fogg Museum ·· Carlos Schwabe: “Death of the Gravedigger“, 1895. Oil on canvas. Paris, Louvre.

Of all the artistic movements in 19th-century Western art, Symbolism is probably the least known and, although it would not be correct to describe it as “little studied” (fortunately, there is now an abundance of literature on any artistic period or style), it could be considered the least researched. It is still possible to find texts that refer to Symbolism as “late Romanticism”, despite the fact that both movements, beyond some formal coincidences, are appreciably different. Much of the blame for this “lack of popularity” of Symbolism within the study of 19th century visual art may be due to the fact that it is primarily a literary movement (its starting point is generally considered to be the publication of Charles Baudelaire‘s “The Flowers of Evil” in 1857), but it seems even more accurate to point to the fact that Symbolism developed at the same time as Impressionism, whose fame and recognition has obscured the importance of Symbolism.

And yet, for anyone interested in modern art, Symbolism should be fascinating. It experiments with the power of art as a transmitter of the artist’s inner world as the most daring of the avant-garde, decades before Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism came on the scene. In Symbolist painting, the elements represented in the painting acquire, through synthesis and composition, a meaning that goes beyond that which could be attributed to them separately, just as Baudelaire’s poetry sought to decipher the “forest of symbols”, establishing correspondences between letters and colours, words and perfumes. It does not constitute, like Romanticism, a subjective and suggestive vision of reality, but constructs its own reality. “The synthesis, by combining elements from the real world with those taken even from the other arts, will succeed in creating a different and self-sufficient reality” (Aurora Fernández Polanco, “Fin de siglo: Simbolismo y Art Noveau”, 1989).

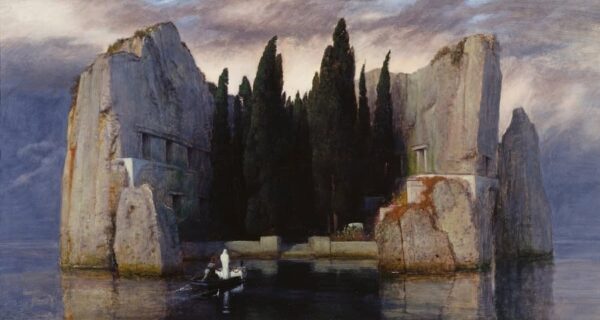

Images: Odilon Redon “Reflections”, 1900-05. Pastel on paper. Private collection ·· Arnold Böcklin: “The Island of the Dead (third version)”, 1883. Oil on canvas. Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

Perhaps by its very nature, Symbolism was not an organised movement, but rather a group of artists working individually, sometimes unrelated to each other. There is indeed a Symbolist Manifesto, signed by Jean Moréas in 1885, but it came years after the great Symbolist painters had defined their personal style. Among them was Gustave Moreau (1826-1898), creator of the famous “The Apparition” (perhaps the most famous image of Symbolism), and whose art was described by Pierre Courthion as “overloaded with opal columns and chrysoberyl walls (…), the exact opposite of Courbet’s realism and anti-intellectualism” (Historia del Arte, Salvat Editores, Volume 9, chapter 2, “Symbolism and ‘nabis'”, 1984). Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898), admired by Émile Zola, adopted a seemingly more “realistic” aesthetic than Moreau. The third great representative of Symbolism in France was Odilon Redon (1840-1915), whose brightly coloured, dreamlike art seems to anticipate several 20th century avant-garde movements, such as Fauvism and Surrealism. In addition to the three artists mentioned above, several names commonly associated with Post-Impressionism have been linked to a greater or lesser extent to Symbolism. The most important of these is Paul Gauguin, whose free use of colour influenced the group of painters known as “Nabis“, especially Paul Sérusier and Maurice Denis.

Symbolism had important followers in Belgium, notably Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921), who exhibited at the Salons de la Rose+Croix organised in Paris in the 1890s by the occultist Joséphin Péladan, which served to publicise the work of several second-generation Symbolists. The most prominent figure of Symbolism in central Europe was the Swiss Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901), creator of the five versions of “The Island of the Dead“. Charles Schwabe (1866-1926), author of the famous “Death of the Gravedigger“, also exhibited at the Salons de la Rose+Croix. Franz von Stuck (1863-1928) is often considered to be part of the Art Nouveau, but he always retained a symbolist background, as can be seen in his famous painting of “The Sin“, of which he produced several versions.

Text: G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: