An art market milestone: Paul G. Allen Collection fetches $1.5 billion at Christie’s

By G. Fernández · theartwolf.com · Texts referring to the auction preview written on 24 and 25 October 2022 · Updated on 09/11/2022 with the auction results.

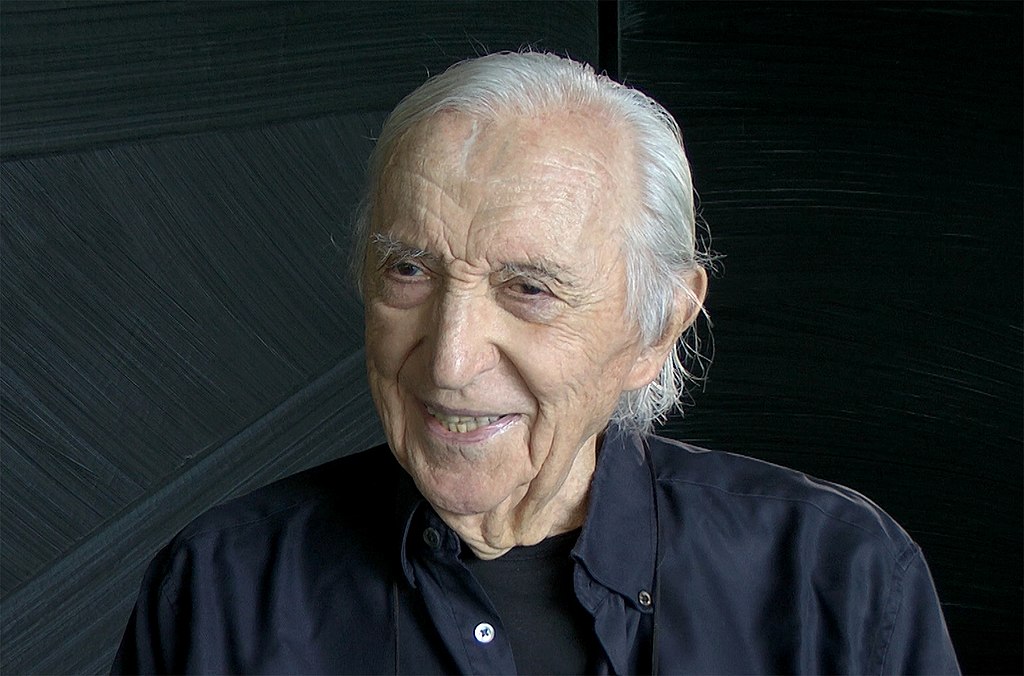

With a combined value in excess of $1 billion, and with several works potentially fetching prices in excess of $100 million, the auction of the collection of Microsoft co-founder Paul G. Allen (1953 – 2018) is set to make art market history on 9 November 2022. After presenting some previews of the works that would be included in the auction, Christie’s finally published, in the last week of October, the complete online catalogue of the auction, which, of course, is full of “blockbusters”, but which is also notable for not including several of the masterpieces that Allen acquired during his lifetime (such as a Monet bought in 2016 for more than $80 million), and which may be included in future auctions, or perhaps donated to museums. Whatever the case, the works included make it very likely to be the most valuable art auction in history, the proceeds of which, according to Paul G. Allen’s wishes, will be dedicated to philanthropy.

The auction was an immense success, fetching a total of nearly $1.5 billion, which is -as predicted- a new record for an art auction, and by a large margin. Five paintings exceeded $100 million, led by the $149.2 million paid for Seurat’s small “Les Poseuses, Ensemble“. Of particular note was the activity of Asian buyers, who possibly acquired at least three of these hundred-million-dollar paintings, including the aforementioned Seurat.

A Mount Rushmore of Post-Impressionism: Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Seurat

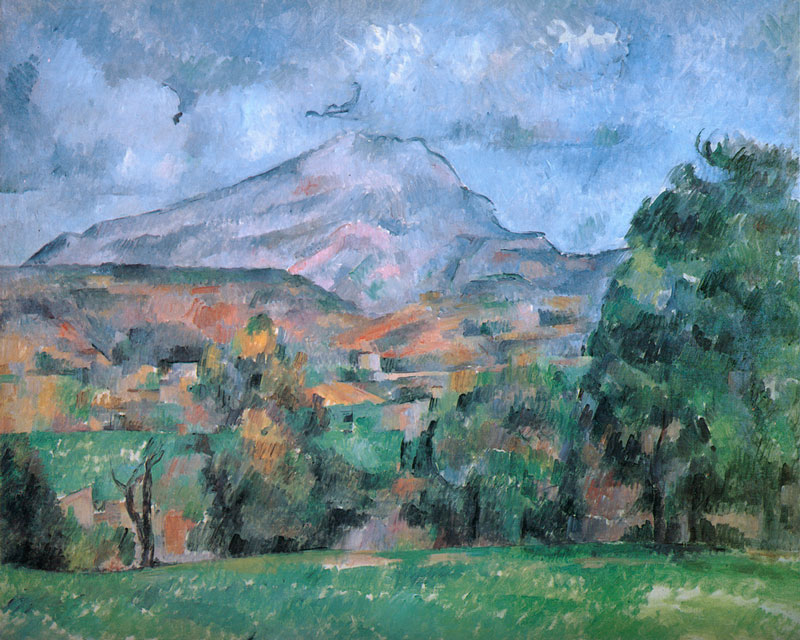

Paul Cézanne is the most important modern painter not named Pablo Picasso, and his views of the Montagne Sainte-Victoire can be considered, together with his famous “Card Players”, as his most ambitious and relevant works, being the clearest precedent of Cubism, the avant-garde that would revolutionise 20th century art. With this in mind, it seems clear that “La montagne Sainte-Victoire” is destined to emerge victorious (pardon the pun, it won’t be the only one -and possibly not the worst- in this article) from the auction. Christie’s expects the work to fetch in excess of $100 million, which would be in line with the $100 million paid some seven years ago by the Qatari state for “La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, vue du bosquet du Château Noir“. The version on sale at Christie’s is certainly a remarkable painting, though far from the almost Cubist boldness of later versions of the same subject. Interestingly, the last time this painting was sold (2001, for some $35.8 million), Scott Schaefer of the Getty Museum described it as “a B-level painting“, a description which, however, is quite exaggerated. With a starting price of $90 million (!), the work was auctioned for $137.8 million after a surprisingly quick succession of bids.

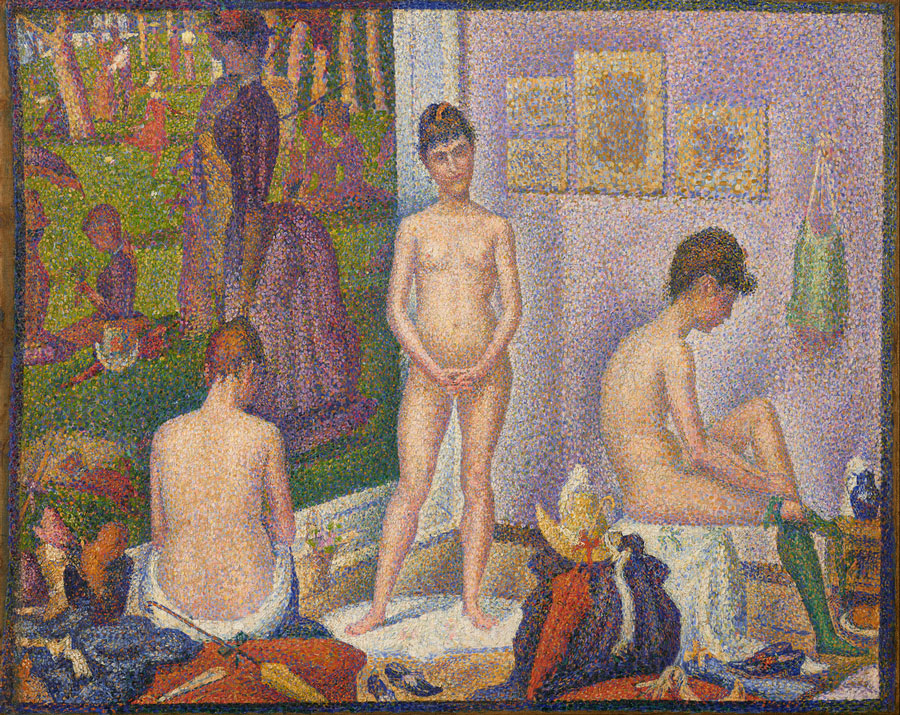

The painting that competes with the Cézanne for the unofficial title of the collection’s top star is “Les Poseuses, Ensemble”, the smaller (considerably smaller) version of Georges Seurat‘s famous work in the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. Although Seurat does not possess -at least in the art market a fame comparable to that of “Cézanne the man”, he is, of course, one of the great innovators of modern art, a painter who is “the son of nineteenth-century positivism who sought to extend scientific methods to all areas of human activity (…) and of course to the visual arts” (Manuel López Blázquez: “Seurat”, 1995). And, equally relevant to the art market, his important works very rarely appear on the market, this painting being the most important to come on the auction block since “Paysage, l’Ile de la Grande Jatte” fetched $35 million at the auction of the Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney Collection in 1999. Interestingly, at that auction the price of the Seurat was partly overshadowed by that of a work by Cézanne, which fetched $60.5 million. Precedent for this auction? It does not seem so. In favour of “Les Poseuses, Ensemble” is the fact that it is not a sketch, but a complete work, albeit much smaller in size (39.3 x 50 cm) than the famous larger version in Philadelphia. Christie’s has equalled its valuation to that of the Cézanne, and expects the painting to fetch more than $100 million. Optimistic? Possibly. Justified by the artist’s importance and the scarcity of his masterpieces in private hands? Quite so. With a starting price of $75 million, the painting was sold for an amazing $149.2 million after an endless succession of bids. The winning bid, by the way, was apparently made by an Asian (possibly Chinese) buyer. The price is obviously a record for the artist.

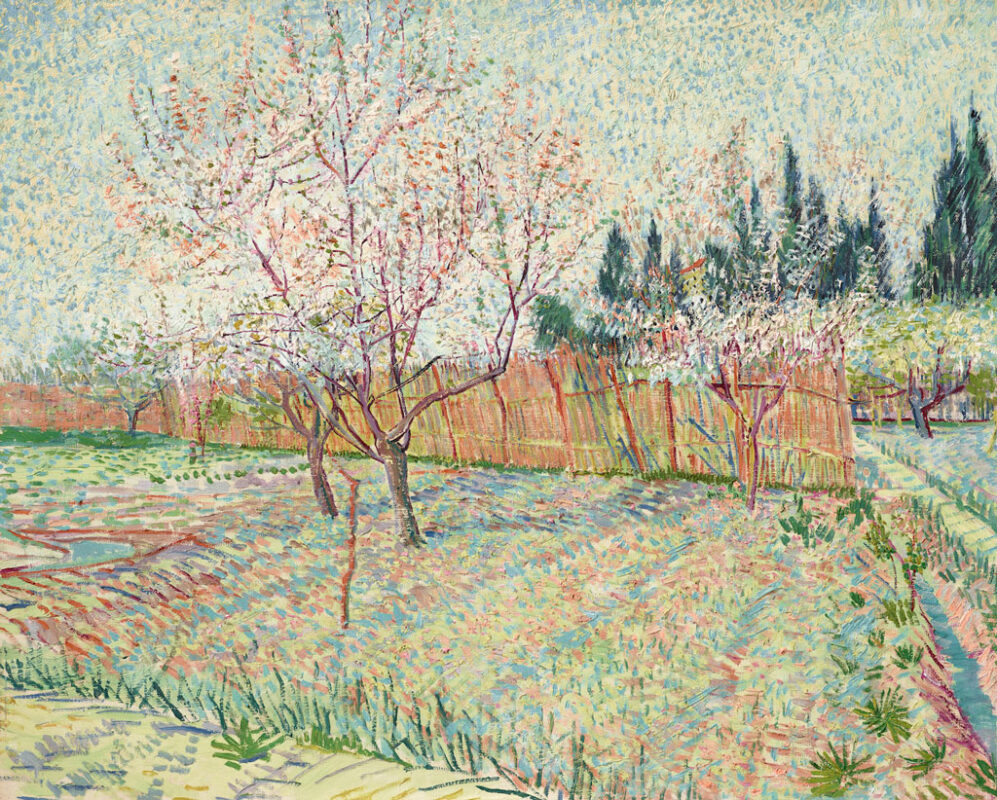

Van Gogh. Dear Vincent, what mega-art auction is complete without one of your paintings? None, and the Allen Collection has solved that problem. Painted in 1888, Vincent van Gogh‘s “Verger avec cyprès” is a true beauty, arguably the most attractive of all the Dutch superstar’s landscapes to come on the market since “Paysage sous un ciel mouvementé” (1889) was auctioned for $54 million in 2015. The painting belongs to a series of Japanese-inspired depictions of blossoming orchards painted by Van Gogh in Arles in the spring of 1888, and although it is not the only one of these paintings in private hands, it is one of the most accomplished. Ingo F. Walther, whose biography of Van Gogh is a must-read for any art lover, states that in these blossoming orchards “Baudelaire’s formula of the poetic in the historical, the eternal in the ephemeral, appears inverted. Van Gogh seeks the ephemeral in the eternal, he seeks in reality the moment that makes plausible his vision of a better life, his projection of Japan. The instant must make real what the imagination has passionately projected“. Less important than the Cézanne, less “exclusive” than the Seurat, the painting is nonetheless a really good Van Gogh, and any really good Van Gogh can fetch $100 million if the auction keeps up the right pace. With a starting price of $80 million, the Van Gogh was sold for $117.2 million, possibly also to an Asian buyer.

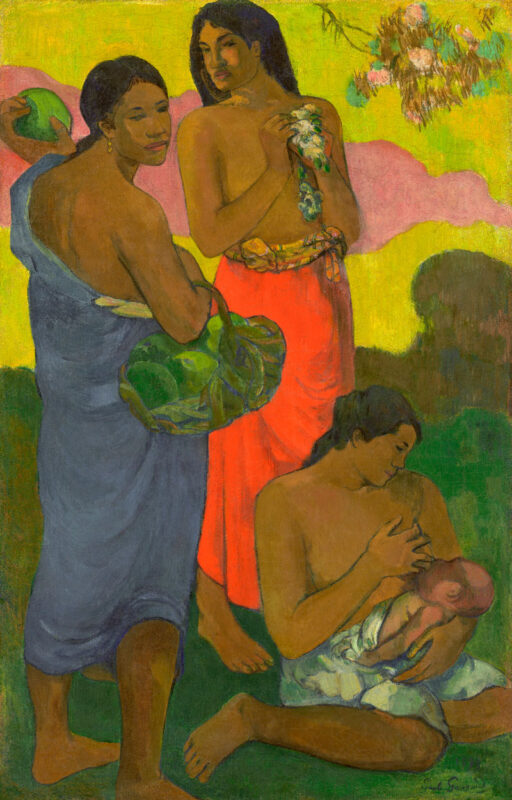

Completing the quartet of Post-Impressionist champions is Paul Gauguin, represented at auction by “Maternité II“, a painting that has passed through some of the most important modern art collections of recent decades, including those of David Rockefefeller, Barbara Piasecka Johnson and, of course, Paul Allen. The last time the painting came up for auction -in 2004- it fetched $39.2 million, below its estimate of $40-50 million. It is undoubtedly an important Gauguin, certainly not at the level of the “Nafea faa ipoipo?” that Qatar acquired for $210 million a few years ago, but it is the most important to appear at public auction since “L’homme à la hache” was auctioned for $40.3 million in 2006. Although its valuation has not been made public, some sources suggest a figure in the region of $90 million. Gauguin is an artist whose works seem very difficult to value. Let us recall, for example, the very different figures suggested for the “Mata Mua” in the Thyssen collection, or the case of “Otahi“, acquired by Dmitry Rybolovlev for $120 million, and subsequently resold for barely $50 million. With a starting price of $70 million, the work was sold for $105.7 million.

The calm Signac, the calmer Monet, the even calmer Klimt

Despite the fact that the four works mentioned above deserve to be discussed in a separate chapter because of their hefty presale estimates, they are not the only Post-Impressionist masterpieces offered at this auction. Specifically, Paul Signac‘s “Concarneau, calme du matin (Opus no. 219, larghetto)” is a pictorial marvel. The work is part of a group of five paintings known collectively as “La Mer: Les Barques (Concarneau),” of enormous importance in the artist’s career, and, carrying a presale estimate of between $28 million and $35 million, it aspires to reclaim its throne as Signac’s most expensive painting, a title it earned in 1998 when it was auctioned for $4.4 million (I remember seeing the result of the sale then in a Galerie Antiquaria magazine, where the work was presented under the title “Calme du matin, Concarneau,” which for some reason sounds more poetic). This beautiful painting sold for $39,3 million, a new auction record for Signac.

Whoever buys the Signac will be, therefore, acquiring one of the most beautiful and important works of its author. It will not be the case, in my opinion, of whoever buys “Waterloo Bridge, soleil voilé“, painted by Claude Monet between 1899 and 1903. It is, of course, a good painting, but it is nowhere near the level of other works by Monet in the Paul Allen collection that, for some reason, have not been included in the auction (“Nympheas“, “Meules“… the list and reasons for exclusion would be enough for a separate essay). This painting was auctioned in 1997 for $8.2 million, a very remarkable price for a Monet then, and although its estimate has not been published, some sources place it over $60 million, well above the comparable “Waterloo Bridge, effet de brume” (auctioned in July this year for £30 million) or “Waterloo Bridge, effet de brouillard“, (auctioned last year for $48.5 million). In this auction, “Waterloo Bridge, soleil voilé” was sold to a European buyer for $64.5 million.

The calm that exists in the Signac and Monet is elevated to an ethereal, almost mystical category in “Birch Forest” a painting that has everything you could ask of a great Gustav Klimt landscape. The painting was part of a group of four paintings by Klimt, from the collection of Adele and Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, auctioned by Christie’s in 2006. The painting then fetched $40.3 million; a price eclipsed then by the $87.9 million achieved by the second version of the portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. Some sources indicate that in this auction the painting could exceed $90 million, setting a new record (without taking into account inflation) for a work by the artist at auction, although it would be far from the prices achieved in private sales by the two versions of the portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer or the second version of “Water Serpents“. The painting was sold for $104.5 million, possibly to an Asian buyer.

The not so magnificent Magnificat

If when talking about the Seurat I noted that the almost total absence of masterpieces by the artist in private hands was an important factor in supporting the (unofficial) estimate in excess of $100 million, this factor should be raised to extreme levels in the case of Sandro Botticelli‘s “Madonna of the Magnificat“.

Sandro Botticelli is, of course, one of the great geniuses of the Italian Renaissance, with the added attraction that – contrary to what happens with authors such as Masaccio or Piero della Francesca- several of his works (“Primavera“, “The Birth of Venus“) have become part of contemporary pop culture, bringing the fame of its author to the public unfamiliar with the history of art. And, despite the commendable effort by Sotheby’s to qualify as a “masterpiece” the portrait of a young man auctioned just under two years ago, the truth is that the chances of acquiring any of his masterpieces can be considered nil, considering that the tondo belonging to the Prince of Liechtenstein has very little chance of coming on the market, and that the fourth version of the story of Nastagio degli Onesti is mostly attributed to a follower. Therefore, and despite the importance and undeniable appeal of the quartet of Post-Impressionist champions seen above, this tondo, a smaller version of the celebrated work on display at the Uffizi, should be considered -a priori- the most desirable and important work in the Allen collection, and should carry a presale estimate well in excess of $100 million.

However, most of the sources consulted indicate that the “unofficial” estimate for this painting is around $40 million, a figure that is initially confusing, considering that in January of this year “Man of Sorrows“, a much less important, complex and attractive Botticelli reached $45 million, and that the aforementioned portrait of a young man exceeded $90 million in 2021. The reason for this is, as is not hard to guess, doubts about the attribution of this painting to Botticelli, to his workshop, or -as Christie’s suggests- to a collaboration between the two.

Christie’s catalog states that “By the late 1480s Botticelli was running a thriving, successful and extremely busy workshop such that the majority of works he produced were, inevitably, executed with a degree of collaboration. Such is likely the case with this painting: Nicholas Penny, Laurence Kanter and Christopher Daly who know the painting first hand, and Carl Strehlke who has studied photographs and technical imaging, consider the principal parts, such as the figures of the Madonna and Child, to have been executed by Botticelli himself, and certain lesser passages, such as the angels’ drapery, to have been worked on with assistance. Previously Federico Zeri and Ronald Lightbown had concurred with the attribution to Botticelli, the latter confirming his view when consulted prior to the sale of the painting to Paul G. Allen in 1999 (verbal communication with Patrick Matthiesen). The superior quality of the Allen panel puts it amongst the best of all such variants produced by Botticelli in his workshop from the 1480s onward.” The literature collected in the catalog indicates that both R.J.M. Olson (2015) and A. Cecchi (2005) attribute the painting to Botticelli and workshop, while authors such as D. Sutton and B.L. Brown seem to admit full authorship by the master.

Image: Detail of the “Madonna of the Magnificat”, ex-Allen version (left) and Uffizi version (right)

Personally, I remember seeing this painting in the catalog of the Matthiesen Gallery, along with other interesting Renaissance works, such as the “Madonna and child with bunch of grapes” attributed to Fra Angelico, or an “Annunciation” attributed to Gentile da Fabriano. In all these cases, they were paintings of obvious quality (the first of which was once attributed to Masaccio), but whose authorship was, to say the least, disputed. Without having seen the painting live, I cannot, of course, give any firm opinion on this “Madonna of the Magnificat“, which judging by the photographs seems a work of superior quality to most of the paintings attributed mostly to Botticelli’s workshop. But this was also the case with the small and attractive “Rockefeller Madonna“, which came up for auction just a decade ago and fetched just over $10 million. With a starting price of $28 million, this attractive but problematic tondo was auctioned for $48.5 million.

The tamed Freud, the wild Johns

Virtually no one has any doubt that “Large Interior, W11 (after Watteau)” will break the auction record for a Lucian Freud painting (something it has already done in the past, when it was auctioned in 1998), and Christie’s refers in the catalogue of the work to an article in “The Times” in which this painting is described as “Lucian Freud’s greatest masterpiece“. And yet, in my subjective and of course debatable opinion, I see more “Freud” in works like “Benefits Supervisor Resting” or “Benefits Supervisor Sleeping” (to cite works auctioned in relatively recent times) than in this painting, the “Freud magnum,” the Freud you can show your children, the Freud that -predictably- will break all records, but which lacks the stark rage of works like the two aforementioned nudes. The painting was auctioned for $86.3 million, evidently a record for the artist.

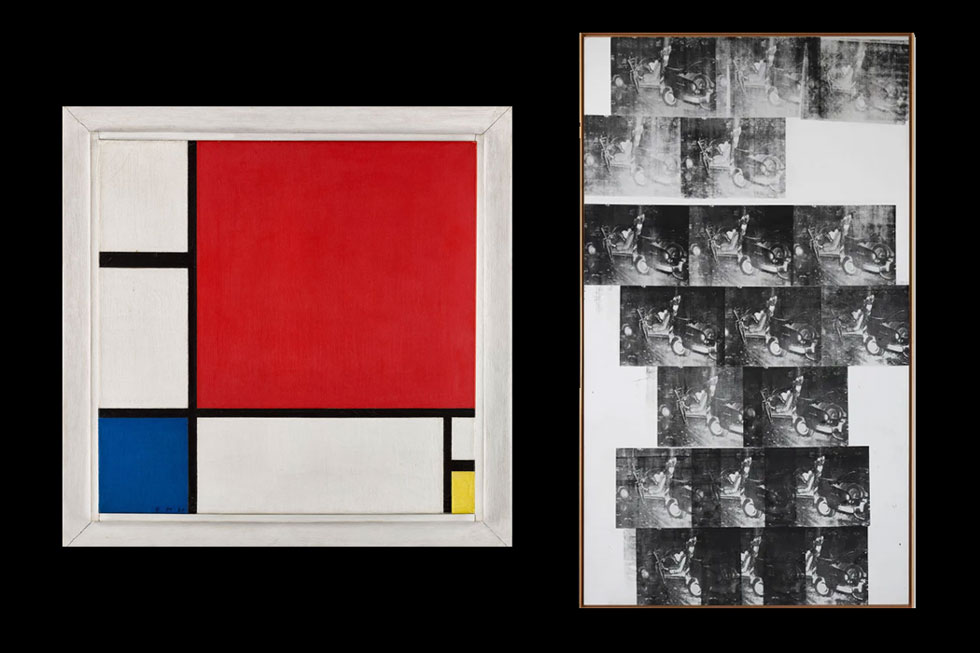

Painted in 1960, “Small False Start” is the smaller version (as in the case of the Seurat, considerably smaller) of the Jasper Johns work sold by David Geffen to Anne and Kenneth Griffin for $80 million in 2006. Christie’s – which defines this painting as “a kaleidoscope of color, medium, process, and meaning” – seems to place the importance of this painting on a par with that of its “big sister”, stating in the catalog that “it is only with works such as ‘False Start’, ‘Jubilee’, and particularly ‘Small False Start’ that we get a clear picture of what Johns is trying to achieve. It is only by freeing both the words and the colors they spell out from their literal and conceptual functions that we get a true representation of abstraction, and subsequently true freedom from the representational qualities of art.” With a presale estimate of between $45 million and $65 million, the painting will further serve to gauge the value of Johns’ major paintings in private hands. “Small False Start” sold for $55.4 million.

The Vedute

As a collector, Paul Allen showed a special interest in landscape painting, and no landscape collection is complete without a painting by J.M.W. Turner, perhaps the most important landscape painter in the history of Western painting. The Allen Collection has this problem solved with one of the artist’s Venetian views, “Depositing of John Bellini’s Three Pictures in La Chiesa Redentore, Venice.” Painted in 1841, it belongs to the last period of the artist’s career, when, as Christie’s catalog indicates, “Turner’s interests turned to the work of Canaletto, the greatest of all vedutisti. Much like Canaletto, the English artist may have been drawn to Venice because, to quote Ian Warrell, “Venice offered unparalleled source material to a talented topographer with a passion for light and water” (op. cit., p. 14). However, in Turner’s hands Canaletto’s rigidly structured views of Venice are taken from a lower angle which in turn enabled the artist to revel in the ephemeral play of light and reflections.” The painting has a presale estimate of between $28 million and $35 million, reflecting that, while it is an interesting work, it is not among the artist’s most outstanding. Without going any further, it is less attractive than “Giudecca, La Donna Della Salute and San Giorgio,” auctioned in 2006 for just over $35 million. It is somewhat difficult to understand why Paul Allen preferred this Turner to others that came on the market during his collecting period, ranging in price from the magnificent “Rome Modern – Campo Vaccino” (one of the most important paintings auctioned this century, acquired by the Getty Museum for £29.7 million in 2010) to the criminally undervalued “Fort Vimieux“, sold for a mere £2.5 million in 2004. The Turner sold for $33.6 million.

Painted in 1874, “Le Grand Canal à Venise,” is a fully Impressionist work by the most direct precursor of Impressionism, Edouard Manet. It is an attractive painting, but by no means one of the artist’s masterpieces. However, the number of Manet’s masterpieces in private hands is so few (perhaps only “La Rue Mosnier aux paveurs” deserves that title) that its presale estimate ($45 million to $65 million) seems justified. “Le Grand Canal à Venise” fetched $51.9 million.

For “tighter” budgets, “Rio San Trovaso, Venise” is an attractive painting by Henri-Edmond Cross that carries a presale estimate of between $2 million and $3 million. And of course, the most famous among the true Vedutists, Canaletto, is represented at auction by “The Piazza San Marco, Venice, looking east towards the basilica,” a painting that comes with the very reasonable estimate of between $5 million and $7 million (possibly because the work was auctioned just eight years ago); and by “The Grand Canal, Venice, looking southeast from San Stae to the Fabbriche Nuove di Rialto,” (presale estimate: $2.5 million to $3.5 million). “The Piazza San Marco, Venice, looking east towards the basilica” was sold for $10.5 million and, surprisingly, the more “modest” “The Grand Canal, Venice, looking southeast from San Stae to the Fabbriche Nuove di Rialto” achieved $11.8 million!

Among the auction’s less anticipated successes, Andrew Wyeth’s “Day Dream” fetched $23.3 million, against a pre-sale estimate of $2-3 million. The same estimate was held by Edward Steichen’s “The Flatiron“, which sold for $11.8 million.

Follow us on: