Leonardo da Vinci – life and works

We, by our arts may be called the grandsons of God

Leonardo da Vinci

A review of all the legends and mysteries about the famous Renaissance painter. His biography and complete catalog. The life and work of Leonardo da Vinci, focusing on his paintings, and debating attributions.

Published: April 2006. Reviewed: April 2020. Texts: by G. Fernández – theartwolf.com

There is no artist more legendary than Leonardo da Vinci. In all the history of Art, no other name has generated more debates, more discussions and more hours of study than the genius born in Vinci in 1452. Painter, sculptor, architect, scientist and researcher, the figure of Leonardo has generated a multitude of legends, myths, rumors about his homosexuality, about his membership or not in countless lodges or sects, strange stories about his stay in Verrocchio’s studio, or his apparently strange relationship with several of his models -apparently derived from his alleged homosexuality – form the long list of Leonardo’s mythology of which the successes of “The Da Vinci Code” and the “Leonardo” TV series are only the most recent examples.

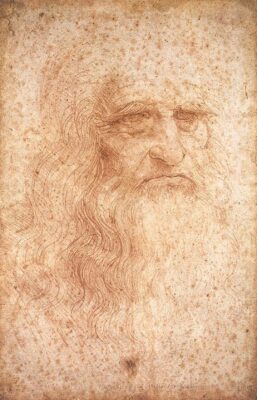

Image: Leonardo da Vinci: “Self-Portrait,” 1516. Red chalk, 33 × 21.6 cm. Royal Library, Turin

Brief biography

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was born in 1452 near Vinci, in Tuscany. Early in his teens, he moved with his family to Florence, and went to work in the studio of Andrea del Verrocchio. Verrocchio, one of the most respected artists of his time, was often helped by his students and assistants, so it is almost certain that the earliest evidences of Leonardo as a painter date from this period. In fact, “The Baptism of Christ” (painted around 1472 and 1475 and exhibited nowadays in the Uffizi Gallery) is generally attributed to Verrocchio and Leonardo. Of the same date is “The Annunciation”, traditionally considered Leonardo’s first painting.

In 1478, Leonardo received his first major commission, a fresco for the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The work, “Adoration of the Magi”, is an ambitious work that Leonardo, for reasons not yet too clear, never finished. In this innovative painting, “nothing remains of the traditional Epiphany, and kings and shepherds are replaced by a multitude of hands, of intensely characterized faces (…) They are not magicians or guardians of flocks, they are living creatures, all creatures with faith and doubt, with the passions and renunciations of life, ‘haloed’ by the creative light of this masterpiece in which light would have no place” (“La obra completa de Leonardo”, published by Editorial Planeta, 1993).

Leonardo da Vinci: “Adoration of the Magi”, c.1478-82. Oil on panel. Uffizzi, Florence ·· Leonardo da Vinci: “The Last Supper”, c.1492-98. Fresco on wall. Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan.

In 1482, Leonardo moved to Milan, where he produced two of his most famous paintings: the first version of the “Madonna of the Rocks” (now in the Louvre, followed by a second version, perhaps painted in collaboration with his workshop) and, above all, “The Last Supper”, painted between 1492 and 1497 for the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, perhaps the most famous religious scene ever painted and the artist’s most celebrated work, second only to the inevitable “Gioconda”. Thus, “each of the characters (…) expresses a different way of approaching the model described in the scene which, also contrary to customary practice, is not communion, but the verbalization of the betrayal that one of the apostles is about to perpetrate” (Estrella de Diego, “Leonardo da Vinci”, 1993).

In 1500 he returned to Florence, already enjoying considerable fame. There he drew his “Madonna and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist” (known today as the “Burlington House Carton”), a work that was admired by his contemporaries, which is remarkable considering that it is an unfinished work. In Florence, Leonardo advanced his knowledge as an architect and engineer, having been hired for this purpose by Cesare Borgia, son of the Pope. Despite this, his work as a painter continued, and it is possible that at this stage he began to work on the portrait of the Monna Lisa. In this sense, he received the most important commission of his life, and which may have given rise to the most remarkable pictorial ensemble of all time: the frescoes for the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, in which Leonardo was commissioned to paint “The Battle of Anghiari”, and Michelangelo “The Battle of Cascina”. Neither work has survived. It is known that Michelangelo never completed the painting, but there are doubts about the progress Leonardo made. To date, there have been several searches for this fresco, which could be hidden under other paintings, but none with success.

Around 1508, Leonardo lived in Milan, working on the equestrian monument of Gian Giacomo Trivulzio. In 1513 he returned to Rome, concentrating on his scientific studies of plants and the human body. In 1515 he entered the service of Francis I of France, who admired Leonardo and soon befriended him. It is believed that it was in France that Leonardo completed his famous “Monna Lisa”. He died in 1519, at the age of 67.

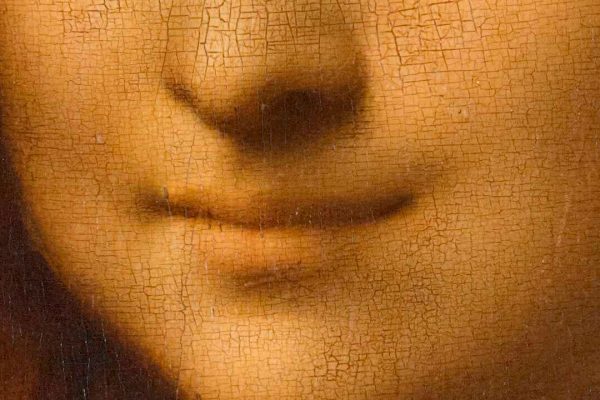

Leonardo da Vinci: “Gioconda” or “Mona Lisa (Monna Lisa), c.1503-19. Oil on panel. Paris, Louvre (set and detail of the smile).

Leaving aside the cheap mythology of the best-sellers, the Leonardo painter offers a continuous source of debate for a very simple reason: it is believed that a great part of the master’s pictorial work has been lost. This has generated that, over the last 150 years countless critics, scholars, or simply attention-hungry folks have brought to light a multitude of paintings publicized as a new Leonardo, “supported” by texts and sketches that “prove” the attribution. The supposed discovery of a new original by Leonardo is always accompanied by an enormous echo in the press and artistic circles, and puts the name of the presumed discoverer in the showcase of the not always cautious world of Art.

Needless to say: the vast majority of these findings are simply garbage devoid of any historical rigor or serious research. Nevertheless, there are some debates and research worthy of comment, and I will try to mention them here.

Leonardo da Vinci: the works, the myths

The “Madonna dei fusi” – Original or copy?

One of the most interesting debates (and that has been addressed with more seriousness) in recent years on the authenticity or not of a work considered to be from the workshop of Leonardo is the one that studies the two alleged most reliable versions of the original – allegedly lost – oil painting by Leonardo representing the “Madonna dei fusi” (“Madonna of the reel”). One of them in the collection of Drumlanrig Castle (Scotland) famous for having been stolen (and recovered) recently, and another, of the highest quality, from the Reford collection in Montreal, and recently acquired by an American collector (there are rumors that the price exceeded 150 million dollars, which is really hard to believe. ) Let’s leave aside the Ruprecht version from Munich, since it is a picture of very different composition from these two.

Leonardo da Vinci (with partial or total workshop intervention): “Madonna of the Yarnwinder (also known as Madonna of the reel) (Madonna dei Fusi)”. Buccleuch (Scotland) and ex-Reford (private collection) versions.

What do we know about the original painting? Basically we have the testimony of a letter sent to Isabel d’Este by Pietro de Novellara in 1501, in which is mentioned “a Virgin sitting as if he wanted to hoist and desired the one and only cross, smiling and holding it, not wanting to give it to his mother, who seems to want to take it” (1). This detailed testimony has long been used as an unquestionable evidence of the non-authenticity of the two paintings we are talking about, guessing that the imitators might have abandoned the symbolism of the reel and the spindle, emphasizing the cross and the sacrifice.

Allright, but… why we must believe so firmly the testimony of Novellara? Is he really a reliable source? We know that even Vasari, the great Giorgio Vasari, have commented artworks that he had never seen, causing historical confusions that lasted until our days. Then, why do we have to admit a priori the truth of that document? Why the written documents have always to prevail over the pictorial documents? Can we invert this reasoning and declare “not reliable” the testimony of Novellara with the evidence we have found not in one, but in three pictorial documents?

And no, our goal is not to declare “not reliable” Novellara’s testimony, it is only to make an artistic analysis not conditioned by it. Also, it is even possible that Novellara were talking about a first version of this subject, and that Leonardo himself could have subsequently painted a second version (notice that Suida, who ignored Novellara’s text, suggested 1506 as the date of execution of the painting) (2) in which he disregarded the symbolism of the reel.

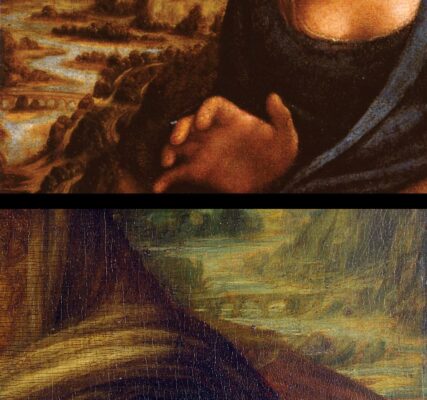

Comparison between the mountain landscape in “Madonna dei Fusi” and in “Madonna, Child Jesus and St. Anne”. Comparison between the Buriano Bridge, depicted in the “Gioconda” and in “Madonna dei Fusi”.

If we ignore this written testimony… what do we have here? Two versions, almost identical in its composition but with notorious differences in the background landscape, and with differences in quality, being the New York version slightly better -in my opinion- than the Scottish one. Let’s make a detailed study of the first version.

It’s not risky to say that this is the best of all the works declared to be by Leonardo’s workshop. It’s a small (50.2 x 36.4 cm.) canvas, originally a panel. The drawing, especially in the face of the Madonna, is highly beautiful; the color is harmonious, with an evident mastery of the sfumatto, although it is possible that the work could have been repainted several times. The face and the hand of the Madonna immediately remind us of the “Saint Anne, the Virgin and the child” in the National Gallery of London, and even of the second version of the “Virgin of the rocks” in the same museum. But the most striking element of the painting is the background, so similar to those in the Gioconda. At this point, I would like to recommend a very interesting study made by Marco Versiero in occasion of the exhibition of the “Madonna dei fusi” in Arezzo, Italy, from July to November of 2000

So, can we now definitely prove the authenticity of the New York version? No, not at all, but it can be used as a gate to the investigation of a period in Leonardo’s oeuvre -the first decade of the 16th Century- in which only a pictorial document is known: the Gioconda. By the way, let’s comment a few things about that work.

The one thousand and one Giocondas

If there is anything more shocking than publishing the authentication of a new Leonardo, it is publishing the authentication of a new version of THE Leonardo, that is, the Gioconda or Monna Lisa. Over the decades, dozens of visionaries who call themselves critics have suggested, in many cases with great fanfare, the existence of another Gioconda, either assuming a second version or denying the Louvre’s celebrated one. Which does not cease to be ridiculous, because the Parisian lady adds to its unquestionable and unmistakable quality an extensive historical documentation, since it was acquired by Napoleon I and even before, that leave no doubt about its authenticity.

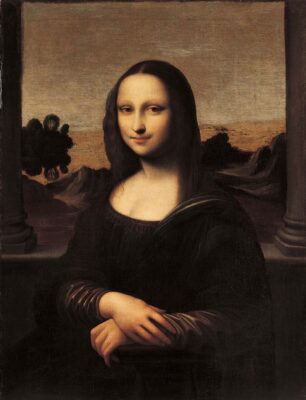

For example, perhaps you know the case of the so-called “Isleworth Monna Lisa”, published as the authentic Gioconda by H. Pulitzer in 1966 in his study “Where is the Monna Lisa?” noticing its high quality and the presence of two columns in the extremes of the canvas (hard to see in the Louvre version) that allegedly confirmed it as the authentic Monna Lisa. The work, which have an unknown provenance until its found in an English private collection, was rejected by most critics. Having been copied in multiple occasions, the existence of a high-quality copy (for example, the one in the Luchner collection, or another one in the Tours Museum) is not a guaranty of its attribution to Leonardo.

Leonardo da Vinci (followers of): Copies of the Mona Lisa, Isleworth and Prado Museum versions.

This is not the only case. Even a historian as respected as Antonio Manuel Campoy, in his monograph on the Prado Museum in 1970, cannot help suggesting the authenticity of the Prado’s version with a speech as deluded as lacking in logic (although this version really has a remarkable quality): “Those who today maintain the primacy of the Louvre’s Mona Lisa over the Prado’s, on what do they base it? If it is on historical news, these are enough for all the arguments you want (?) If it is on the technique, the truth is that the Louvre’s Mona Lisa allows to trace the hand of Leonardo to a very limited extent (??) .” (3) The argument, constituted by two “white” lies, can only be excused if we understand the love that Campoy felt for the Prado, and his evident desire to “enrich” his collections with a work by the Italian master

And so we could go on ad infinitum, mentioning a thousand and one giocondas that a thousand and one visionaries have tried to sneak in, and we could even suggest as a joke -or maybe not- that the day will come when someone will evidence the Leonardesque hand in the mustached Giocondas of Dalí and Duchamp. But this, at least, is a closed case. There is only one Gioconda, and it is in Paris, protected by a thick glass that, by the way, almost prevents her from being seen.

The discussed catalogue

Due to the constant debates about the authenticity or not of Leonardo da Vinci’s works, the catalog of the master’s works remains in constant fluctuation, adding new works that are rejected after a few years, and eliminating others that are later readmitted by certain sectors of the critics. We will comment here on the works universally accepted as authentic.

1. Indisputable works by leonardo

“Portrait of a woman (Ginevra Benci)”

1474-76

Washington , National Gallery

Although at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the last century some discordant voices were heard (4), nowadays nobody doubts the Leonardo’s paternity of this little jewel, which Vasari rightly calls “the most beautiful thing”. Leonardo’s first masterpiece.

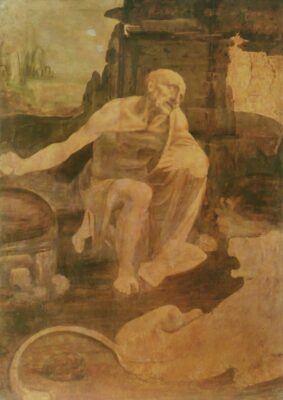

“Saint Jerome”

c.1480

Roma, Pinacoteca Vaticana

This unfinished work has never been in doubt.

“The adoration of the magi”

1481-82

Florencia, Uffizi

As the above, unquestionable

“The Virgin of the rocks”

1483-86

Paris , Louvre

Unquestionable work by Leonardo, with abundant documentation

“The Virgin of the rocks”

1483-86

London , National Gallery

The attribution to Leonardo, at first undisputed, was losing strength at the end of the last century, given the stylistic differences with the Louvre version. However, recent in-depth studies of the painting have demonstrated Leonardo’s paternity (5). The work has probably been repainted with little success, and it is even possible that the wings of the triptych are not by the master, but the central panel is beyond doubt.

“The last supper”

1495-97

Milano, Convento de Santa Maria

Logically unquestionable

“Saint Anne, the Virgin, the child and Saint John”

c.1498

London , National Gallery

Another unquestionable work.

“Portrait of Isabella d’Este”

c.1500

Paris , Louvre

Unfinished and in a mediocre state of preservation, however free of any doubts, with the only exception of Goldscheider (1952), who affirms that only the head is by the master

“Portrait of a woman (Gioconda, the Monna Lisa)”

1503-05

Paris , Louvre

Obviously unquestionable

“Head of a girl (La Scapigliata)”

1508

Parma , Galeria Nacionale

Few discordant voices, among them Ricci and Suida (1929). However, the mastery of the drawing and the numerous historical documents make it an unquestionable work

“Saint Anne, the Virgin and child with the lamb”

c.1510

Paris , Louvre

A never questioned masterwork, although numerous copies are known.

“Saint John the Baptist”

1513-16

Paris , Louvre

A supreme masterwork, with an astonishing technical perfection, and never discussed in a serious way, although Müller-Walde and Berenson (who later changed his opinion) considered it a work by the workshop.

The total is a dozen of works, and we can add one special case:

“The baptism of Christ”

c.1472-75

Florencia, Uffizi

Work by Verrocchio (Leonardo’s master) but it is firmly believed by most critics that one of the angels and the landscape behind it were painted by Leonardo

2. Contested works by Leonardo

“The Annunciation” (c.1472-75) Florencia, Uffizi

For a long time it was considered Leonardo’s first pictorial work. However, in the course of the last century critics were divided between those who maintained Leonardo’s authorship, those who spoke of a collaborative work, perhaps with Lorenzo di Credi, and those who rejected any intervention of the master, opting for Ridolfo Ghirlandaio or even Verrocchio. Personally I reject the latter option, and I consider that the Leonardo – di Credi hypothesis is not at all crazy.

“Virgin of the pomegranate (Dreyfuss Madonna)” (1472-76) Washington , National Gallery

Attribution is doubtful. Perhaps by Lorenzo di Credi

“Virgin offering a flower to the child (Madonna Benois)” (1475-78) Saint Petersburg , Ermitage

A work of rather mediocre quality, discussed since ever, and which surprisingly is today indisputable for most critics (Clark, Berenson, Castelfranco.) Personally, I would not bet on its authenticity.

“The Annunciation” (c.1478) Paris , Louvre

Doubtful, especially when compared to the panel in the Uffizi. Some critics consider it a work in collaboration with the workshop.

“Madonna of the Carnation” (c.1478-80) Munich , Alte Pinakothek

A very discussed work, it has been attributed either to Verrocchio (impossible) or to Leonardo himself, which seems not absurd, given its quality and the existence of many copies of inferior quality.

“Portrait of a woman (Cecilia Gallerani, The Lady with an Ermine)” (1485-90) Cracow , Czartoryski Museum

It is a extremely beautiful, mysterious and profound work, similar in style to “La Belle Ferronnière”, but of even higher quality. It has been deeply and unfortunately repainted, especially on its left flank, which has changed its original appearance and has given rise to many voices that consider it as a workshop work, especially that of Rosenberg (1898) who considers it unworthy of the master or his school (?) The doubts about the authorship of “La Belle Ferronnière” have dragged with them this little jewel, which remains, for the moment, on the list of authentic works. Personally, I have no doubts about its authenticity.

“Portrait of a lady ( La Belle Ferronnière )” (c.1490-95) Paris , Louvre

The attribution of this panel has almost always been linked to that of the previous work, reflecting their stylistic similarities. However, the discordant voices are somewhat louder here. Even so, it is probably the work of the master.

“Virgin milking the child (Madonna Litta)” (c.1490) Saint Petersburg , Ermitage

A terribly repainted work, weird style, especially when compared with the above. Very discussed. Perhaps a work by the workshop.

“Portrait of a musician (Franchino Gaffurio?)” (c.1490) Milano, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana

Some critics have noticed some similarities between this man and the Angel in the “Virgen of the rocks”, but the idea has been discussed by several scholars.

“Portrait of a woman (Beatrice d’Este?)” (c.1490) Milano, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana

Same as the above in style and considerations. Very doubtful

“Salvator Mundi” (c.1500-1510), oil on panel, 65.6 cm × 45.4 cm. Private collection. A very famous work, following its $450 million sale at Christie’s in 2017,. Much has been written (both on theartwolf.com and in books and catalogs) about the debates about its attribution or not, and an in-depth analysis would take up considerably more than the length of this entire page. In summary, we can say that there is a lot of interest in presenting this work as an authentic Leonardo, but much of the specialized critics are not at all convinced. Let’s label it as “doubtful”.

And “that’s all folks”. In total, only 24 paintings, of which only half enjoy “undisputed” attribution. This means that there is still plenty of empty space for new attributions. We at theArtWolf will keep watching.

References:

1. Letter dated April 4th 1501

2 . Suida, “Studi in onore del Verga” , 1931

3 . A .M. Campoy: “El Museo del Prado” Ediciones Giner, 1970

4. Especially Waagen (Die Kunstdenkmaler in Wien, 1866), Suida (1903) and Liphart (1912)

5. Including the recent found by X-rays of an unknown drawing behind the paint.

Leonardo da Vinci: works

More about Leonardo

Follow us on: