Renaissance Art

The modernity that emerged from antiquity

In essence the Renaissance was simply the green end of one of civilization’s hardest winters.

John Fowles

Early Renaissance: Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore (1420-34), by Filippo Brunelleschi (photo by Bruce Stokes) ·· “The Birth of Venus”, (1482-85), by Sandro Botticelli

Perhaps no other chapter of the history of art has been the subject of as much study and admiration as the Renaissance. During a relatively short period of time (about 150 years if we exclude the proto-Renaissance artists), the art and culture of Europe underwent a profound revolution whose effects extended beyond mere cultural manifestations, giving rise to philosophical and political changes that gave birth to the modern era. In Europe, a new, more direct relationship between man and nature was established, one that was not necessarily subject to any divine will imposed from a temple. Within this Renaissance humanism, the artist became aware of his value as an individual and, in contrast to the rigidity of the medieval world, looked back to the models of classical antiquity.

However, it would be a mistake to consider that this whole revolutionary process in the arts and humanities began and ended with the Renaissance. As we saw in the entry devoted to Gothic art, the arrival of money-based economies and the great increase in urban population, together with the appearance of the first Universities as centres of knowledge, created cracks and doubts in the hitherto rigid medieval society. Gothic artists and humanists, as Enrique Valdearcos (“El arte gótico”, 2007) points out, looked not only to God, but also to nature, and “lived under the divine theology but with cracks and doubts that the Romanesque society did not have”. Doubt, as Descartes said, is the origin of wisdom. More than a thousand years earlier, it had been the encounter with new cultures and unknown gods, the idea that if one of these gods was invented, then they could all be invented, which led the Aegean peoples to “the realization that there might be a way to know the world without the god hypothesis” (Carl Sagan: “Cosmos”, 1980). And although Gothic Europe – as well as Renaissance Europe – remained eminently Christian, the gradual shift of interest from the divine to the natural paved the way for the humanism that characterised the Renaissance. And if the Renaissance was that springtime that ended the winter of which John Fowles spoke, the seeds that gave rise to that splendour grew under the light of Gothic stained glass windows, germinating in Giotto’s panels before blossoming in that humanist revolution that began on the banks of the Arno.

Indeed, it was in Florence that the Renaissance first saw the light of day, whether we place its birth date with the paintings of Giotto or with the works of the Quattrocento masters. In the early 15th century, knowledge of and admiration for classical values is evident in the works of Filippo Brunelleschi (the true discoverer of perspective, in the words of Ernst Gombrich), and in the sculptures of Donatello, whose bronze “David” began the revival of the classical nude. In painting, artists such as Masaccio and Paolo Uccello brought the study of perspective initiated by Brunelleschi into the two dimensions.

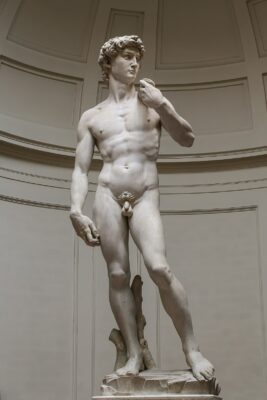

High Renaissance: “David” (1501-1504), by Michelangelo (photo by Jörg Bittner Unna) ·· “Gioconda” or “Mona Lisa” ( 1503-1519), by Leonardo da Vinci

With the figure of Sandro Botticelli, the great colourist of the Renaissance, the interest in classical antiquity was not limited only to formal aspects, but recovered the mythological themes in works such as “The Birth of Venus” (c.1485). Furthermore, Botticelli’s work can be seen as a bridge between the Early Renaissance of the 14th century masters and the High Renaissance, including the “Holy Trinity” of Italian Renaissance art: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael. In this mature phase of the Renaissance, the artists were not only characterised by a technical perfection hitherto unknown, but their ambition led them to become involved in various fields of art and culture. Michelangelo, for example, created in Florence what is possibly the most famous sculpture of the Modern Age, his “David” (1501-1504), just a few years before beginning one of the most ambitious works in the history of Western painting, the wall paintings of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. Even more remarkable is the case of Leonardo da Vinci, arguably the most legendary of all artists, who not only painted what is possibly the most famous painting in the world (his “Gioconda” or “Mona Lisa”, 1503-1519) but also wrote interesting technical and scientific studies.

The interest in the classical world is particularly notable in Renaissance architecture. There is a return to order, rules and geometry within this humanist spirit, as opposed to the imposing spaces of the Middle Ages. For Bruno Zevi, what really distinguishes Renaissance architecture is that it shows “a mathematical reflection developed on Romanesque and Gothic metrics. An order, a law, a discipline is sought against the incommensurability, infinity and dispersion of Gothic space and against the fortuitous and casual of Romanesque” (Bruno Zevi: “Saper vedere l’architettura “, 1948). Figures such as the aforementioned Filippo Brunelleschi or Leon Battista Alberti recovered elements of classical origin, a trend that reached its zenith with Donato Bramante and his famous Tempietto of San Pietro in Montorio.

Renaissance outside Italy: “Hare” (1502), by Albrecht Dürer ·· The Ambassadors (1533), by Hans Holbein the Younger

Outside Italy, the Renaissance spread more slowly, encountering greater obstacles in getting rid of its medieval heritage. Developed at the same time as the painting of the Italian Quattrocento, the works of the Early Netherlandish Painters, in which Gothic forms and themes are still evident, show no trace of the recovery of classical antiquity mentioned above. Despite this, the painting of these artists, especially in the cases of Jan van Eyck and Roger van der Weyden, is technically impeccable, surpassing that of any Italian painter of his day. In Germany, the leading figure is Albrecht Dürer, who can be considered the Leonardo of northern Europe due to his interest in both art and science. Other notable artists include Albrecht Altdorfer and Lucas Cranach the Elder, in whom there is an evident interest in classical antiquity, and Hans Holbein the Younger, who spent most of his career in England.

Just as there are debates about the date of the origin of the Renaissance, it is not possible to establish precisely when the artistic values of the Renaissance ceased to be predominant. In particular, the artists of Mannerism, such as Andrea del Sarto and Pontormo, and the Venetian painters of the Cinquecento, such as Titian and Tintoretto, although inspired by the masters of the High Renaissance, left behind their interest in classical order, moving closer to the exaggeration and theatricality of what was to be the next great chapter in the history of art: the Baroque.

Text above: G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Renaissance paintings, sculptures, and architecture

Painting

Renaissance paintings embodied realism and employed decorative approaches to enhance the human forms and space. Some of the most recognized paintings are Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper and Mona Lisa, and Botticelli’s Birth of Venus.

The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli is among the early renaissance mythological paintings that used decorative and romanticized views of human nature. Venus, a goddess, is seen descending from the sky (probably on the Island of Cyprus) while a woman waits by the shore to cover her with a flowered fabric. The painting bears the aspect of nudity and romanticism, common aspects of the renaissance. Botticelli’s attention to detail, color, tone, and anatomy is a perfect illustration of the influence brought by renaissance arts.

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci is a religious painting depicting the last supper shared by Jesus during His last days with the disciples. Although it reflected the Convent of Santa Maria Della Grazie in Milan, da Vinci drew inspiration from biblical illusions to create the painting. Like in the middle ages, artists used biblical stories to create art, although da Vinci tried -in some way- to reinvent the story.

Originally, da Vinci used tempera to bring the subtle effects of oil paint, and unlike frescos that had a long-lasting effect, da Vinci’s painting lasted for a short time. Most of his predecessors in this particular art used similar painting approaches such that Judas would be placed on the opposite side of the table alone. At the same time, the other eleven disciples shared the same bench with Jesus. For da Vinci, the announcement of betrayal had not revealed the betrayer, yet he sat between them.

In this painting, da Vinci brings out the faces of disciples as upset and enraged by the strange news as they try to identify the betrayer. Unlike Medieval art that was straightforward, renaissance art incorporated human creativity and psychology by creating imaginary scenes that draw the viewer’s creativity. The Last Supper tried to bring the question of ‘who between us would betray Jesus? Why would Jesus share a meal with a betrayer?’

Another work by da Vinci is Mona Lisa which used Sfumato, a technique that blurred the lines between the subjects to bring a different perspective or dimension in a painting. The painting depicts a smiling woman, although the shadows from either corner of the mouth prevent the viewer from determining the moral nature of the smile. The Sfumato technique allowed artists to mask visible transitions between the objects, colors, and tones. A rather strange aspect is that Mona Lisa’s eyes seem to follow the viewer whenever you change the angle of view.

Admired by artists and art lovers of all ages, Raphael’s The School of Athens in the Stanza della Segnatura is possibly the work that best defines the Renaissance. The painting is not only one of the undisputed masterpieces of universal art, but a double homage to the science and philosophy of classical antiquity, and to the humanist spirit of the Renaissance.

As mentioned above, the greatest exponent of the Renaissance in Northern Europe is Albrecht Dürer, an artist who combined an endless curiosity with an enormous talent, which led him to create a rich corpus of works, ranging from self-portraits to pure landscapes (View of Arco), from complex religious scenes to detailed anatomy studies, or his famous drawings of animals (Young hare) and plants, drawn with the precision of a scientific study. In addition, Hans Holbein the Younger painted in England the fabulous portrait of The Ambassadors, a work that combines realism with a strange symbolism in the foreshortened skull.

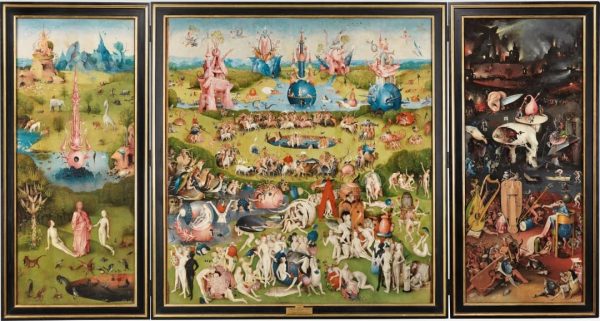

One of the most famous and original masterpieces of Northern Renaissance is Hyeronimus Bosch’s The Garden of Delights. This is a moralizing, didactic work. Bosch saw in the society of his time the triumph of sin and depravation, which had caused the fall of humanity from its original state of sinlessness; and he wanted to warn his contemporaries about the terrible consequences of their impure acts. In this aspect, although chronologically Bosch’s work is situated within the High Renaissance, conceptually it differs from other Renaissance paintings, being closer to the vision of medieval painting. For their part, several works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, such as Dutch Proverbs, replace the pessimistic message of Bosch’s works with a humorous look at local customs.

Sculpture

It is very common when a competition brings out the best talents to the professional world. In 1403, a competition in Florence, Italy, for the best sculpture for the Florence baptistery doors ensued. Hundreds of artists stormed Florence to showcase their talents, and with only one winner for the competition, Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise won the competition. History indicates that the Florence Competition marked the beginning of the Early Renaissance in sculptures. Ghiberti would then open one of the biggest art workshops to train Florence artists and sculptors.

Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise depicts some of the scenes from the life of Jesus using twenty-eight different panels. It is rather impressive to imagine that Ghiberti spent more than twenty-one years completing the panels. The artist used the principles of perspective to enhance the composition and anatomy of the panels. Also, decorations from either side present statues of prophets, a gilt framework of foliage, and bust figures of father and son sculptor.

Michelangelo’s Cristo Della Minerva or Christ the Redeemer is a marble structure found in the church of Santa Maria in Rome, idolizing Jesus carrying the cross. Although commissioned by the Roman Patrician Metello Vari, Michelangelo credited for its design and composition.

One of the renowned renaissance sculptures is David, a marble statue by Michelangelo. One of the Renaissance movement goals is the promotion of realism, which can be seen from David as Michelangelo tries to invoke the reality in Florence under the Medici Family rule. Although the sculpture symbolized the biblical David, the people of Florence saw it as a defense of its civil rights previously compromised by the powerful Medici Family. The glare on David’s eyes and the rather set posture fixated on familiar ground embodies a soldier ready to attack.

Hercules and Cacus by Bartolommeo Bandinelli one of the white sculptures in Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy. The Medici family wanted to show the doubters and challengers that they stood no chance of victory. Hercules, a demi-god, who killed the fire-belching Caucus for stealing cattle symbolizes physical strength, rivaling with the spiritual strength of David.

Architecture

Renaissance architecture replaced ancient Roman forms such as columns, rounded arch, dome, and tunnel vault. Early Renaissance architects such as Filippo Brunelleschi were inspired by the writings of Vitruvius, while the ancient buildings provided the basics of classical architecture.

Architecture in the High Renaissance is credited to Donato Bramante’s illusionary perspective, which can be seen on the Tempietto in St. Pietro in Montorio, a structural dome resembling classical architecture.

The main source of beauty of Architecture in the classical period was proportion. However, renaissance architects established a relation between human proportions and buildings such that space and mass became the differentiating factors. Architecture employed defined ratios of height and breadth, proportion, symmetry, and harmony.

An example of Early Renaissance architecture is the Dome of Florence Cathedral by Filippo Brunelleschi. Brunelleschi used linear perspective, geometry, classical proportions, and harmonious simplicity to draw most buildings. These considerations came to be known as the language of architecture, which was canonized in the Seven Books on Architecture by Sebastiano Serlio.

One of the most famous buildings from the High Renaissance is St. Peter’s Basilica by Bramante, Michelangelo and Bernini, although other architects were involved. The Basilica portrays the symmetrical form of the Greek Cross while the external exhibits massive proportions of masonry. The architecture brings out carved or fractured angles, unlike medieval architecture that used right angles to specify the corners of a building. The building bears Corinthian pillars sit at different angles while the top bears conical ripples.

As in the case of painting and sculpture, Renaissance architecture spread throughout Europe. A clear example is the Château de Chambord, constructed by Francis I, and considered the great masterpiece of Renaissance architecture in France. In Spain, the most important example is the colossal Monastery of El Escorial, the work of several architects, most notably Juan Bautista de Toledo and Juan de Herrera.

Follow us on: