Realism and Academicism

From grey reality to dreamy Arcadia

I have studied the art of the ancients and the art of the moderns, avoiding any preconceived system and without prejudice. I no longer wanted to imitate the one than to copy the other; nor, furthermore, was it my intention to attain the trivial goal of “art for art’s sake”. No! I simply wanted to draw forth, from a complete acquaintance with tradition, the reasoned and independent consciousness of my own individuality.

Gustave Courbet, ‘Realist Manifesto’, 1851

Realism in France: Gustave Courbet: “A Burial At Ornans”, 1849-50. Oil on canvas. Paris, Musée d’Orsay ·· Jean-François Millet: “The Angelus”, 1857-59. Paris, Musée d’Orsay.

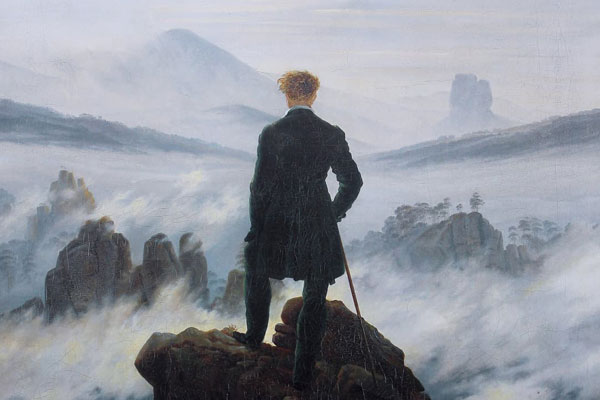

The study of the chronology of Western art, from the end of the classical world to the globalisation that emerged after the Cold War, seems to identify two almost constant phenomena. The first of these is the capacity of art to reflect the ideals and spirit of the society of its time (the zeitgeist), often acting not only as a mirror of it, but also having a significant influence on the evolution of society. If Romanesque was the manifestation of feudal society, Gothic was the fruit of the humanism of the late Middle Ages, which in turn paved the way for the full humanism of the Renaissance. The second of these, in a way linked to the previous one, is that the evolution of art (and, we can deduce, of society itself) seems to respond to a principle of action-reaction in which the existence of a style or movement irremediably prepares the appearance of a subsequent movement with characteristics generally opposed to the preceding one. Thus, the Renaissance order is responded to by the exaggeration and theatricality of the Baroque, which in turn is confronted by Neoclassicism, whose return to order is not accepted by later Romanticism.

It is therefore not surprising that the decline of the Romantic movement in the mid-19th century coincided with the emergence of Realism, which, in contrast to the idealism and subjectivity of Romanticism, advocated an objective view of the reality represented by the work of art. France, the epicentre of this movement, witnessed almost simultaneously the Revolution of 1848 and the publication of Karl Marx‘s Communist Manifesto, followed by a series of articles entitled “The Class Struggles in France, 1848 to 1850”, published in 1850. Artists definitively broke away from the “naïve” idealism of Romanticism and opted for an uncontrived representation of the society in which they lived, paying attention to the life and struggles of the most disadvantaged classes – hitherto generally neglected by art – in works that were sometimes charged with a more or less direct social protest.

Even before 1848, the painters of the Barbizon School began to break away from the principles of Romanticism, among them Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, whose landscapes are a clear forerunner of Impressionism. To the Barbizon School belonged Jean-François Millet, the painter who depicted like no other the hard and even silently tragic life of the French peasants, as can be seen in his great masterpieces, “The Gleaners” and “The Angelus“, both painted around 1857 and now in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The great colossus of realist painting in France was Gustave Courbet, the painter who “turned his painting into an aesthetic and social battlefield, while his artistic innovation led him to be considered the father of Realism” (Pilar de Miguel Egea: “From Realism to Impressionism”, 1989). Among the painters who dealt with social issues was Honoré Daumier, author of the three versions of “The Third-Class Carriage“, painted between 1856 and 1865.

Realism in Russia: Ilya Repin, “Barge Haulers on the Volga”, 1870-73. Oil on canvas. State Russian Museum, St Petersburg ·· Ivan Shishkin and Konstantin Savitsky, “Morning in a Pine Forest”, 1889. Oil on canvas. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Realism spread throughout Europe, and it should be stressed the importance and originality of Russian Realism, often almost exclusively associated with literature due to the two colossal figures of Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The Russian realist painters, the Peredvizhniki, developed a fully realistic style of painting, but with a nationalist undertone that in some ways brought them closer to the then already superseded Romanticism. Thus, “at the heart of the Peredvizhniki’s reforms was the idea of creating a nationally representative and accessible art“. (Inessa Kouteinikova, exhibition review of “The Peredvizhniki Pioneers of Russian Painting,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3, Autumn 2012). The most notable of the Peredvizhniki was Ilya Repin, the great Russian painter of the 19th century, creator of masterpieces with a totally realistic background (“Easter Procession in the District of Kursk” or “Barge Haulers on the Volga“) or a somewhat subjective view of history (“Ivan the Terrible and His Son“). Among the most notable landscape painters were Ivan Shishkin and Alexei Savrasov. In the United States, it is worth mentioning the figure of Thomas Eakins, who had a decisive influence on American realism at the beginning of the 20th century, a movement that will be studied in the entry devoted to American styles.

Realism in France, which, as we have seen, focused on the honest and not always “pleasant” representation of the reality of the times, led the academicist painters to develop a type of painting which, while adopting the realist technique, represented a subject matter closer to the liking of the wealthy classes. This Academicism, sometimes called “bourgeois realism”, is nothing more than “the assimilation of pure realist diction (but not its spirit) by the official classes in order to adapt it to the tastes of the dominant bourgeois classes, in such a way as to avoid offending them” (“Historia Universal de la Pintura”, published by Espasa Calpe, Volume 6, “From Realism to Modernism”).

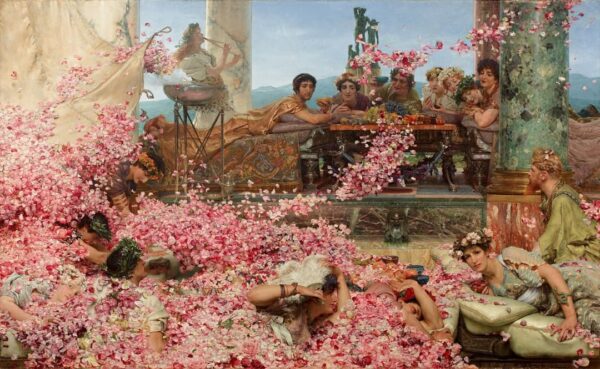

Academicism: Pierre Auguste Cot: “Le printemps (springtime)“, 1873. Oil on canvas. New York, Metropolitan Museum ·· Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema: “The Roses of Heliogabalus“, 1888. Private collection

This gave rise to an academic painting of exquisite technical perfection, which replaced the depictions of peasants and French landscapes with mythological scenes and orientalist landscapes. Among the most prominent artists of this Academicism was William-Adolphe Bouguereau, a long-lived painter who lived to see his work both praised by the bourgeoisie and vilified by the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. Something similar happened to Jean-Léon Gérôme, famous for his historicist and orientalist painting. Pierre Auguste Cot is the author of “Le Printemps” (Springtime) (1873, Metropolitan Museum), a painting which in itself may sum up the decline in the appreciation of academic painting. Exhibited to critical acclaim at the 1873 Salon, it was forgotten for decades and found no buyer when it came up for auction in 2000, although it is undoubtedly one of the great masterpieces of academicist painting.

Outside France, no other painter was as technically perfect as Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, one of the few painters of Academicism whose work is still highly appreciated today. In England, mention should be made of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt. The Pre-Raphaelites are often considered, somewhat ambiguously, part of this academicist style, although one of their characteristics was precisely their opposition to the prevailing trends in the academic art of 19th-century England. Recovering the pre-Mannerist order and drawing on elements of the proto-Romanticism of Fuseli and Blake, the Pre-Raphaelites are considered one of the clearest antecedents of Symbolist painting.

Text: G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: