Paleolithic Art

The Art of Survival

For people of the prehistoric era, representational and abstract art had a symbolic importance that matched the labor required to paint in the deep recesses of caves, move enormous stones great distances, or create elaborately ornamented masks. This art and architecture connected the worlds of the living and the spirits, established social power hierarchies, and helped people learn and remember critical information about the natural world. It was not art for art’s sake, but it was one of the fundamental elements of our development as a human species

Marilyn Stokstad and Michael Cothren: “Prehistoric Art”, 2010

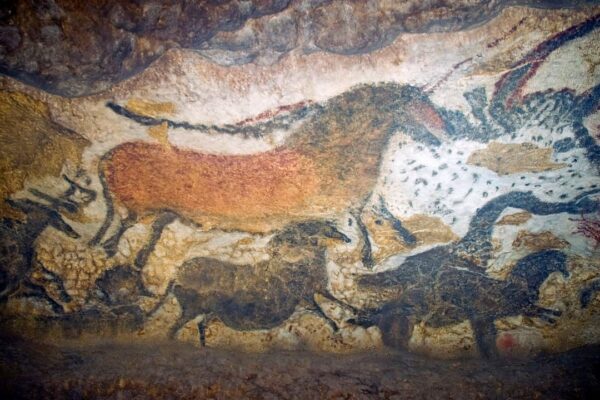

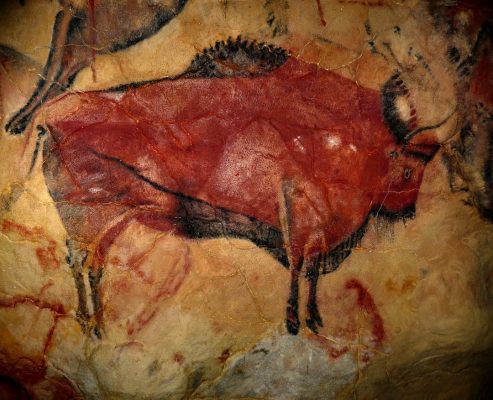

Images: Paintings at Lascaux Cave (reproduction at Lascaux II), c. 15,000 b.C. Photo by Jack Versloot ·· Reproduction of a bison from Altamira, c.22,000 b.C.

When did art began? What was the first art in the world?

Two possibly insurmountable problems stand in the way of answering questions such as the above. First, the definition of what is art -and what is not art- is not clear, and has changed over time, from the somewhat rigid medieval idea of “liberal arts” to the questions raised by the latest artistic trends, including computer-generated “non-human art”. It is possible that even some of the earliest hominids developed an aesthetic criteria when carving a spearhead or similar tool, but whether this qualifies as “art” is quite doubtful.

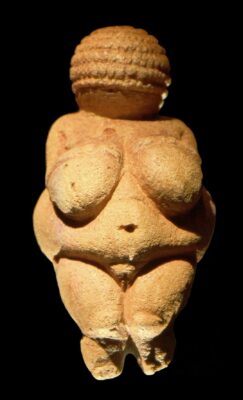

On the other hand, time has destroyed most of the objects (artistic or otherwise) created by the Palaeolithic inhabitants. While several examples of mural cave painting or even small stone figures have survived to the present day, other forms of artistic expression have been lost. As Professor Eduardo Ripoll (“Historia del Arte”, Volume 3, 1989) points out, leather decoration or basketry may have existed, but all examples have been lost. And of course, beyond the world of the visual arts, any examples of primitive music have been lost forever. The examples of Palaeolithic art that have survived to the present day have been categorised in different ways by different authors and at different times, but there now seems to be some consensus on the applicable categorisation. In a paper published in 2013, Óscar Moro Abadía and Manuel R. González Morales examine several publications related to Palaeolithic art, pointing out that “the picture that emerges from this textual corpus is homogeneous. Analysis of these publications demonstrates that Paleolithic representations are first and foremost divided into parietal and portable categories. The former includesengravings, bas-relief sculptures, paintings, drawings, stencils, and prints found onthe walls of caves (cave art) and on open-air stone surfaces (rock art). The latterrefers to a heterogeneous range of portable items, including statuettes and ivorycarvings, engraved bones and stones, personal ornaments, and slightly modifiednatural objects“. (Óscar Moro Abadía and Manuel R. González Morales, “Paleolithic Art: A Cultural History”, 2013).

Images: “Lion Man” from Hohlenstein, Germany. c.40,000 – 35,000 BC. Photo by Dagmar Hollmann / Wikimedia Commons. CC 4.0 licence ·· Venus of Willendorf, c.27 500 – 25 000 BC, Austria. Photo by Matthias Kabel. CC License 3.0

In terms of meaning, the oldest surviving manifestations of figurative art are related to animals: both the mural cave paintings (Chauvet in France or Lubang Jeriji Saléh in Borneo) and the sculpture of the Löwenmensch Lion-man are testimonies of hunting people. And although the meaning of these works is still unclear (various theories have been put forward, pointing to religion, shamanism or even art for art’s sake), the care and detail of the works show the almost divine importance that these peoples attached to the animals with which they coexisted, and on which their very existence depended. Teresa Chapa, archaeologist and professor, wrote that “all authors agree that art is a form of language, expressing a message understandable to the human groups who made it. This message was probably intended to reinforce the idea of a people who gave extraordinary importance to hunting” (“Las Claves de la Prehistoria”, 1993).

In addition to figurative art, there are examples of prehistoric abstract art. What is its origin, and what is its purpose? Professor Louis-René Nougier (“History of Art”, Salvat Editores, Vol. 1, 1981) distinguishes between “derived” abstract art (pointing as an example to the evolution of paintings found at Lascaux, from the naturalistic goat to the “barbed” decoration) and “pure” abstract art, such as the decorations found on mammoth horns in Mezin, Ukraine. But beyond their interest and undeniable aesthetic value, the purpose of these works is still a matter of debate. Before accepting any of the theories as valid, we should always bear in mind Grahame Clark’s reflection on the error of judging prehistoric art according to the mentality of our modern culture. For Clark, for the Palaeolithic inhabitants “art is not entertainment or a means of self-expression, but the adaptation to rites and ceremonies connected with birth, death, fertility and the propitiation of evil forces” (“The Awakening of Civilisation”, 1961). But what were these rites and what was the meaning of these ceremonies? We do not know, the context has been lost, buried after thousands of years of human evolution. “We are not in a position to say whether the rite or ceremony consisted in the fact of materially executing the figures or in something that was done in front of them“, concludes Alfonso Moure (“The Origin of Man”, 1989). “This ‘something’, which could be word, gesture, music or oral tradition, is something we can hardly get to“.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: