Art of Ancient Egypt

The gift of the Nile

Soul to heaven, body to earth

Book of the Death, Egypt, c.1550 b.C.

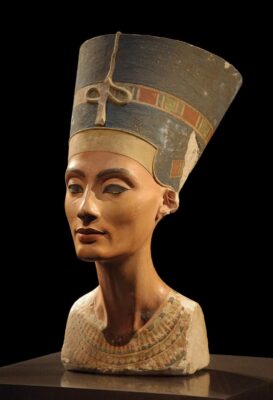

Images: Mask of Tutankhamun; c. 1327 BC; photo by Roland Unger ·· Bust of Nefertiti; 1352–1336 BC, photo by Philip Pikart

Of all the civilisations of the ancient world, none has aroused, and continues to arouse, greater fascination than Ancient Egypt. For more than three millennia, beginning in the late Neolithic period, on the fertile banks of the Nile, Egyptian civilisation maintained its cultural identity, only ended by the conquest of the Romans (who incorporated Egypt into their empire) and the arrival of Christianity, which banned the age-old Egyptian cults and beliefs.

In his “Introduction to the history of architecture”, Doctor José Ramón Alonso Pereira defines this civilisation as the “Egyptian laboratory”, pointing out that “hardly any other country can be found whose structure is so simple and regular, and this geographical structure -so simple and evident- facilitates the abstraction and symbolisation of fundamental concepts“. With the Nile as its south-north backbone, Egypt, “the gift of the Nile”, with its Upper Egypt – Lower Egypt duality, flourished for centuries. In the words of the historian and archaeologist Antonio Blanco Freijeiro, “the isolation imposed by nature and the sufficiency of their resources awakened in the Egyptians an uncommon sense of security, and even of superiority over the rest of the world, whose very existence was sometimes ignored”. When, under the orders of Pharaoh Thutmose I, the Egyptian army reached the Euphrates, the soldiers were fascinated by the rain (“a Nile falling from the sky”) and by the direction of the course of the Euphrates (north-south, as opposed to the Nile), which for them was “a river flowing northwards while flowing southwards” (Isaac Asimov, “The Egyptians”, 1967).

Egypt’s isolation ensured the stylistic continuity of its art, which during the 3000-year dynastic period underwent few changes compared to other great civilisations of its time, such as Mesopotamia or China. In addition to this isolation, there are other reasons for the lack of major changes in the Egyptian style. Emily Teeter (‘Egyptian Art’, 1994) points out that “the Western conception of equating change with positive progress was unknown in Ancient Egypt. On the contrary, the Egyptians believed that the condition of the world was perfect at the time of creation and that earlier styles were to be carefully preserved and emulated”. Thus, the fundamental characteristics of Egyptian art, which first appeared in the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100-2686 BC) and were consolidated during the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 – 2181 BC) did not undergo drastic changes until the advent of the Ptolemaic Period (323 – 30 BC).

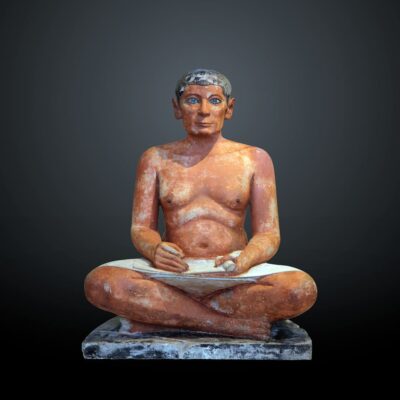

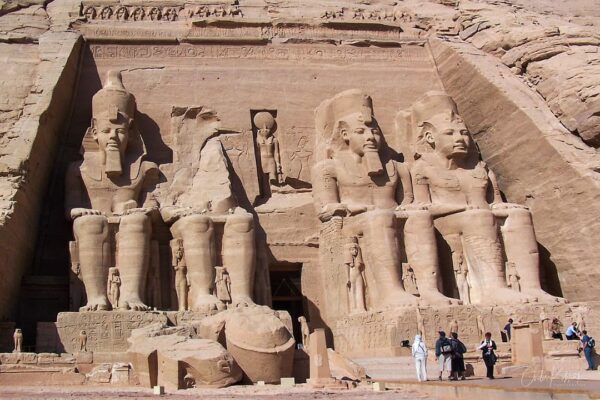

Images: The Seated Scribe, between 2600 and 2350 BC. Photo by Rama ·· Abu Simbel Temples, c.1264 BC, photo by Onder Kokturk

Most Egyptian art was directly related to the belief in the afterlife. Rather than decorative objects, artworks from Ancient Egypt were created to ensure the eternal life of their most prominent protagonists (pharaohs and high dignitaries). With very few exceptions (Thutmose), these are anonymous works, possibly the result of collective effort rather than the genius of a single creator.

Architecture in Ancient Egypt. If we accept Bruno Zevi’s definition that “the history of architecture is, above all, the history of spatial conceptions” (“How to look at architecture”, 1948), then we must pay attention to the idea of Aloïs Riegl, for whom the Egyptian architect had a “horror of space“, voluntarily renouncing the large interior spaces that would have been a clear ambition of Greek and Roman architects. The contrast between the imposing monumentality of the exterior and the almost total absence of large interior spaces is particularly notable in the case of the pyramids, but it also exists in the temples, developed especially from the New Empire onwards, whose interior (especially in the case of the hypostyle hall) is a “forest of columns”, richly decorated with paintings and reliefs.

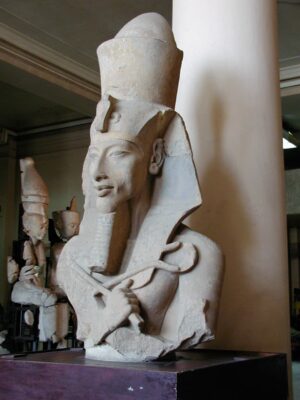

Ancient Egyptian sculpture is “hieratic, ceremonious, solemn. The human figures are extremely respectful of the rules of official etiquette” (Enrique Valdearcos, “Egyptian Art”, 2007). There are, however, exceptions to these general characteristics. One such exception was the art produced during the fascinating Amarna Period under Akhenaten, when it is common to find an exaggeration of form unseen in earlier Egyptian art (although several works, such as the celebrated bust of Nefertiti, maintain realism and ‘officialdom’). On the other hand, a number of animal sculptures and several wood carvings depicting scenes from everyday life (for example, brewery or bakery) show greater creative freedom than the large sculptures of pharaohs or dignitaries.

Images: Monumental statue of Akhenaten. XVIIIth Dynasty, 1351-1334 BC. Photograph by Gérard Ducher, C.C. license 2.0. ·· Pyramids of Giza. Dynasty IV. Photograph by Ricardo Liberato, C.C. license 2.0.

In the case of painting and relief, the Ancient Egyptians generally seem to have held the latter in higher regard, as attested by the fact that the most important tombs were largely decorated with reliefs. However, “even if painting took a secondary place, there are many magnificent pictorial works, the techniques of which encouraged artists to work more freely than relief” (John Baines and Jaromir Málek: “Egypt. Gods, Temples and Pharaohs”, Volume I, 1991). A fascinating example of this creative freedom in painting is the “Frieze of the Goose in Meidum”, created during the 4th Dynasty for the mastaba of Nefermaat and his wife Atet (Itet). During the Roman period, an important tradition of funerary portraits on panels also developed.

The location of these objects in sealed and hidden tombs, the very dry climate, and Egypt’s relatively little contact with other civilisations have favoured the preservation of a large number of works of art. From the 19th century onwards, modern Egyptology revived interest in Ancient Egypt, leading to an increase in the looting of works, but also to the beginning of a series of rigorous excavations that have brought to light previously unknown monuments and works of art, providing valuable information for the understanding of the fascinating civilisation that arose on the banks of the Nile.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: