Neoclassicism

Spirit of Enlightenment

“But the beauty of art demands a higher sensibility than the beauty of nature, because the beauty of art, like tears shed at a play, gives no pain, is without life, and must be awakened and repaired by culture. Now, as the spirit of culture is much more ardent in youth than in manhood, the instinct of which I am speaking must be exercised and directed to what is beautiful before that age is reached at which onewould be afraid to confess that one had no taste for it”

Johann Joachim Winckelmann

Images: Jacques-Louis David: The Oath of the Horatii”, 1784, Musée du Louvre ·· Antonio Canova: “Psyche revived by the kiss of love”, 1793. Paris, Louvre. Photo by Kimberly Vardeman, license cc-by-2.0.

In 1755, a hitherto little-known archaeologist and art historian, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, published “Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst” (“Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture”), a work in which he developed a heartfelt eulogy of classical art, and which became an unexpected international success, a success that the author would repeat nine years later with his most famous work, “History of the Art of Antiquity”. Winckelmann, who had worked on the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum, was a remarkable historian (though not without errors, such as his idea that Greek sculptures lacked polychromy), but his great virtue was his prose, evocative and convincing in its enthusiastic defence of classical antiquity. “The only way for us to become great,” he wrote, “is to imitate the Greeks.”

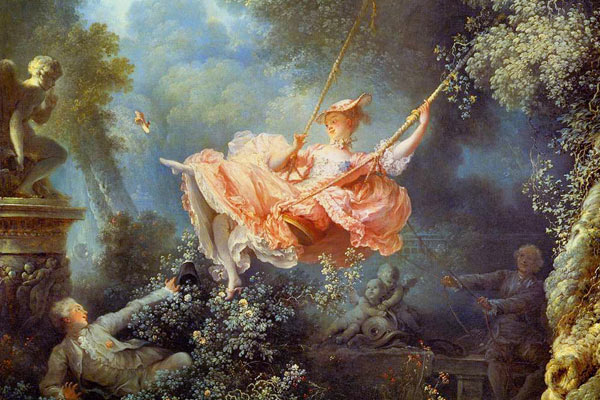

Winckelmann’s ideas came, moreover, at a very appropriate moment. The newly born Enlightenment was proposing a new humanism, an anthropocentric view of the world somewhat similar to that which had emerged during the Renaissance. Moreover, the “Grand Tour“, or the journeys of the European aristocracy visiting Italian monuments, which had already begun in the previous century, gained popularity in the mid-18th century, bringing admiration for classical art to the whole of Europe. All this was the ideal breeding ground for the emergence of Neoclassicism, a cultural movement that sought its inspiration in the art and culture of the classical world, and which opposed the excesses of the Baroque and Rococo, which had been predominant in Europe until the mid-18th century.

It is not surprising that the great pioneers of neoclassical painting were two of Winckelmann’s friends: Anton Raphael Mengs and Pompeo Girolamo Batoni, who were great rivals during his lifetime. However, the great figure of neoclassical painting belongs to a later generation: Jacques-Louis David, who at the beginning of his career preferred Rococo, changed his style when he met Anton Raphael Mengs in Rome. During the decade following his return to Paris in 1780, David painted two of his best known masterpieces, “The Oath of the Horatii” (1784, Musée du Louvre) and “The Death of Socrates” (1787, Metropolitan Museum), works which are, together with his later “Death of Marat” (1793, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Belgium) and “The Intervention of the Sabine Women” (1784, Musée du Louvre), the most recognisable works of the Neoclassical period. One of his pupils, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, is often considered the second great figure of Neoclassical painting, albeit with Orientalist influences, which are visible in his famous paintings of odalisques. The name of Francisco de Goya is sometimes associated with Neoclassicism, although his changing and generally unclassifiable career is closer to Romanticism.

Neoclassical sculpture was inspired, as might be expected, by models from the classical world. Winckelmann’s theory (now considered erroneous) of the absence of polychromy in classical sculpture led to the intensive use of white marble. One of the first great neoclassical sculptors was Jean-Antoine Houdon, whose fame as a portraitist even led him to receive an invitation to travel to the United States, where he created a full-length sculpture of George Washington, now on display in the Capitol in Virginia. However, the pinnacle of neoclassical sculpture is reached in the work of Antonio Canova, who revived classical mythology in masterpieces such as his three versions of “Psyche revived by the kiss of love” (or “Cupid and Psyche”, 1793), the “Venus Victrix” (1805-08, Galleria Borghese) or his two versions of “The Three Graces” (1814-1817).

Images: Palais de la Légion d’Honneur. Photo by JLPC / license CC BY-SA 3.0 ·· United States Capitol, Washington, DC.

In no other discipline is the change from the preceding Rococo to Neoclassicism more evident than in architecture, which is the most extensive chapter of the Neoclassical style. In fact, the formal ideas of Neoclassicism are visible in some buildings that predate the spread of Winckelmann’s ideas, such as the Palladian architecture that appeared in England in the 16th century; and, moreover, buildings in the Neoclassical style continued to be designed in Europe and the United States even in the mid-19th century, when Neoclassicism had already been abandoned in painting and sculpture.

As opposed to the curved and asymmetrical forms of the previous style, Neoclassicism preferred the rationality proposed by the Enlightenment, and to materialise it it resorted to the order and geometry of classical antiquity. But beyond the formal aspect, rationality is present in the conception and design of the building. Neoclassical architects, unlike those of earlier periods, attached great importance to the design process, as is shown by the numerous sketches and technical drawings. “The Baroque ideal of virtuoso technique was succeeded by the Neoclassical ideal of rigorous technique“, wrote Joan Campàs Montaner and Anna González Rueda (“From Neoclassicism to Romanticism”). “The true technique of the artist is that of projecting: all neoclassical art is rigorously projected“.

A unique aspect of neoclassical architecture is that it opened the door for other “neo” styles, the so-called “revivals” (neo-Gothic, neo-Byzantine, etc.), which continued for much of the 19th century (and in a sense can be considered still alive today). It should be noted that, despite the success of these revivals at the time, modern criticism has not, as a rule, been very generous to them. Bruno Zevi never hid his contempt for these movements, describing this period as “an epoch of mediocrity of invention and poetic sterility“. Leonardo Benevolo, for his part, notes that “although the reason for this passage is the desire to maintain continuity with the past, all the theses of traditional architectural culture undergo a kind of overturning. In an effort to adapt the procedures of the past to the needs of the present, these procedures are gradually forced to the limit of rupture“.

Neoclassicism architecture, unlike the Rococo that preceded it, had a presence in virtually all regions of Europe, being especially strong in France (with the so-called Louis XVI Style) and England (with the Adam Style, in reference to the architect William Adam and his sons). Particularly notable is the popularity that the neoclassical style achieved in the then young United States, where it was adopted as the predominant style for buildings of major importance, the most celebrated example being the United States Capitol, begun by William Thornton and completed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

Text: G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: