Raphael

In recent decades, the colossal fame of Leonardo da Vinci (the prototypical Renaissance man, interested in almost all the arts and sciences) and Michelangelo (perhaps the most outstanding of all artists, with enormous talent and ambition in sculpture, painting and architecture) has partly obscured the fame of Raphael, Raffaello Sanzio, usually considered the third figure of the “Holy Trinity” of the Italian Renaissance. And yet, it is possible that Raphael’s contribution to the arts is no less than that of the two aforementioned giants. To his talent as an artist, Raphael added an indispensable task as a conservator of Roman antiquities. Quanta calcina si è fatta di statue et d’altri ornamenti antichi? (“How much mortar was made from statues and other ancient ornaments?”), Raphael complained in a letter to Pope Leo X, in one of his many efforts to prevent the destruction of the remains of ancient Rome. It is not unreasonable to suggest that a considerable part of Rome’s most admired monuments would not have survived to the present day had it not been for Raphael’s efforts.

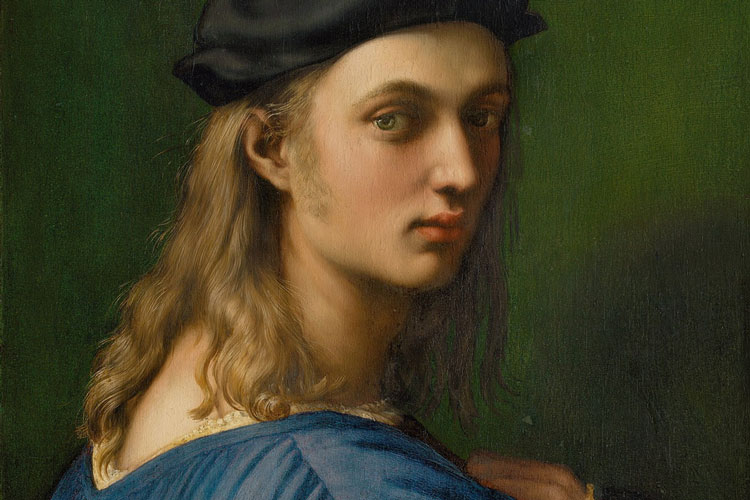

Image: Raphael: possible self-portrait, 1504-06. Tempera on paper, 47.5 x 33 cm. Florence, Uffizi.

Raphael was born in Urbino in 1483, the son of Giovanni Santi, a painter at the Duke’s court, so the young Raphael had contact with painting from childhood. A self-portrait, drawn when Raphael was only fifteen or sixteen years old, bears witness to his precocious talent.

The beginnings in Umbria

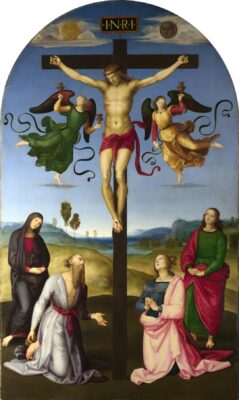

It is thought, although not confirmed, that Raphael may have trained in the workshop of Pietro Perugino, a leading painter of the late quattrocento. In any case, the quattrocentista influence is evident in Raphael’s early paintings, such as the so-called “Mond Crucifixion” (1502-03) in the National Gallery, London, and the “Oddi Altarpiece” (1502-04) in the Vatican Museums.

The great masterpiece of this early period of Raphael’s career is “Wedding of the Virgin”, painted in 1504 and now in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. The work is clearly inspired by a painting of the same title and similar composition by Perugino, painted shortly before and now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen. However, the perspective, the dynamism of the figures in the foreground, the classical tempietto of the background, and the purer and more precise technique separate this work from Perugino’s quattrocentisme.

Raphael: “Mond Crucifixion”, 1502-03. Oil on panel, 283,3 x 167,3 cm. National Gallery, London — Raphael: “Wedding of the Virgin”, 1504. Tempera on panel, 175 x 120 cm. Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan.

Visits to Florence

At the beginning of the 16th century Florence was, of course, the great artistic centre of Italy, and possibly of the whole of Europe. Raphael, without ever taking up permanent residence in the city, spent long periods there between 1504 and 1508, becoming acquainted with the work of the great masters such as Leonardo da Vinci.

In Florence, Raphael painted some of his now admired -and also criticised- “Madonnas”. “Madonna del cardellino” (1505-06, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi) and “Madonna del Prato” (1506, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) are two works similar in size and composition in which Raphael introduces natural elements into the background, perhaps influenced by Leonardo’s works. These Madonnas by Raphael “concentrated in themselves, are somewhat distant. They do not establish any kind of relationship with the world of the spectator (…) The aesthetic and religious vision offered by these images of the Virgin is perfectly in tune with the Counter-Reformation spirit” (Antonio Manuel González, “Raphael”, 1993). However, his most important work of this “Florentine” period was not painted in Florence, but in Perugia. It is “Deposition of Christ” (known as “Borghese Deposition“, 1507, Galleria Borghese, Rome), also influenced (as was the case with “The Wedding of the Virgin”) by an earlier work by Perugino (“Lamentation on the Dead Christ”).

Raphael: “Madonna del cardellino”, 1505-06. Oil on panel, 107 × 77 cm. Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi — Raphael: “Deposition of Christ” (known as “Borghese Deposition”), 1507. Oil on panel, 176 cm × 184 cm. Galleria Borghese, Rome)

Splendour in Rome

At the invitation of Pope Julius II, Raphael travelled to Rome in 1508. His first papal commission was to redecorate several rooms in the Vatican Palace, including the Stanza della Segnatura, a cycle of frescoes -enormous in ambition and exquisite in quality- dedicated to honoring human knowledge, which includes the sensational “The School of Athens”, a double homage to the science and philosophy of classical antiquity, and to the humanist spirit of the Renaissance. It is in these works that Raphael “manifests his brilliant gifts as a painter of the historical genre, capable of capturing and synthesising in detail the entire universal order, at the same time as he contemplates human life framed in perfect harmony, and discovers new paths in the intellectual field until he identifies himself with popular sentiment” (L. Cherubini, “Raphael”, 1992).

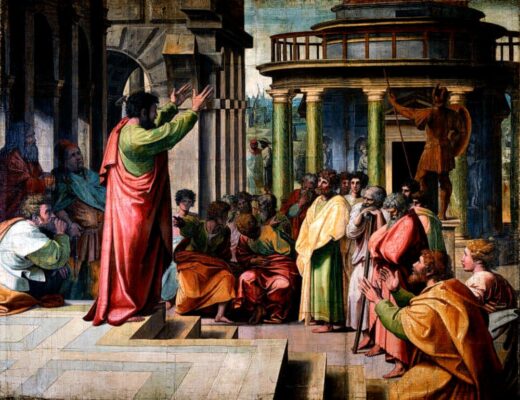

Another important papal commission was the series of ten cartoons (seven of which have survived to the present day) on the life of the Apostles, a series known today as the “Raphael Cartoons“. These works, of large size and intense use of colour, were enormously admired in later centuries, to the point of being called “the Parthenon of modern art”, although there is some debate today about the involvement of assistants in the execution of the works.

Rafael: Stanza della Segnatura, with“The School of Athens”, 1511. Fresco, 500 × 770 cm. Vatican Palace ·· Raphael “Preaching of St Paul in Athens”, 390 x 440 cm. United Kingdom, Royal Collection.

In addition to these large works, Raphael received commissions for smaller but enormously important works. The exquisite “Alba Madonna” (1511, National Gallery, Washington) was commissioned by the humanist Paolo Giovio, and its delicacy contrasts with the strength of “Portrait of a Cardinal” (1510-11, Museo del Prado), an intense, stark portrait consistent with the sitter’s sinister reputation.

In addition to his paintings, Raphael produced some interesting architectural projects, although few have survived today. This is the case of the Palazzo Branconio dell’Aquila, destroyed during the construction of Bernini’s St. Peter’s Square. On a smaller scale, the Chigi Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome still stands.

Raphael: “Portrait of a Cardinal”, 1510-11, Museo del Prado ·· Raphael: Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo. Photograph by Peter1936F.

During the last years of his life, Raphael was interested in printmaking, as well as -as noted at the beginning of this text- being an important advocate for the conservation of Roman antiquities. He died of undetermined causes at the age of 37, and was buried with honours in the Pantheon in Rome, under an inscription that reads: “Here lies Raphael, by whom nature herself feared to be outdone while he lived, and when he died, feared that she herself would die“.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Masterworks by Raphael

More about Raphael

Follow us on: