Dubious attributions and hidden gems: old masters auctions, December 2022

A “poesie” by Titian? An Erasmus that looks like Christoph Waltz? We take a look at the highlights of Sotheby’s and Christie’s London old masters auctions in London, December 2022.

By G. Fernández – theartwolf.com. Pre-auction texts written on 18 October 2022. The news will be updated after the auction with auction results. Amended on 7 and 8 December 2022 with the results of the auction.

The big star of Sotheby’s Old Masters Evening Auction, 7 December 2022 is “Venus and Adonis“, which the auction house attributes to Titian and his workshop, and which carries a pre-sale estimate of between £8 million and £12 million. This is the “Lausanne version” of this painting, which was auctioned at Christie’s in 1998 but went unsold (I seem to recall that there were doubts about its provenance during the Second World War, or at least this was stated in an article in The Telegraph, but I have not managed to recover the source), and it is one of the best known versions of this composition by Titian, of which there are several copies, the one on display in the Museo del Prado being the one usually considered to be the original.

In “Titian’s Later Mythologies” (written in 1996, two years before the failed 1998 auction), William R. Rearick proposed that the Lausanne copy is actually the original painted by Titian -a view disputed by several specialists, including Nicholas Penny- concluding that “in effect, we would propose that in fairly direct sequence Titian painted the Lausanne original, assembled his shop materials such as sketches and ricordifor the first replica, and shortly after undertook the London version for which details of both preceeding versions were reassembled“. In the catalogue of the painting, Sotheby’s states that Rearick’s theory “no longer holds sway but nonetheless the quality he saw in its execution and the originality of its invention has now been recognized by others. More recently, Venus and Adonis has been the subject of a detailed study by Thomas Dalla Costa, who argues in favour of the attribution to Titian with the assistance of his workshop“.

Without pronouncing a verdict on a painting that I have not, after all, been able to see live, the relatively modest pre-sale estimate Sotheby’s assigns to the painting does not seem to indicate that the attribution is very firm. A “poesy” by Titian, even with the collaboration of his workshop, should be extraordinarily attractive to the market. Suffice it to recall that in 1992, another version of “Venus and Adonis” (considered doubtful by several experts, although the Getty Museum -its current owner- attributes it entirely to Titian) was auctioned for some $13.5 million, one of the highest prices paid for a work of art during the early 1990s crisis. More recently, “Diana and Callisto” and “Diana and Actaeon” were acquired in 2009 and 2012 by the UK for around £100 million, although their open market value could easily have been double that. Bids started at £6 million, and the winning bid was £9.5 million, for a final price (including fees) of £11,164,000.

Beyond this presumed Titian, the most interesting work in the auction is “Crucifixion with the Virgin, Saint John the Evangelist and Two Grieving Angels“, which Sotheby’s ascribes to the Bolognese School, 13th century, although the last times it was on the market (in the Simon Dickinson and Moretti Fine Art galleries) it was attributed to the Tuscan School, circa 1280. Despite its small size and far from perfect state of preservation, the work possesses a surprising expressive power, somewhat reminiscent of the imposing crucifix painted by Giunta Pisano around 1250 in Bologna, which may reinforce Sotheby’s theory. With regard to the provenance of this painting, Sotheby’s states that it comes “from a private collection” which, on the basis of its exhibition history, could be the Alana collection, owned by Álvaro Saieh and Ana Guzmán, who three years ago paid €24 million to acquire Cimabue’s “Christ Mocked“. At this auction it has a pre-sale estimate of between £1.4 million and £1.8 million. It is a fascinating work of art which, together with the several works from this period included at the Christie’s auction (which we will discuss later), offers a rare opportunity to assemble a small but interesting collection from a period of major importance in the history of Western art. This excellent work, which was gently held by a Sotheby’s female employee during the auction, was sold for £1,729,000

The name of Canaletto is immediately associated with two ideas: a view of Venice and an unnecessarily long title. “Venice, The Grand Canal, looking north-west, with the Palazzo Pesaro, Palazzo Foscarini, and the pinnacle of San Stae, to the left, with the Palazzo Vendramin-Calergi and San Marcuola, to the right” combines both characteristics and comes to auction with a pre-sale estimate of £3-5 million. Bidding started at £2.2 million, and the final price was £3,665,000. A study for John Constable‘s “The White Horse” -which appears to require cleaning- is offered for between £250,000 and £350,000 (it sold for £289,800), and among the many still lifes included in the auction are two works by John van der Hamen y Leon and Floris Claesz. van Dijck, which could make a good pair. The “display piece” by Floris Claesz. van Dijck sold for £2,092,000, which is more than double its most optimistic pre-sale estimate, a well-deserved success. The Van der Hamen, on the other hand, fetched £277,200, slightly under its most conservative estimate.

Sotheby’s auction also includes a good selection of late 19th century paintings, leaving aside Impressionism. “The Wrath of the Seas” (1886) is one of Ivan Aivazovsky‘s finest paintings to come on the market in recent years, depicting shipwreck victims facing -as the title suggests- the wrath of the sea, a theme the artist also explored in his undisputed masterpiece, “The Ninth Wave“. The painting was auctioned in 2007 for £513,000, and at this auction it has a pre-sale estimate of between £600,000 and £800,000, practically the price obtained in 2007 if inflation is considered. For obvious reasons, this is not the best time for the Russian art market, but collectors who know how to distinguish between art and politics could pick up an excellent work of art for a very reasonable price. “The Wrath of the Seas” fetched £1,729,000, a very, very well-deserved success. “Old Damascus” is a beautiful orientalist painting by Frederic Leighton that has a pre-sale estimate of £1.8-2.5 million, and “Campaspe” is a sensual (explicitly sensual) work by John William Godward that carries a pre-sale estimate of £300,000 – 500,000 and one of the most beautiful introductory texts I have read in an auction catalogue so far this year: “Warm, living, voluptuous flesh is contrasted with cold polished marble and mosaic, in ‘Campaspe’ by John William Godward – one of the artist’s largest and most ambitious paintings. Here is not a pale, tragic and fragile ingénue as may have been painted in the middle years of the nineteenth century, but a more red-blooded, confident woman of the end of the century – monumental, seductive and languorous.” “Old Damascus” was auctioned for £2,213,000, and the sexy Campaspe has a new owner who paid £1,305,500 for her it. The Campaspe sale incidentally produced one of the funniest moments I can recall at an auction in a long time, when the bid of “one million and fifty” was reflected on screen as £1,000,050 instead of £1,050,000, which was quickly corrected.

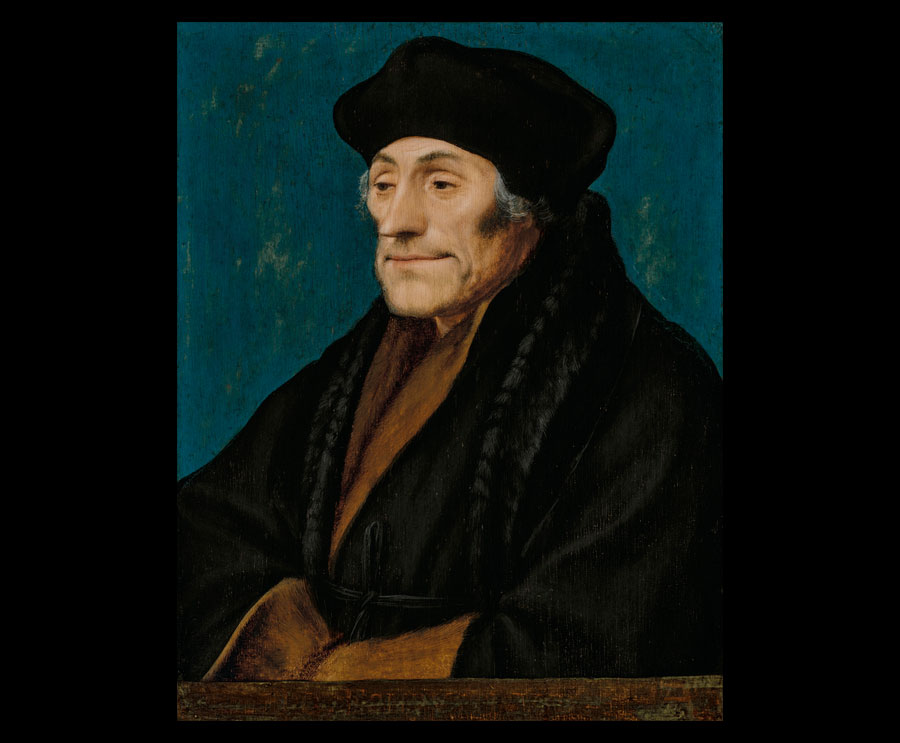

Christie’s Old Masters Evening Auction (8 December) also includes several paintings of uncertain attribution that are worth commenting on. The most interesting is a “Portrait of Desiderius Erasmus” which Christie’s attributes to Hans Holbein the Younger and his workshop. This, of course, is a big deal. Hans Holbein the Younger is one of the great masters of the Northern European Renaissance, and the appearance of one of his paintings on the market is an extremely rare occurrence. In fact, I do not recall any painting attributed with certainty to Holbein coming on the market in recent decades, as the attribution of the “Portrait of Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger” that Sotheby’s unsuccessfully attempted to sell in 2006 is quite dubious. Christie’s (which publishes a pre-sale estimate of between £1 and £1.5 million for this painting, which means that the attribution is unconvincing to say the least) relates this work to the portrait of Erasmus from the Metropolitan Museum, generally considered to be by Hans Holbein the Younger, although -as Christie’s states in the catalogue- “workshop participation has been suggested: the evidence of pouncing establishes that it was based on a cartoon. Erasmus’ proper right eye is perhaps slightly awkwardly set, and there is more than a hint of stubble.“

It is true that Holbein, like almost all successful painters of his time, had help from his workshop, although this is more usual in large paintings, such as the “Henry VIII and the Barber Surgeons” from the Worshipful Company of Barbers in London. And why does this Erasmus look like Christoph Waltz? This disputed work was sold for £1,122,000.

Another painting with a somewhat problematic attribution is “Portrait of Isabella Clara Eugenia (1566-1633), Governess of Southern Netherlands, as a widow, three-quarter-length“, which Christie’s attributes to Peter Paul Rubens and his workshop, and which has a pre-sale estimate of between £400,000 and £600,000. In the catalogue, the auction house states that “the present, hitherto unpublished, canvas has emerged, after restoration treatment, as one of the most compelling known portraits of this type. There are a number of clear pentiments that are now visible, notably the adjustment of the black veil on her (proper) left, and the repositioning of the fingers on her right hand. Rubens’ typically confident, spontaneous brushwork creates a sense of true volume in the drapery and the modelling of the face lends sharp characterisation to the sitter’s features.” This painting was withdrawn before the sale.

Beyond these “problematic” paintings, the two works (in this case of firm attribution) with the highest pre-sale estimate are Sir Anthony van Dyck‘s “Portrait of Queen Henrietta Maria, three-quarter length, in a gold gown” (£2-4 million) and Jean-François de Troy‘s “The Reading Party” (£2-3 million). The Van Dyck was sold for £2,442,000. The de Troy fetched £2,922,000. Both are works of high technical quality, the former baroque and solemn, the latter rococo and joyful. But despite this, neither manages to attract my attention as much as a group of paintings also included in the auction and which, in my opinion, should attract the interest of those collectors truly interested in the history and evolution of Western art, although I fear they will not.

This is a group of 13th- and 14th-century Italian paintings, which could accompany the excellent painting of this period that Sotheby’s includes in its auction, discussed above. The group begins with a “The Madonna and Child” attributed by Christie’s to the Master of the Baptistery of Parma, and painted around 1240-1260 (pre-sale estimate £300,000-500,000). Paintings from the mid-13th century very rarely appear on the market, and this work (rigid, hieratic, Byzantine to the core) could serve as the beginning of a serious collection of Western painting, showing the point from which Cimabue and the great Trecento renovators such as Giotto and Duccio started. Sadly, this work was withdrawn before the sale. Equally interesting are two small panels attributed to the Master of the Dotto Chapel, depicting “The Crucifixion” and “The Last Judgement“, painted according to Christie’s around 1290 (pre-sale estimate of between £250,000 to £350,000 each, sold for £315,000 each). Particularly in the first of these, a narrative intention -far removed from Byzantine rigidity- is discernible. In the catalogue, Christie’s states that these panels, together with others by the same artist held by various museums, were formerly attributed to Cimabue.

These two small panels, incidentally, come from the collection of the descendants of Baron Hans-Henirich Thyssen-Bornemisza, as does another fascinating painting from this group, “Madonna and Child with Two Angels” by Barnaba da Modena, painted between 1370 and 1375 (pre-sale estimate £400,000-600,000). The second half of the 14th century was a dark period in the art of a Europe ravaged by the Black Death, and this is one of the most interesting paintings from that period to come on the market in recent years. There is a striking chiaroscuro -almost a sfumato– on the face of the Virgin and child, and the contrast between the luxurious red and gold background and the Virgin’s black dress is strangely attractive. This stunning painting was sold for £882,000. Closing this group of paintings is a cassone depicting the story of Lucretia which Christie’s attributes to the Master of Charles III of Durazzo, painted between 1380 and 1390, and which has a pre-sale estimate of between £80,000 and £120,000, and sold for £88,200.

Follow us on: