Renoir: ‘The Concert’, 1918

Renoir: ‘Dancer with a Tambourine’, 1918

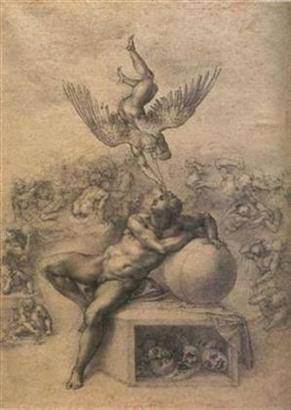

Renoir: ‘Large Bathers’, 1884-87

Renoir in the 20th Century – LACMA

Los Angeles—The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents Renoirin the 20th Century, an exhibition focusing on the last three decades ofPierre-Auguste Renoir’s career, until his death in 1919.

February 14 to May 9, 2010.

]]>

Source: LACMA

The exhibitionpresents approximately 80 paintings, sculptures, and drawings byRenoir, interspersed with select works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse,Aristide Maillol, and Pierre Bonnard, to illustrate the developing avantgarde’sdebt to the older master. Curated by LACMA curator Claudia Eineckeand Chief Curator of European Art J.Patrice Marandel, the show offers anunprecedented look at Renoir through the lens of modernism, bridging theperceived divide between the art of the late nineteenth and the earlytwentieth centuries. Co-organized by the Réunion des Musées Nationaux, theMusée d’Orsay, and LACMA, in collaboration with the Philadelphia Museum ofArt, the exhibition will be on view from February 14 to May 9, 2010

“Renoir in the 20th Century is unlike any other Renoir exhibition,” saysEinecke. “By focusing solely on his later works, it reveals a Renoir whois largely unknown, in a completely new and unexpected context. Thejuxtapositions with Picasso and his modernist peers are astonishing.”During the last thirty years of his career, Renoir moved on fromimpressionism to an art aiming to be decorative, continue the greattradition of European painting, and be modern, all at once. Theresulting paintings and sculptures became an enduring source ofinspiration to a generation of younger artists who were feeling theirway into modernism in the early twentieth century.

Renoir was acclaimed as an emblematic figure of impressionism in the1870s, but even as that movement was winning wider acceptance, he embarkedon new paths of experimentation and innovation. He challenged the basicprinciples of impressionism and, in an overt reference to the past, turnedto traditional drawing and studio work. This period of crisis and researchended in the early 1890s, a decade that brought Renoir public andinstitutional recognition as well as commercial success. Without rejectingimpressionist techniques, Renoir invented a style he described asclassical and decorative. As a declared figure painter, he concentrated onthe female nude, portraits, and studies from the model, in the studio oroutdoors, and experimented with new techniques.

Like his contemporaries and friends Paul Cézanne and Claude Monet, Renoirbecame a point of reference for a new generation of artists. Picasso,Matisse, Bonnard, and Maurice Denis, among many others, expressed theiradmiration for the master, and in particular for his “last manner,”referring to his work at the turn of the century. Great champions ofmodern art, such as Leo and Gertrude Stein, Albert Barnes, Louise andWalter Arensberg, and Paul Guillaume, collected Renoir alongside Cézanne,Picasso, and Matisse.

As an artist who was forever exploring and keen to take up challenges,Renoir wanted to test himself against the great masters from the past,notably Titian and Rubens, but also Fragonard and Watteau, whom he admiredin the Louvre and during his travels. His research was driven by hisrejection of the modern world and a preference for a timeless Arcadiapeopled by sensual bathers and inspired by the south of France, where hestayed often from the 1890s onward. Renoir saw the Mediterranean landscapeas an antique land, at once the cradle and last refuge of a living,familiar, and topical mythology.

In his last years, Renoir persistently returned to a narrow group ofthemes which he explored even in unaccustomed media, such as sculpture. Atthe same time, in the first decade of the twentieth century, his work fromlife and from models yielded new compositions, of which his odalisquesand, above all, the Large Bathers of 1918-1919 (Musée d’Orsay) were thecrowning glory. Renoir himself considered Large Bathers an achievement anda springboard for future research. This was, indeed, how the painting wasseen by many artists in the early twentieth century, especially in thecontroversies surrounding the development of cubism and abstraction: itoffered a working balance between objectivity and subjectivity, betweentradition and innovation, which pointed the way to the classical modernityof the 1920s.

Since then, appreciation of “the late Renoir” has changed somewhat, andhis paintings from this period are now little known. Although hislandscapes and portraits have given rise to major exhibitions in recentyears, there have been no studies or exhibitions focusing specifically onRenoir’s last years, as has been the case for Monet or Cézanne. Renoir inthe 20th Century is designed to remedy this and explore this very fertileperiod in Renoir’s career.

Follow us on: