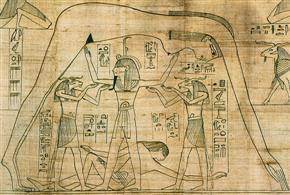

John Ruskin

Fribourg, 1859

watercolor

22.5 x 28.7 cm

British Museum

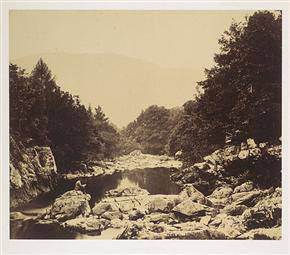

Roger Fenton

On the Llugwy, near Bettws-y-Coed, 1857

print

35.6 x 42.2 cm

Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The Pre-Raphaelite Lens: British Photography and Painting, 1848–1875 On view at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, West Building, from October 31, 2010 through January 30, 2011, the exhibition chronicles the roles photography and Pre-Raphaelite art played in changing concepts of vision and truth in representation in the Victorian era]]>

Source: National Gallery of Art, Washington

The rich exchange between photography and painting is examined in the exhibition through thematic sections on portraiture, literary and historical narratives, modern-life subjects, and landscape.

In the years immediately following the introduction of photography in 1839 a group of British painters calling themselves the Pre-Raphaelites came of age. Looking to the art that preceded Raphael and answering John Ruskin’s call to study nature, these young painters were also motivated by the possibilities of the new medium of photography, particularly its ability to capture every detail.

In their quest to represent the visible world, the Pre-Raphaelites developed a bold new realist language that borrowed from the innovations of photography, including such radical qualities as abrupt cropping, planar recession, and a lack of modulation between forms. Debuting in 1848, their canvases shocked viewers, and the artists were initially accused of painting from photographs. In the decades that followed, photographers were determined to secure for their medium the status of fine art and looked to Pre-Raphaelite visual strategies and subjects extracted from literature, history, and religion.

Cameron, Carroll, Roger Fenton, Henry Peach Robinson, Oscar Gustave Rejlander, and several lesser known photographers had much in common with painters such as William Holman Hunt, John William Inchbold, Millais, and Rossetti, as all contended with the question of how to observe and represent the natural world and the human face and figure. Many of these photographers and painters had personal associations with one another. Select paintings by Hunt, Millais, and Rossetti as well as Inchbold, William Bell Scott, and George Frederic Watts are interspersed with the photographs on view. Works by Ruskin are also on display, including a group of recently rediscovered daguerreotypes. One of them, Fribourg, Switzerland (c. 1854 or 1856), is paired with the 1859 watercolor that Ruskin based on the photograph.

Rossetti’s Jane Morris (The Blue Silk Dress) (1868) is shown alongside photographs of the same subject—artist William Morris’ wife—commissioned and staged by Rossetti himself a few years earlier. Several portraits of the young actress Ellen Terry are exhibited together, including Choosing (1864), which Watts made shortly after their marriage (she wears a wedding dress designed by Hunt). She posed, again in wedding dress, for both Cameron and Carroll not long after. The Pre-Raphaelites also posed for photographers, including David Wilkie Wynfield, Cameron, and Carroll. Moreover, these photographers and painters made similar choices of subjects in nature—sharing compositional and framing devices—as seen in such landscapes as Fenton’s Bolton Abbey, West Window (1854) and Inchbold’s 1853 painting of the same medieval ruins. Finally, groups of works based on Shakespearean, Arthurian, and Tennysonian subjects reveal their obsession with illustrating literary, historical, and mythological heroes and heroines.

Follow us on: