Canaletto

The Stonemason’s Yard

c.1725

London, National Gallery

‘Canaletto and His Rivals’, at the National Gallery ‘Venice: Canaletto and His Rivals’ highlights the extraordinary variety of Venetian view painting, juxtaposing masterpieces by Canaletto with key works by artists including Luca Carlevarijs, Michele Marieschi, Bernardo Bellotto and Francesco Guardi. 13 October – 16 January 2011]]>

Source: National Gallery, London

This landmark exhibition presents the finest assembly of Venetian views by Canaletto and his 18th-century rivals to be seen in a generation

Featured works span the 18th-century, from one of the first accurately datable Venetian views by Luca Carlevarijs of 1707 to the death of Francesco Guardi in 1793. The age of the veduta (view) reached its zenith around 1740, by which time the acquisition of this choice souvenir had become an important element of the Grand Tour of Italy. In the first half of the century, aristocratic travellers, led by English milordi, fuelled a vibrant and highly competitive market for Venetian view painting which saw artists jostling for commissions and fame. Together they immortalised some of the best-loved landmarks of the city including the Grand Canal, the Piazza San Marco, the Rialto, the Molo, Santa Maria della Salute and the Lagoon.

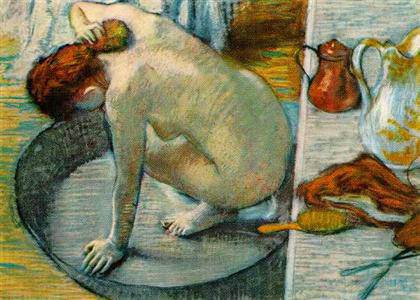

Foremost among these artists was Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto (1697–1768). Trained, like many of his rivals, as a painter of theatrical scenery, he visited Rome in 1719, which inspired him to try his hand at view painting. In the late 1720s, in response to market demand, he began to replace the moodiness of his earlier works with views bathed in warm sunshine. Within a decade, Canaletto had come to dominate the genre. The exhibition features some of Canaletto’s greatest masterpieces, including ‘The Riva degli Schiavoni, looking West’, about 1735 (Sir John Soane’s Museum, London), The Stonemason’s Yard, about 1725 (The National Gallery, London), and four of his finest works from the Royal Collection.

Room 1 opens with a pivotal work by Canaletto’s earliest precursor and the founding father of Italian view painting, Gaspare Vanvitelli (1652/3–1736): ‘The Molo from the Bacino di San Marco’, 1697 (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid). Trained in the Netherlands and based mostly in Rome, Vanvitelli is thought to have visited Venice in 1695, a trip resulting in some 40 views over the following decades. Yet despite being filled with anecdotal detail, Vanvitelli’s Venice remained distinctly placid in comparison to the work of Canaletto and his contemporaries.

The immediate successor to Vanvitelli and the first view painter in Venice to depend on foreign patronage was Luca Carlevarijs (1663–1730). Important early works by Canaletto – including ‘The Piazza San Marco, looking East’, about 1723 (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid) – are displayed alongside depictions of similar locations by Carlevarijs, the artist he had already begun to eclipse.

The largest room of the exhibition celebrates the floating city’s dramatic festivals, regattas and ceremonies, a highlight being Canaletto’s ‘The Molo from the Bacino di San Marco on Ascension Day’, about 1733–4 (Royal Collection). Here too, for the first time, Canaletto’s masterpiece, ‘The Reception of the French Ambassador Jacques-Vincent Languet…’, about 1727 (The Hermitage, Saint Petersburg) is displayed alongside the pioneering composition by Carlevarijs, ‘The Reception of the British Ambassador Charles Montagu…’, about 1707–8 (Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery).

During the 1730s and 1740s the only artist to pose a real threat to Canaletto’s domination was Michele Marieschi (1710–1743), perhaps the most spontaneous of the Venetian vedutisti. Comparisons made in Room 2 demonstrate Marieschi’s characteristically broad brushstrokes and fondness for unexpected view points, a highlight being ‘The Rialto Bridge from the Riva del Vin’, 1740s (The Hermitage, Saint Petersburg).

At the height of Canaletto’s fame, his workshop offered the finest training a view painter could receive. Among those to benefit was his precocious nephew, Bernardo Bellotto (1722–1780). By the age of 18 he could already imitate his uncle’s style with extraordinary dexterity and increasingly sought to introduce ‘improving’ flourishes of his own. Having worked closely with Canaletto during his ‘cold’ period of 1738–42, an almost wintry light remained characteristic of Bellotto’s style for the rest of his career. Yet just as characteristic of Bellotto’s style were his uniquely vibrant blue skies, perhaps most dramatic in ‘The Piazzetta, looking North’, about 1743 (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa).

During the final decade of his life Canaletto had a new rival – Francesco Guardi (1712–1793) – who was to outlive him by 25 years and to provide a glorious final chapter in the history of Venetian view painting. By the 1770s Guardi was considered something of an authority on Canaletto’s work and throughout his career showed a willingness to borrow his compositions. Yet, as juxtapositions in the final section of the exhibition demonstrate, Guardi’s concerns were very different from those expressed by Canaletto.

In his promotion of nature over the works of man, Guardi anticipated the rise of romanticism in the 19th century, and crucially emphasised the fragility of Venice rather than its permanence. Out on the Lagoon, where Venice’s human element is at its most marginal, Guardi appears at his most poetic (View of the Venetian Lagoon with the Tower of Malghera, probably 1770s, The National Gallery, London). While Guardi took this composition from a drawing by Canaletto, his intense concern with mood transforms this quiet backwater into something else entirely.

‘Venice: Canaletto and His Rivals’ presents the finest view paintings of one of the world’s most enthralling and beautiful cities. As well as celebrating the great works of Canaletto, one of the best-loved artists in Britain, the exhibition highlights the exceptional achievements of his now less well-known rivals and associates.

Follow us on: