Arte Tibetano y del Himalaya

Un camino espiritual

Aquellos que, con alegría y devoción

Trabajan para producir

Estupas e imágenes

Tendrán enormes riquezas en todas las vidas

Versos de Selgyal, Kanjur Sutra (citado en “Principios del Arte Tibetano”, Geqa Lama, 1981)

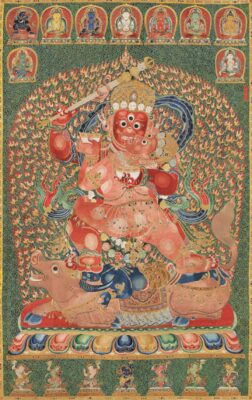

Imágenes: Buda Shakyamuni, siglo XII. Latón, 39,4 cm de altura. Nueva York, Museo Metropolitano de Arte. Imagen vía www.metmuseum.org ·· Raktayamari thangka, principios del siglo XV. Colección privada

Situado a una altitud media de más de 4.000 metros, y rodeado de las montañas más altas del planeta, el Tibet desarrolló una cultura propia, que sintetiza la tradición chamánica Bön con el budismo llegado de la India. Hasta tiempos muy recientes, prácticamente todo el arte del Tibet tenía un trasfondo religioso, con el único objetivo de servir de ayuda para la meditación budista. En palabras del propio Dalai Lama, «todos los elementos de una pintura religiosa tibetana tienen un valor simbólico. Estos símbolos sirven de ayuda para desarrollar las cualidades interiores en el camino espiritual.»

Entre las obras de arte más características del arte del Tibet y de Nepal se encuentran los thangkas, tapices de seda, habitualmente pintados o bordados con una gran variedad de colores, y con una composición característica que incluye una figura central de una deidad rodeada de figuras de menor tamaño. Especialmente notables por su expresividad son los thangkas que representan las forma iracunda de los distintos bodhisattvas, como los dedicados a Mahakala o Yamantaka en el Metropolitan Museum, o el sensacional thangka de Raktayamari, una sensacional obra maestra del arte universal, creado a principios del siglo XV, y por el que un coleccionista chino pagó cerca de 45 millones de dólares cuando la obra fue subastada en Christie’s en 2014.

En cuanto a la escultura, destacan las figuras, habitualmente de pequeño tamaño, realizadas en bronce y otros metales. Es casi seguro que este medio artístico llegó al Tibet a través de Nepal, donde a su vez había llegado procedente de la India. Las figuras religiosas del Tibet, como señala Marco Pallis (“Introducción al arte tibetano”, 1967), reciben un “corazón” en forma de un pequeña pieza de papel que se introduce en un hueco de la escultura, posteriormente sellado. Si este hueco es abierto, la escultura se considera “muerta”, y debe ser “reivivida” de nuevo por una persona cualificada para tal fin.

Además, en el Tibet se conservan interesantes ejemplos de pintura sobre pared, que han sobrevivido gracias al clima seco de la región.

G. Fernández · www.theartwolf.com

Follow us on: