Surrealism

The revolution of the subconscious

Surrealism is based on the belief in the superiority of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dreams, in the disinterested play of thought.

André Breton, ‘First Surrealist Manifesto’, 1924

Metaphysical painting: Giorgio de Chirico: “The Song of Love”, 1914. Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art, New York ·· Early Surrealism: Joan Miró: “The Harlequin’s Carnival”, 1924-25. Oil on canvas. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo

It has already been noted in other chapters that virtually all avant-garde art is indebted to a lesser and greater extent to the experiments of the Post-Impressionist painters and thus to Impressionism. But Symbolism, the enigmatic artistic style of the late 19th century that was largely obscured by Impressionism, also had its admirers in the 20th century. One of them was Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978), an Italian from a noble family who had become acquainted with the works of Arnold Böcklin during his stay at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. At a time when the dominant trend in art was to break with the past, De Chirico was interested in ancient art and architecture, which he found fascinating and enigmatic. He once wrote: “I remember one vivid winter’s day at Versailles. Silence and calm reigned supreme,. Everything gazed at me with mysterious, questioning eyes. And then I realized that every corner of the palace, every column, every window possessed a spirit, an impenetrable soul. I looked around at the marble heroes, motionless in the lucid air, beneath the frozen rays of that winter sun which pours down on us ‘without love’, like perfect song.“

In the five years preceding the First World War, Giorgio de Chirico created the best known of his metaphysical paintings, in which, in a manner similar to Symbolist painting, the juxtaposition of apparently unrelated elements creates enigmatic scenes, generally set in Renaissance-like settings such as squares and streets, with an effect that conveys both calm and unease. “The flat surface of a perfectly calm ocean disturbs us” the painter wrote, “by all the unknown that is hidden in the depth”. After the end of the war, the hitherto Futurist Carlo Carrà (1881-1966) followed De Chirico’s style, as did -briefly- Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964).

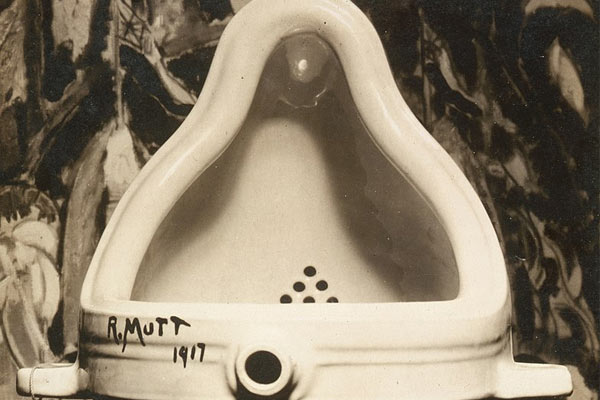

Metaphysical painting (and hence Symbolism) and Dada (discussed in a previous post) are the clearest influences on Surrealism, to which more distant antecedents have also been attributed, such as the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and Giuseppe Arcimboldo. André Breton (1896-1966), who had been a member of Dadaism, published the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, in which he defined Surrealism as a “pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation“. Breton flatly denied that Surrealism came from Dada, but it is undeniable that, with its total questioning of the deepest foundations of art, Dada left open a door through which Surrealism could enter. And, unlike the Dadaists, Surrealism basically adopted a constructive attitude, seeking to reform art in the face of Dadaist negation. “The fundamental difference is Surrealist optimism -the belief in the possibility of change- as opposed to Dadaist nihilism. For some there is nothing but laughter, for others there will be revolution” (María Santos García Felguera: “Las vanguardias históricas”, 1993).

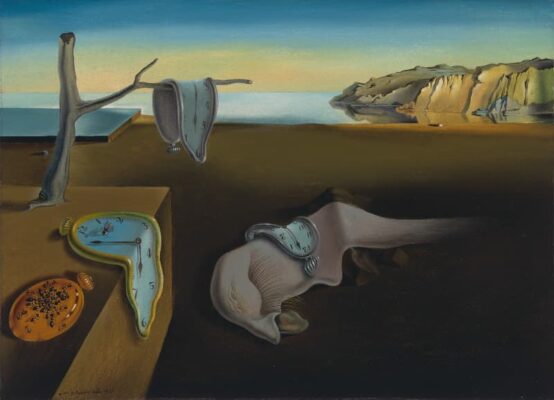

Surrealism: René Magritte: “Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe)”, 1928-29. Oil on canvas. Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) ·· Salvador Dalí: “The Persistence of Memory”, 1931. Oil on canvas. Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York

In the second half of the 1920s, Breton would be joined by what would become the leading figures of Surrealist art. It seems appropriate to begin with Salvador Dalí (1904-1989), perhaps the greatest emblem of Surrealism, eccentric and megalomaniac, “the first to consistently exploit Freud’s discoveries, and to insist that madness is man’s legitimate right” (Conroy Maddox. “Salvador Dalí”, 1979). Beyond his controversial life and ideas (Breton expelled him from the Surrealist movement when Dalí refused to condemn the Nazis), Dalí’s paranoiac-critical painting rank among the great achievements of inter-war art. Catalan like Dalí was Joan Miró (1893-1983), whom André Breton called “the most surrealist of us all“, even though Miró’s highly personal style does not entirely fit in with the principles of surrealism. In this sense, “Miró was creating an unmistakable vocabulary of symbols and ideograms at the same time as he was founding a new pictorial space; all this naturally, without intending to do so. Surrealism was the springboard that allowed him to make this leap” (Melania Rebull Trudel: “Joan Miró”, 1994).

In France, Surrealism was led by Max Ernst (1891-1976), who like Breton had participated in Dadaism and was compared by the historian Herbert Read to William Blake on account of his originality and multifaceted work; and by André Masson (1896-1987), who was one of the first to adopt the Surrealist style, taking part in the group’s first exhibition at the Galerie Pierre in Paris in 1925. Yves Tanguy (1900-1955) developed a personal style of almost abstract Surrealism. Valentine Hugo (1887-1968) is best known for her illustrations and her work for the Russian ballets. Pablo Picasso was also interested in the movement, and even exhibited in the aforementioned exhibition of 1925. The surrealist imprint is unmistakable in such famous works as his “Guernica” (1937) or the sensual portraits of Marie-Thérèse Walter from the early 1930s.

In Belgium, the leading figure of Surrealism was René Magritte (1898-1967). In contrast to the paranoiac-critical fantasy of Salvador Dalí and the almost abstract constellations of Joan Miró, René Magritte (1898-1967) sought to provoke through the manipulation of everyday concepts and images. An enormously prolific artist, creator of over a thousand paintings, Magritte drew inspiration from the symbolism of his compatriots William Degouve de Nuncques and Fernand Khnopff, and from the metaphysical painting of Giorgio de Chirico to develop his unique style, and went on to create some of the most famous works of Surrealism. Magritte’s work had a great influence on his compatriot Paul Delvaux (1897-1994).

Surrealism in Latin America: Roberto Matta: “Psychological Morphology”, 1939. Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid ·· Remedios Varo: “Creation of the Birds”, 1957. Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art, Mexico City.

Surrealism had an important presence in Latin America. The Mexican-born painters Remedios Varo (1908-1963) and Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) had met Breton and Masson in France, and after their exile in Mexico they introduced the Surrealist style to the country, as did the Cuban Wilfredo Lam (1902-1982). The Chilean Roberto Matta (1911-2002), sometimes called “the last surrealist” (although that honour should go to Carrington), developed a fascinating style of abstract surrealism that is sometimes bolder than the Abstract Expressionism that would appear years later. Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) is often framed within Surrealism, although the artist denied it in her own tragically resigned way: “they thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality”.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: