Romanesque Art

A faith carved in stone

“The Romanesque is an art, an architecture, a world of expression that extended throughout Europe, a bond of spiritual community, an attempt at mental unity of the Christian peoples in the face of the previous disintegration and in front of that other great Mediterranean power bloc represented by Arab culture”.

Miguel Ángel García Guinea: “The Romanesque, the second art of European unity”, 2002.

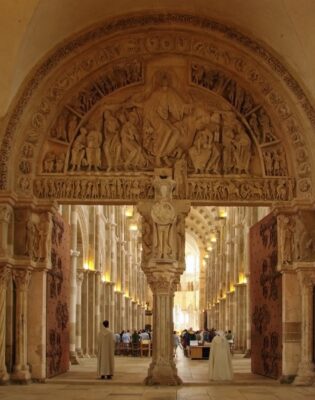

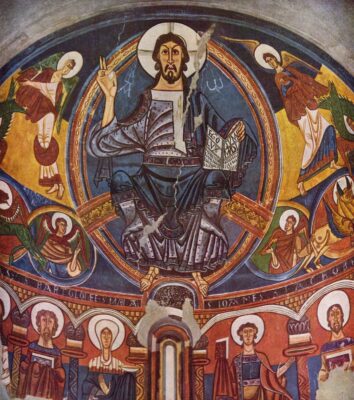

Images: Basilica of Vézelay, central tympanum (1140-1150) ·· Maestro Mateo (Master Mateo): Portico de la Gloria (1168-1188), Santiago de Compostela Cathedral. Photograph by Eduardo De Riquer ·· Master of Taüll: Apse of Sant Climent de Taüll, c.1123. National Art Museum of Catalonia.

Unlike other artistic periods in the history of Europe, whose time frame is clearly delimited by specific historical events (as in the case of Byzantium, with the foundation and fall of Constantinople), with Romanesque Art there is no event that clearly marks its beginning or end. Traditionally it is considered that Romanesque became predominant in Europe around the year 1000 a.C., and that it began to lose importance from the 13th century onwards, with the appearance of Gothic. However, being a multi-national style, it persisted in some regions for much longer, even when Gothic was already flourishing across Europe.

It is important to begin by pointing out that what we understand by Pre-Romanesque art includes a number of regional styles already mentioned in the chapter on the Migration Period and Viking Art. However, that entry was mainly focused on the so-called “barbarian” styles of northern Europe, where the influence of Celtic and other pagan peoples was notable. In southern Europe, with Christianity more firmly established, pre-Romanesque art, especially architecture, is a clear precedent for the Romanesque, like is the case for Lombard architecture (6th to 8th centuries) and Asturian art (8th to 10th centuries). This is not to say that the Pagan influence is only limited to the northern corners of Europe. In fact, although it is an evidently Christian style, clearly related to the feudal society of its time, “Romanesque art retained many elements of the pagan outlook. The barbarian peoples who had made their home in northern and central Europe had not yet come to conceive of the man’s world as a reflection of the divine order. Hence the buildings do not soar up reaching toward the heavens, like Gothic cathedrals.” (Alexandra Wilhelmsen and Heri Bert Bartscht: “The Romanesque”)

Romanesque architecture, although it owes some of its constructive solutions to the Romans, uses stone almost exclusively, moving away from the “Roman concrete” that the Romans had begun to use. It is an architecture with a massive, imposing appearance, which gives great importance to walls and vaults, especially barrel vaults. For Benevolo, during the formative years of the Romanesque style, “the interest of Western builders shifted towards another problem, foreign to Eastern sensibilities: the examination of the physical reality of the structures, investigated in depth beyond the surface of the wall“. (Leonardo Benevolo: “Introduction to Architecture”, 1960). In Romanesque architecture, solid walls are not hidden under mosaics or any ornamental element, while buttresses are defiantly displayed. On the other hand, as Romanesque was, as has been said, a plurinational style (whose extension covers a territory almost coinciding with that of the Western Roman Empire), there are -as was to be expected- notable differences in style between areas.

Romanesque stone sculpture is almost always linked to architecture, and magnificent examples of architectural reliefs have come down to us, such as the Pórtico da Gloria (Portico of Glory) in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, the work of the artist known as Master Mateo, or the sculptures in the Abbey of Saint-Pierre de Moissac. In metalwork, exquisite works were produced, almost always of a religious nature, such as the Shrine of the Three Kings in the Cologne Cathedral.

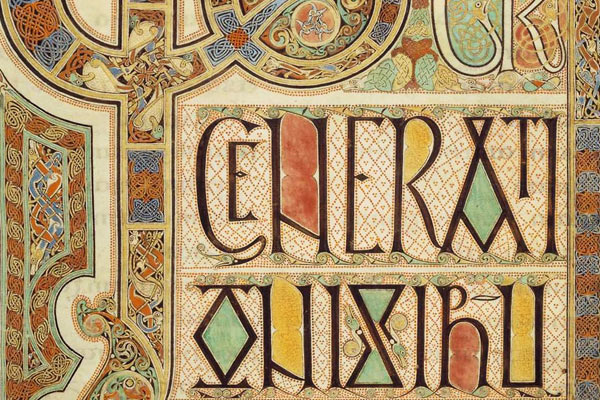

The Romanesque murals that have come down to us, generally of a religious nature, are characterised by somewhat rigid compositions, with no significant advances in drawing, colour or perspective. It should be noted, however, that very few examples of painting on secular themes -in which the artists must have felt greater creative freedom- have survived. More originality is to be found in the field of illumination, especially in British manuscripts such as the St Albans Psalter or the Winchester Bible.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: