Roman Art

The adoption of Venus

“Beauty is produced by the pleasing appearance and good taste of the whole, and by the dimensions of all the parts being duly proportioned to each other.”

Vitruvius

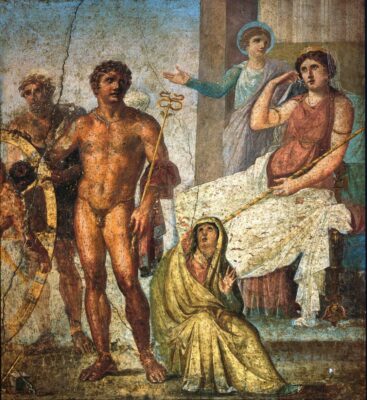

Images: Augustus of Prima Porta. Vatican Museums, Rome ·· “Punishment of Ixion”, from the House of the Vettii, Pompeii. 1st century AD. ·· Dome of the Pantheon of Agrippa, Rome. 118-125 AD. Photograph by Architas.

Roman art has often been considered as a continuation of Greek art, both of which have been included in the term “classical art”. Historically, many authors (Winckelmann, Le Roy) interpreted Roman art as “derivative” or even as a copy of Greek art, and certainly the influence of the Greeks (and, to a lesser extent, the Etruscans) is undeniable. However, Roman art also introduced important innovations, especially in painting and architecture.

It is in Roman sculpture that continuity with Greek art is most evident. According to Anthony F. Janson and Horst Woldemar Janson (“History of Art”, 1995), “the dispute over the question ’Is there such a thing as a Roman style?’ has centered largely on the field of sculpture, and for quite understandable reasons”. As the Roman Empire incorporated territories from Greece, many Greek sculptures were transferred to Rome, to the extent that today many of the sculptures of the Greek masters (Phidias, Praxiteles) are known through Roman copies.

Traditionally, it is considered that the two Roman contributions to the field of sculpture are portraits and narrative relief. As for the latter, “those who first attempted to distinguish Roman art from Greek art started with representations of distinctly Roman subject matter, and the genre that we have come to known as “Roman historical relief” (…) Greek art offered no real precedent for this kind of representation” (Christopher Hugh Hallett: “Defining Roman Art”, 2015). This “historical relief” reaches its highest expression in the bas-reliefs on Roman columns, such as the Column of Trajan or the Column of Marcus Aurelius. Strictly speaking, portraits do exist in Greek sculpture, but the Romans gave this genre a relevance and personality that makes it unique, with famous examples such as the Augustus of Prima Porta (now exhibited in the Vatican Museums) or the destroyed Colossus of Nero.

In the field of painting, extraordinary examples of wall painting have survived, especially at Pompeii and Herculaneum. The Romans made great advances in perspective (as can be seen in several frescoes from the Villa Boscoreale), and are often considered to have introduced landscape painting into Western painting, although the Cretans had already experimented with it at Akrotiri (see the entry on Greek art). In any case, as Roman civilisation expanded, Roman painting increased in complexity and “eventually became idealistic and baroque. The bodies, often arranged in diagonal lines, balance the space-figure relationship with a lively and colourful language” (“Historia del Arte”, 1981, Salvat Editores, Vol. 2).

Although Roman architecture generally adopted the formal language of Greek architecture, saw spectacular technical advances such as the introduction of opus caementicium (Roman concrete) and constructive solutions such as the dome. For Leonardo Benevolo (“Introduction to Architecture”, 1960), “the most important character that distinguishes Roman architecture from Hellenistic architecture is of a negative nature, and consists in the refutation of the traditional limitation of experiences (…). The main consequence of this change of direction is the expansion of the technical repertoire to include vaulted structures“. These developments reached their peak in buildings such as the Pantheon of Agrippa, whose 43-metre diameter dome is still the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world, the Colosseum in Rome, which could hold an estimated 65,000 spectators, and civil engineering works such as the aqueducts or the now destroyed Trajan’s Bridge over the Danube. Roman architecture and the treatises of Vitruvius had a great influence during the Renaissance.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: