Pre-Columbian Art

The legend of the city of gold

Pre-Columbian Art refers to the art produced in the Americas before the arrival of the European conquerors. It is often limited to the areas of Mesoamerica (comprising most of present-day Mexico and part of Central America) and South America, while the art of North America is referred to as Native American Art or, more correctly, North American Indian Art. The latter will be dealt with in a separate entry.

Considering the immense geographical framework it encompasses, which includes virtually all types of climates across two hemispheres, ancient America was the home to civilizations of very different characteristics which produced a wide variety of works of art. Like all the entries in our art history section, this essay is not intended to be a detailed study of the whole artistic output of Pre-Columbian America, but rather an introduction to it, and we encourage you to read more about it, either in the external link at the end of this entry, or through other sources.

MesoAmerica

“In Náhuatl, the language of the Aztec world, one key word for poet was tlamatine, meaning “the one who knows,” or “he who knows something.” Poets were considered “sages of the word,” who meditated on human enigmas and explored the beyond, the realm of the gods.”

Edward Hirsch

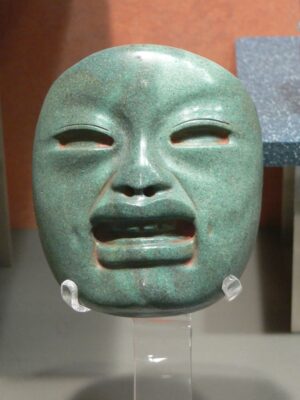

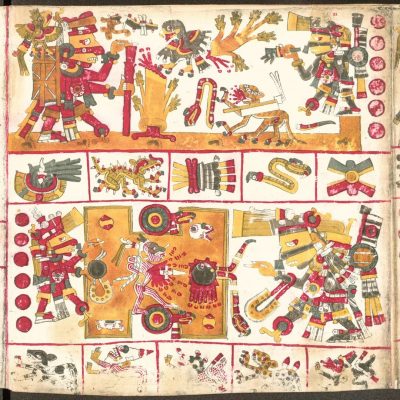

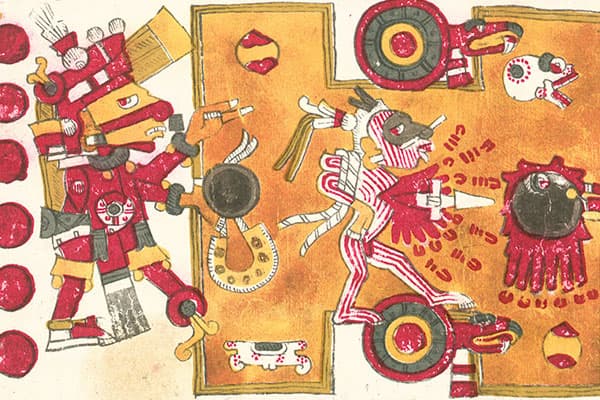

Images: Olmec mask, National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City. Photo by Wolfgang Sauber ·· Giant head representing Quetzalcoatl, Teotihuacan. Photo by Isaact92 ·· Codex Borgia, page 21. Created in Mexico, c.1300 AD.

The art of the Olmec culture, which developed in the territory of present-day Mexico (states of Veracruz and Tabasco) over a period of about a thousand years, between 1500 and 400 BC (although these dates vary depending on the source consulted), initiated the Mesoamerican sculptural tradition. Although the most famous works were the colossal heads, it is possible that the greatest artistic achievement of this civilisation was the extraordinarily expressive jade ‘masks’, whose function is still unclear. According to Karl A. Taube (“Olmec art at Dumbarton Oaks”, 2004), “it is quite possible that such pieces were costume ornaments, such as pectorals or belt pieces. However, it is also conceivable that they served as masks for personified sacred bundles, such as would contain the remains of honored ancestors or images of gods and other esteemed objects”.

The Olmec were the most notable civilisation in Mesoamerica in the Preclassic Period. Within the Classical period, which lasted until the 10th century AD, the city of Teotihuacán was the main centre of artistic production. The Teotihuacans, “in clear contrast to the Olmec tradition, paid little attention to monumental sculpture” (Andrés Ciudad and Mª Josefa Iglesias, “El Arte Precolombino (I)”, 1989), although monumental art is included in various architectural elements. They also stood out for their mural paintings and masks, which were more elaborate but less expressive than the Olmec masks.

The post-classical period saw the splendour of the Mexica civilization, traditionally known as the Aztec civilization. The Aztecs were the largest empire in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, and their artistic production was intended to perpetuate the power of the empire. In fact, they “lacked a word to describe the fine arts“, and “were not concerned with questions of aesthetics, nor did they create objects to be merely observed. On the contrary, they created objects whose purpose was to fulfil a well-defined function – that of indoctrinating common religious, political and military imperatives” (Manuel Aguilar Moreno: “Aztec Art”). In any case, it seems clear that the Aztecs must have taken with them artists and craftsmen from the conquered peoples, thus assimilating part of their artistic production. The few Mexica codices that have survived to the present day are noteworthy. The Mixtec culture, for its part, excelled in the use of ceramics.

Somewhat distant from the previous cultures were the Mayas, located in the Yucatan Peninsula and neighbouring areas to the south. Their architecture, among the most advanced in all of Mesoamerica, has left some fairly well-preserved examples, such as Tukal and Chichén Itzá. As in the case of the Aztecs, the Mayan codices, of which only four have survived to the present day, are noteworthy.

South America

“In these Huari vases one can discern an extraordinarily cubist, modern and completely avant-garde approach, in which the agile and free design is limited by the structured order of the decorated surface. This primitive cubism allows the artist to decompose the images and show them in their essential elements and not in their accessories“.

Pablo Picasso

Images: Chavín Feline-and-Cactus Stirrup Vessel, 900 to 200 BC. Walters Art Museum ·· Lambayeque mask, Peru. Photo by Gusjer.

The history of the art of South America begins with the Caral culture, sometimes called Norte Chico, located in present-day Peru, where urban settlements existed from at least 3500 BC, and which is sometimes considered one of the ‘cradles of civilisation’. Beyond architectural remains, such as pyramidal public buildings, few traces of Caral art have been discovered, most notably a group of statuettes and reliefs made public in 2015. Good examples of pottery and gold and silver works from the Moche and Chavín cultures have survived to the present day.

The interesting Valdivia culture from Ecuador produced, during the third millennium B.C., sculptures of a rather monolithic appearance. Later, the Tumaco-La Tolita culture, which developed along the coasts of what is now Ecuador and Colombia, created excellent pottery and precious metal figures.

The most famous of the pre-Columbian cultures of South America is the Inca civilization. The Incas produced a great variety of works of art, from sculptures to textiles, and it is known that they achieved a great mastery of precious metals (gold and silver), although most of the works made in these materials, such as those created in the ancient temple of Coricancha, were stolen and melted down by the conquistadors. It should be noted, however, that for the Incas the value of gold was not so much economic as spiritual. “There were other materials that were considered of greater value. Jade, not gold, was the substance most valued by the Olmec and Maya, and the Incas and their predecessors valued feathers and textiles above all“. (“Kingdoms of Gold: Sumptuary Art in Pre-Columbian America”, published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017). In relation to this, Victoria Mújica, director of the Gold Museum, explained in 2010 that for the Incas “gold represented the sun. It had no economic or material representation”.

Follow us on: