Post-Impressionism

The multiple paths to modernity

The Post-impressionist painters worked in a broad range of styles, and held differing ideas about the role of Art. However, they were all revolutionaries who sought to create an art that was other than descriptive realism, an art of ideas and emotions. The extraordinary diversity found in this period would provide much food for thought for the artists of the twentieth century

Amy Dempsey: “The Essential Encyclopaedic Guide to Modern Art”, 2002

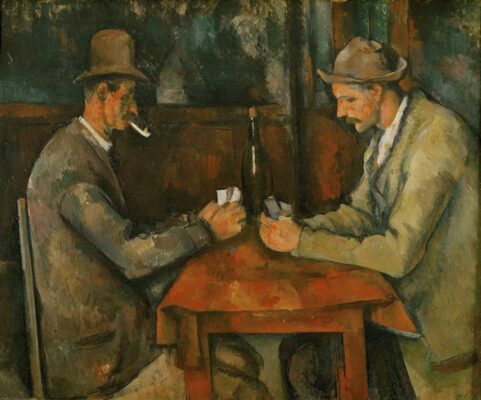

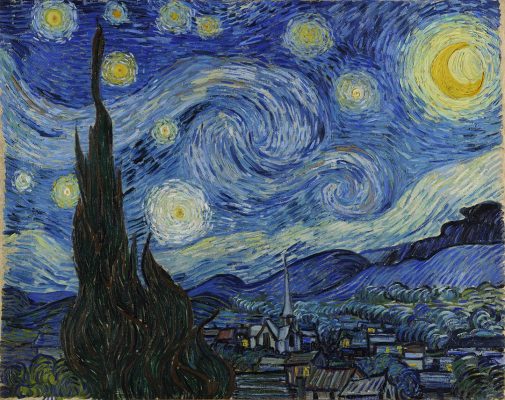

Images: Paul Cézanne: “Card Players”, 1894-95. Oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris ·· Vincent van Gogh: “Starry Night”, 1889. Oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

As discussed in the entry for Impressionism, by the mid-1880s disenchantment began to take hold of the painters who were part of the Impressionist group. This was caused both by the commercial and critical failure of several of the exhibitions and sales organized by the group and by the general feeling that Impressionism as an artistic movement was already exhausted. As if this were not enough, the disenchantment increased during the Eighth (and last) Impressionist Exhibition, held in 1886, to which some young painters whose style was clearly different from that of the Pissarro or Monet generation were invited, which led Degas to demand that the word “Impressionism” not appear on the exhibition poster. All this led many of the great figures of Impressionism to abandon the Impressionist style and seek their own style, as did the painters of the new generation, such as Seurat or Signac. This fruitful period of individual research and experimentation, indispensable for understanding 20th century art, is known as Post-Impressionism.

Post-Impressionism is not an artistic movement. The so-called Post-Impressionist painters shared no other common characteristic than the search for their artistic freedom and an evident taste for experimentation about the possibilities and limits of painting. None of them called themselves “postimpressionists” (in fact the term was coined by the British critic Roger Fry in 1910, when practically all the “postimpressionists” had already passed away), they had no sense of a group, nor did they ever publish any kind of joint manifesto. Thus, instead of looking for misleading common characteristics among these painters, it seems more appropriate to present each artist individually, studying the contribution of each of them to the genesis of modern art.

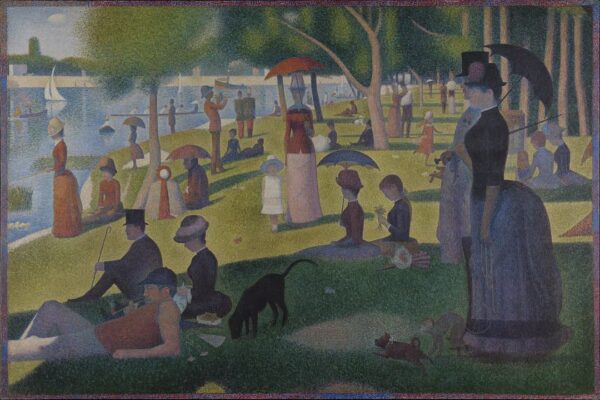

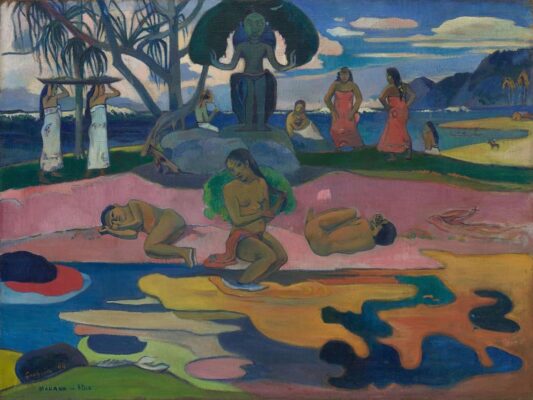

Images: Georges Seurat: “A Sunday Afternoon on the Ile de la Grande Jatte,” 1884-86. Oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago ·· Paul Gauguin: “Day of the God”, 1894. oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago.

One of the first painters to move away from Impressionism (in fact it could be said that he was not really part of the group) was the young Georges Seurat (1859-1891), who at the age of twenty-five revolutionized the Paris of the Belle Époque by presenting two very ambitious works, “Bathers at Asnières” and “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte“, in which he showed the results of his chromatic studies that led to Pointillism. Seurat is “the son of nineteenth-century positivism, with the ambition to extend scientific methods to all areas of human activity (…) and of course to the visual arts” (Manuel López Blázquez: “Seurat”, 1995). When Seurat died in his early thirties, his pointillism was continued in the work of Paul Signac (1863-1935).

Another of the main figures of Post-Impressionism is Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), who even participated in two of the Impressionist Exhibitions, following the example of his admired Pissarro. In the mid-1880s, at the same time as Seurat, Gauguin abandoned Impressionism, traveling to Martinique and Tahiti in search of primitive landscapes, far from modern France. “The concern for intangible form united Seurat and Gauguin. However, while the former sought it in the refined means of civilization, the latter sought to find it outside: among the primitive, the savages” (Ingo F. Walther: “Paul Gauguin”, 1989). Gauguin’s style, sometimes described as symbolist, found continuators such as Paul Serusier, the group of the Nabis, and even the Fauvists of the early twentieth century.

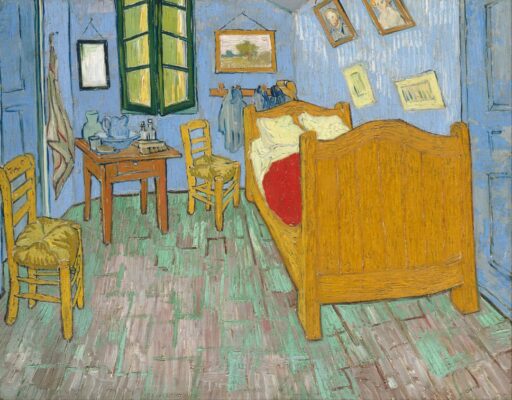

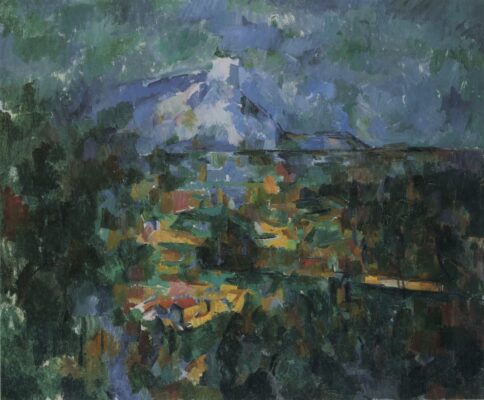

Images: Vincent van Gogh: “Bedroom in Arles,” 1889. Oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago ·· Paul Cézanne: “Mont Sainte Victoire seen from Les Lauves,” 1904-06. Oil on canvas, Kunstmuseum Basel.

Perhaps the name most universally associated with post-impressionism is that of Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) and, paradoxically, he was possibly the only one who never adopted the impressionist style. Although some of his works painted in Paris in 1886 and 1887 show an Impressionist influence, he developed his own style, in which the Japanese influence is even more important. “I am not working for myself alone, I believe in the absolute necessity for a new art of color, design, and artistic life,” Van Gogh wrote in 1888. His paintings, which only gained recognition after his death, are clear forerunners of Fauvism and Expressionism.

But the most important of all the painters of his time, the most decisive figure in the formation of modern art, was Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). Cézanne, like Gauguin, came to exhibit in some of the Impressionist Exhibitions, but he was among the first to separate himself from the group, both stylistically and physically, moving to Provence, where he developed his own style, pre-Cubist, with figures often reduced to simple geometric figures. This evolution in his style is easily noticeable in his series of paintings of “La Montagne Sainte Victoire”, in which the first paintings show a style clearly influenced by impressionism, but the last works, often unfinished, clearly anticipate the cubism of Picasso and Braque. The phrase “Cézanne is the father of us all” has been attributed to both Picasso and Matisse, as a testament to Cézanne’s colossal importance in the genesis of modern art.

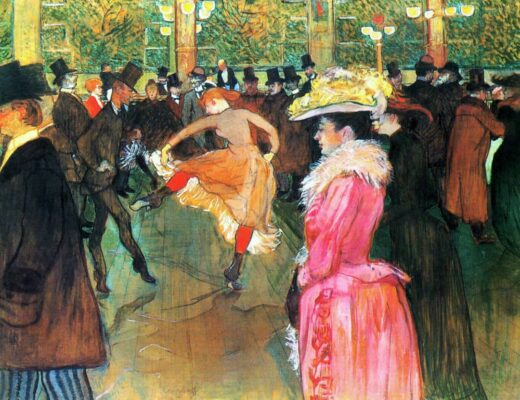

Images: Henri de Toulouse Lautrec: “At the Moulin Rouge”, 1890. Oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art ·· Henri Rousseau: “The Dream”, 1910. Oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Other artists generally associated with Post-Impressionism were Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), the great chronicler of nightlife in Paris at the end of the 19th century, and Henri Rousseau (1844-1910), a self-taught painter whose naïve style was praised by artists such as Picasso. In the case of Claude Monet -the great standard-bearer of Impressionism- his later works, especially those of the “Water Lilies” series, go beyond any Impressionist experiment and, abandoning the spatial concepts that had governed Western painting since the Renaissance, enter the realm of abstraction.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: