Minimalism

Reduction to the essence

There is nothing more contrary to the “shaman” who acts in the heat of the moment, who gives himself in his passion to communicate, than the “minimal” artist who calculates coldly and alone and who risks even denying the validity of any effort, calling into question the “homo faber”.

María Lluïsa Borràs

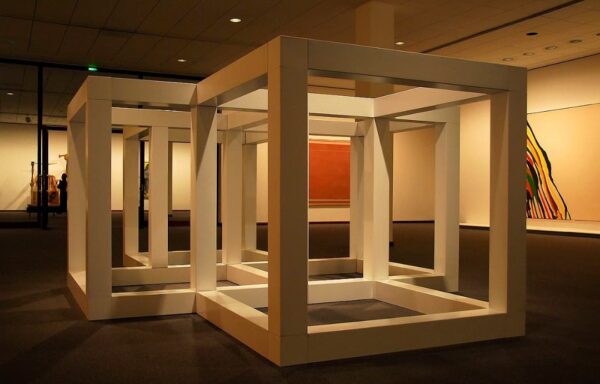

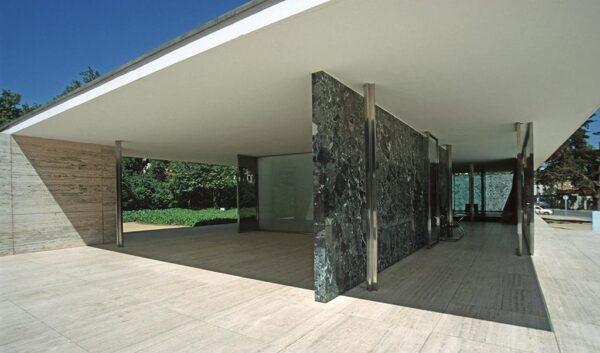

Sol LeWitt: “Modular Cube”, 1979. Neue Nationalgalerie. Photo by Porrovecchio, license C.C. 2.0 ·· Lugwig Mies van der Rohe: German Pavilion (Barcelona Pavilion), 1929 (rebuilt in 1983-1986). Photo by Hans Peter Schaefer, license C.C. 3.0

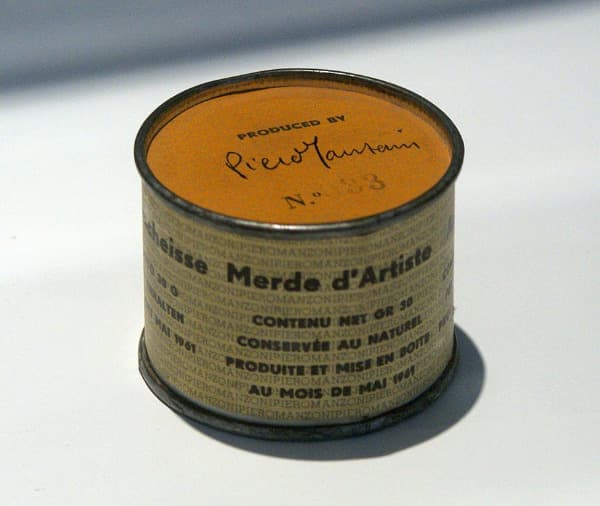

It could be said that, as happened some time ago with the concepts of Romanticism and even Expressionism, the term Minimalism has transcended its use as a definition of an artistic movement to become part of the colloquial lexicon that uses it in very diverse and debatable contexts, sometimes qualifying as “minimalist” that which should simply be called “simplified” or even “incomplete”. In its origins in the 1960s, Minimalism was, like conceptual art, a reaction to the excesses of modernism, advocating for the reduction of the artistic object to its essence (“art pared down to a minimum“, as defined by Barbara Rose in 1965), stripped of everything that the creator considers superfluous, which may include aesthetics, subjectivity or even its ability to communicate or move, qualities usually considered essential to define an object as a “work of art”. In this sense, Valeriano Bozal asked (“Modern and Postmodern”, 1993), “What can be said of an object that seeks to reduce to a minimum, to the point of making them disappear, all or some of these characteristics, an object that does not wish to signify anything, (…) an object that seeks to neutralize all those factors on which the artistic traditionally rests? (…) I am not very sure that it is possible to speak of an artistic object, at least in the natural sense of the word“.

This discussion about whether a minimalist object can really be a work of art has accompanied Minimalism from its origins, and continues today. Despite this, the simplicity (at least conceptual) of the idea of Minimalism meant that it was reflected in practically all creative fields, from visual arts to music, through industrial design, architecture, and even cinema and literature.

In the visual arts, Minimalism, as has been said, arises as a reaction to modernism, especially to the complexity of postwar American Abstract Expressionism. “The project of Minimalism in the work of key practitioners and theorists like Robert Morris, Donald Judd, and Richard Serra, was to oppose the subjectivity and expressiveness of postwar American modernism (…) and develop instead, as Ann Goldstein puts it, ‘art’s conception as a self-referential object situated in physical and temporal space that engages a self-reflexive spectator.’ Instead of an emphasis on the artist and (usually) his self-expression, the works refuse subjectivity and insist instead on their own “objecthood” and materiality”. (Janet Wolff: “The meanings of Minimalism”, 2005)

Donald Judd: “Untitled”, 1988-1991. Israel Museum. Photo by Talmoryair, license C.C. 4.0 ·· Richard Serra: “Contour 290”, 2004. Glenstone Museum. Photo by Ron Cogswell, license C.C. 2.0.

Having Kazimir Malevich and De Stijl artists such as Piet Mondrian as direct antecedents, Minimalism is reflected in painting in the works of Frank Stella (b.1936), Kenneth Noland (1924-2010) or Ellsworth Kelly (1923-2015). But even more than in painting, Minimalism was studied in three dimensions in the sculptures of artists such as Sol LeWitt (1928-2007), who also experimented with conceptual art; Anne Truitt (1921-2004), who endowed her minimalist works with a certain degree of craftsmanship; Donald Judd (1928-1994), who nevertheless never identified himself as a “minimalist”; or Dan Flavin (1933-1996), famous for his installations with fluorescent tubes.

In architecture, Minimalism is often associated with the highly important figure of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969), despite the fact that the architect designed most of his “minimalist” buildings (from the Barcelona Pavilion to the Seagram Building) years or decades before the emergence of Minimalism in the visual arts. Mies is credited, perhaps apocryphally, with the phrase “less is more“, identified by many as the leitmotiv of Minimalism. After Mies, the influence of Minimalism is appreciable in a remarkable number of contemporary architects, from the Japanese Tadao Ando and SANAA to the Portuguese Álvaro Siza and Eduardo Souto de Moura. The influence of Minimalism has also been suggested, to a greater or lesser extent, in the literary works of Samuel Beckett (1906-1989), and in some musical compositions by John Cage (1912-1992).

Shortly before his death, Sol LeWitt, who as we have said is considered one of the great figures of Minimalism, said: “Minimalism wasn’t a real idea – it ended before it started”. Several contemporary examples, among them the Postminimalism of artists such as Richard Serra (b.1938), seem to disprove him. As Cedric VanEenoo wrote (“Minimalism in art and design: concept, influences, implications and perspectives”, 2011) “minimalism still exists despite the fact that it is pronounced dead from time to time (…) Minimalism is not only recognizable but visible on many fronts. The style once considered to be subversive has over time become acceptable, in part because it is so widespread in society at all levels.”

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: