Land Art

El legado de Robert Smithson

Reconcíliate, oh poeta, con tu universo, ¡esa es la única verdad!

¡Ja!

—el lenguaje está gastado

William Carlos Williams: «Paterson»

Robert Smithson: «Spiral Jetty», 1971 ·· Walter de Maria: «The Lightning Field», 1977. Fotografía de Retis, licencia C.C. 2.0

Tras finalizar sus estudios en la Art Students League y en la Escuela de Arte del Museo de Brooklyn de Nueva York, a finales de los años 50, el joven Robert Smithson (1938-1973) era un típico caso de artista joven que todavía no había encontrado su identidad. Hasta mediados de los 60, su obra dio extraños vaivenes entre la pintura religiosa y el erotismo más o menos explícito, probando brevemente el Pop Art que empezaba a dominar la escena artística americana. Como tantos otros artistas/creadores de la “generación beat”, realiza varios viajes en autostop por Estados Unidos y México, uno de ellos en 1957, el año de publicación de “En el camino” de Jack Kerouac. No obstante, la gran influencia literaria de Smithson no fue Kerouac, sino el poeta William Carlos Williams (1883-1963), que había sido su pediatra de niño, y con el que retomó contacto en 1958, tras concluir sus viajes. “Paterson”, el épico y complejo poema-libro de Williams, con su idea subyacente del hombre en comunión con el lugar que habita, parece fundamental en el desarrollo de la obra de madurez de Smithson, quien «describió provocativamente partes del ‘Paterson’ de Williams como ‘arte proto-conceptual’, al tiempo que recordaba sus propias conexiones con la región, sus exploraciones de niño en lugares mineros abandonados: ‘Supongo que la zona de Paterson es donde tuve gran parte de mi contacto con las canteras y creo que eso está en cierto modo incrustado en mi psique’«. (Clark Lunberry: «So Much Depends: Printed Matter, Dying Words, and the Entropic Poem», 2004)

Pero antes de llegar a sus obras de su (tristemente breve) madurez, a mediados de los 60 aparecería otra de las grandes influencias para Smithson: el Minimalismo, movimiento por el que el artista se sintió interesado hasta el punto de crear algunas obras que se podrían clasificar dentro de ese estilo. La relación de Smithson con el Minimalismo fue compleja. Al artista le atraía la negación minimalista del espacio y tiempo clásicos, escribiendo en 1966 que «en lugar de hacernos recordar el pasado como los antiguos monumentos, los nuevos monumentos parecen hacernos olvidar el futuro (…) [Dan] Flavin fabrica «monumentos instantáneos», (…) convierte el espacio de la galería en tiempo de la galería. (…) Un millón de años está contenido en un segundo, y sin embargo tendemos a olvidar el segundo tan pronto como sucede. La destrucción de Flavin del tiempo y el espacio clásicos se basa en una noción totalmente nueva de la estructura de la materia«. (Robert Smithson: «Entropy and the New Monuments«, 1966). No obstante, rápidamente empieza a rechazar la concepción clásica de la obra de arte como objeto autónomo, también presente en el Minimalismo. “Visitar un museo es ir de vacío en vacío”, escribe en 1967. “Los museos son tumbas, y parece como que todo se está transformando en un museo”.

En este sentido, la crítica de Smithson a los museos (describiéndolos como “tumbas”) no parece a primera vista innovadora, ya que ya en 1909 el Manifiesto Futurista de Tommaso Marinetti los describía como “cementerios”. Pero la crítica de Smithson no va enfocada tanto al tipo de obra expuesta, o a su alcance temporal, sino a la propia naturaleza del museo, como conjunto de obras descontextualizadas. A partir de 1967 explora esta idea en sus “Non-sites” (No-lugares), en las que elementos (piedras, tierra) de una zona específica son instalados en un museo como obra de arte autónoma. «El ‘non-site’ (…) es una imagen lógica tridimensional que es abstracta, pero que representa un sitio real en Nueva Jersey (…) Gracias a esta metáfora tridimensional, un sitio puede representar a otro que no se le parece, de ahí la idea de ‘non-site’” (Robert Smithson: «A Provisional Theory of Nonsites«, 1968), y al año siguiente publica el ensayo “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects”, donde, como resultado de la evolución artística de Smithson, la idea del Land Art aparece de forma explícita.

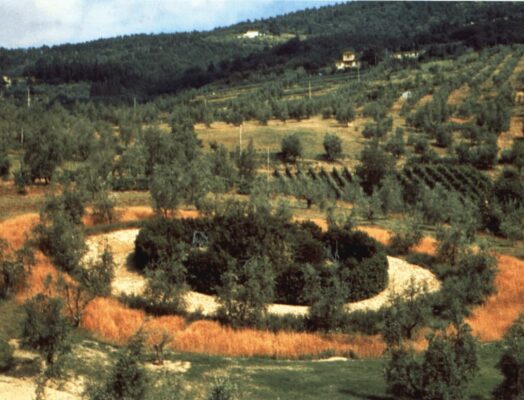

Alan Sonfist: «Circles of Time», 1986-89. Fotografía de Alan Sonfist, licencia C.C. 4.0 ·· Richard Long: «Full moon circle». Fotografía de Mikenorton, licencia C.C. 4.0

Ese mismo año, la Dwan Gallery de Nueva York presenta “Earthworks”, donde se documentan obras de Smithson, junto con artistas como Walter de Maria (1935-2013), Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) o Richard Long (n.1945). Estos mismos artistas volverían a exponer conjuntamente al año siguiente, en la exposición “Earth Art” organizada por el Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art. En estos dos años -1968 y 1969- se produce una rápida popularización del Land Art, cuyo ataque a la concepción tradicional de obra de arte autónoma era aplaudida por los artistas y admiradores del Arte Conceptual, y su acercamiento al medio natural fue bien acogido en una época en la que el ecologismo era cada vez más aceptado. Smithson, no obstante, fue en ocasiones crítico con el movimiento ecologista, al que acusó de “defender lo que él consideraba una estética ingenua que buscaba preservar y mantener lo que era fundamentalmente una naturaleza humanizada, construida según una concepción particular de la belleza” (Gary Shapiro: “Earthwards: Robert Smithson and Art After Babel”, 1995)

En la primavera de 1970, Smithson crea la que es probablemente la obra más conocida del Land Art, y en la que se pueden resumir las características claves del mismo. “Spiral Jetty” es una colosal espiral de 460 metros de largo, creada a base de materiales locales (basalto, cristales de sal, tierra), cuyo aspecto varía con el paso del tiempo, llegando en ocasiones a quedar completamente sumergida bajo el agua, para reaparecer en tiempos de sequía. Tras “Spiral Jetty” y “Broken Circle/Spiral Hill” (una obra en cierto modo similar a “Spiral Jetty” realizada en los Países Bajos en 1971), Smithson proyectó su intervención más ambiciosa (y jamás realizada), el “Bingham Canyon Reclamation Project” (1973), en la que convertía la mayor mina a cielo abierto del mundo en una colosal instalación “site-specific”. Ese mismo año, Smithson falleció en un accidente de avioneta en Texas.

Smithson fue la gran figura del Land Art, pero hubo otros muchos que contribuyeron al movimiento, entre ellos el ya mencionado Walter de Maria (1935-2013), autor de la colosal “The Lightning Field” en Nuevo Mexico. Alan Sonfist (n.1946), a veces considerado un precursor del Land Art por sus instalaciones urbanas en Nueva York, ha creado instalaciones “site-specific” desde los años 70 hasta bien entrado el siglo XXI, como su “Lost Falcon” de 2004. También activo durante décadas, el estilo de Richard Long (n.1945) puede considerarse a medio camino entre el Land Art y el Minimalismo.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: