Islamic Art

Geometries for an everlasting faith

What can ‘art’ mean in a culture where the primary organ of perception is not the eye or the ears, but the heart? It requires a shift from the visible to the sensible, in which attention is directed not outwardly toward the object, but inwardly, within the heart

Wendy M. K. Shaw: “What is ‘Islamic’ Art?: Between Religion and Perception”

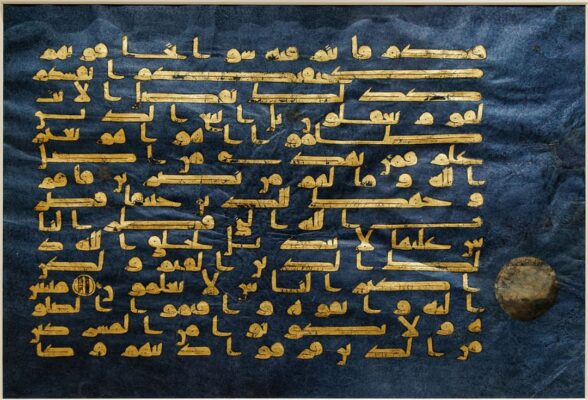

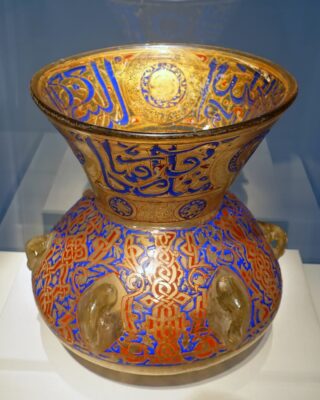

Folio from the Blue Qur’an, 9th –10th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art ·· Lamp, Egypt, c. 1360 AD. Freer Gallery of Art

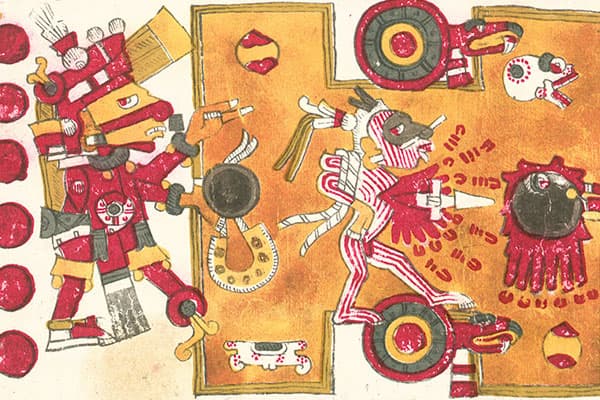

Although Islamic art spans a wide temporal (over a millennium) and geographical range (from West Africa to Southeast Asia), it has many stylistic features common to all times and places. In general, Islamic art does not focus on the concrete depiction of figures (forbidden according to some interpretations of the Qur’an), and makes use of geometric, floral or even abstract designs, which are present in all forms of artistic expression, from textiles to architectural elements.

There is some debate about the influence of early Christian art on the formation of Islamic art, although it is undisputed that in the early days of Islamic expansion, the conquerors were attracted to Byzantine works of art. “At the beginning of conquests, Muslims admired the art of the conquered Christian world, noing the brilliance of church decoration as a superior technique (…) The Byzantine mosaicists were brought, in order to decorate the mosque of Damascus and probably that of Medina. However, Muslims’ initial awe and admiration may raise rejection and contempt.” (Hee Sook Lee-Niiniona, “Islamic calligraphy & Muslim identity”, 2018). In its eastward expansion, Islamic art also borrowed elements from Sassanid art.

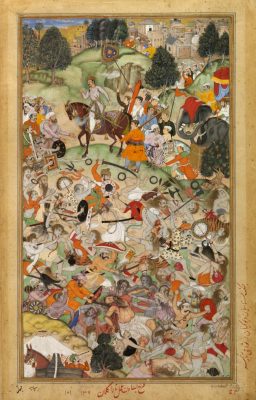

Among all forms of Islamic art, calligraphy is particularly important, to the point of being considered the “quintessence” of Islamic art (“Arabic script and the Art of Calligraphy”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art), and is manifested not only in manuscripts, but also in ceramics, tiles and even architectural elements. As for painting, the traditional form is the miniature, which flourished especially in Persia, from where it reached India during the Mughal Empire, and in Turkey during the Ottoman Empire.

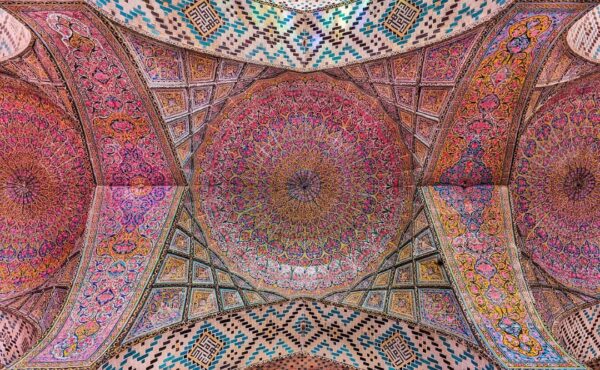

Basawan: “Battle of Thanesar”, 1590-1596. Miniature ·· Ceiling in the interior of the Nasir-ol-Molk Mosque, Iran, 1876-1888. Photo by Diego Delso.

Another of the most highly prized artistic techniques in Islamic art is glass, influenced by ancient Roman glass. In Islamic art, glass “follows two different developments: in Egypt, treat the rock crystal as a stone; in Syria, blowing glass, with results of great finesse and transparency” (Emilio de Santiago Simón, “The keys to the Islamic world, 622-1945”, 1991). Metalworks include figures of mythological animals, such as aquamaniles and the Pisa Griffin, probably created in al-Andalus.

Among the best-known forms of Islamic art are carpets, of which fabulous examples from Persia and Turkey have survived. However, their use was widespread in virtually all regions influenced by Islam. In the words of Dr. Rabah Saoud (“The Muslim carpet and the origin of carpeting”, 2004), “for the traditional Bedouin tribes of Arabia, Persia and Anatolia the carpet was the centre of their life”, being used as a makeshift tent, as a floor or as a curtain. But in addition, “with Islam, another significant value was added to the carpet, beng a furniture of Paradise mentioned numerous times in the Qur’an, for example in Surah 88”.

Islamic architecture show particularities mainly related to the place where the work of art was created. In the architecture of al-Andalus, for example, we find horseshoe arches borrowed from Visigothic buildings, while in India some elements were taken from syncretism. A characteristic feature of the most important Islamic buildings is their use of mosaics and tiling using brightly coloured tiles, probably influenced by Byzantine buildings.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: