Ancient and Classic Greece

In search of the ultimate beauty

Art takes nature as its model

Aristotle

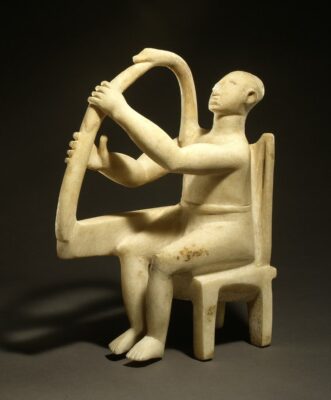

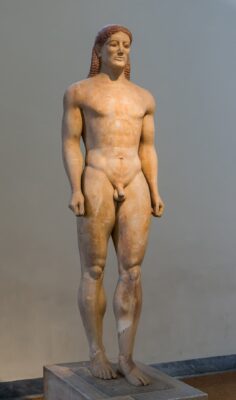

Images: Seated harp player, Cyclades Islands, c.2800-2700 BC. New York, Metropolitan Museum ·· Spring fresco, from Akrotiri, c.1600-1500 BC. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. ·· Kroisos Kouros, c.530 BC. National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Few would doubt that Greek Art, especially that created during the Classical and Hellenistic periods, constitutes one of the high points in the history of universal art. This is especially noticeable in sculpture, which combines a hitherto unattained naturalism with the search for ideal beauty, giving rise to artists such as Phidias, Praxiteles and Myron, whose works -usually known through Roman copies- are among the most iconic in the history of art, which can also be said of the Greek temples, such as the Parthenon or the now destroyed Temple of Artemis. Fewer works of painting -even through copies- have come down to us, although important examples on ceramics have survived. As in most chapters of history, this period of splendour was not limited to the artistic field, but art accompanied a period of exceptional progress in philosophy, culture and scientific knowledge. In a word, in civilisation.

But why did this era of wonders come about, and why did this region of islands and mountainous landscapes give birth, almost simultaneously from a historical perspective, to Plato and Phidias, Pythagoras and Praxiteles, Democritus and Polyclitus? For Carl Sagan, the Aegean region had the advantage of being at a crossroads of civilisations. “It was in the Eastern Mediterranean that African, Asian, and European civilizations, including the great cultures of Egypt and Mesopotamia, met and cross-fertilized in a vigorous and heady confrontation of prejudices, languages, ideas and gods.” (Carl Sagan: “Cosmos”, 1980).

As discussed in the chapter on Neolithic art in Europe, noteworthy works of art from the Middle Neolithic period have been found in the Thessaly region, but it is possible that the earliest masterpieces of Greek art are the marble figures of the Cycladic Islands, created from the 5th millennium BC onwards. These stylised figures, whose influence on the sculpture of modern artists is easy to see, “are the product of an imperfectly understood culture. Few settlements have been found, much of the evidence— including the marble figures—comes from graves, and scholars have not established the precise origin of the inhabitants” (Michael Norris: “Greek Art. From Prehistoric to Classical”, 2000).

In Crete, the Bronze Age saw the splendour of the Minoan Civilisation. From it, the palaces of Knossos and Akrotiri, though badly damaged, have provided some of the most admired works of art from the pre-Hellenic Greece, especially the fresco paintings. In the field of the arts, “the Cretans showed an admirable spirit of independence. They were the only European people who, under the influence of Egypt, tried to shake off the yoke of the artistic formulas of their neighbours, seeking fresh inspiration in the study of their own landscape. Through constant observation of everything that moved in their fields and in their waters, the artists of Crete managed to give a pulsating life to all their creations, with a novelty and a freshness that can only be equalled in the decorative art of the peoples of the Far East, the Chinese and the Japanese” (Antonio Blanco Freijeiro: “Greek Art”, 1956). The Minoan civilisation had a great influence on the art of the Mycenaean Civilisation.

From the Geometric Period of Greek art (900-700 BC), good examples of funerary pottery have survived. This period was followed by Archaic Greece, whose most recognisable characteristic is the so-called “Archaic smile” which is displayed on several of the sculptures of the period. It is possible that this distinctive feature “has originated in Sumerian, Akkadian and Egyptian free-standing sculpture, which precedes the more well-known archaic counterpart by over a millennium” (Emilie Charron: “Archaic Greek Sculpture and Its Foreign Influences”, 2016). In any case, the most important contribution of the Archaic period was the appearance of the Greek temple with the basic characteristics that would continue during the Classical and Hellenistic periods.

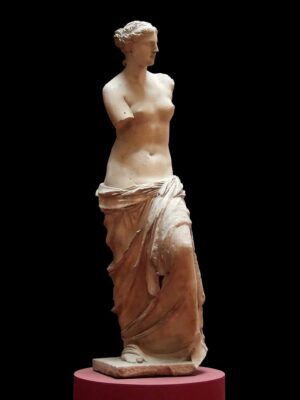

Images: The Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens, 447-438 BC. ·· Roman copy (2nd century) of the Discobolos of Myron, Munich Glyptothec. Photograph by MatthiasKabel ·· Figure of Aphrodite, known as Venus de Milo, c.130-100 B.C. Musée du Louvre. Photograph by Shawn Lipowski.

The change from the Archaic Period to the Classical Period (beginning around 450 BC) is particularly noticeable in sculpture, moving from the somewhat rigid and static style of the kouros to a more naturalistic style, a move usually associated with the advent of democracy and the consequent confidence in and admiration of the human being. “Although the classical style did not spring up immediately at the inception of democracy after 510 B.C., (…) it is difficult not to associate it, however indirectly with historical circumstances (…) Free of the magical associations of the East and permeated by the individuality of the artists, classical sculpture was based upon perception of changing visual phenomena. Its emergence was based on ceaseless experimentation with ever more lifelike renderings of the human form, which was almost its sole subject.” (Diana Buitron-Oliver: “The Greek Miracle: Classical Sculpture from the Dawn of Democracy”, 1992). The Classical Period saw the birth of the most celebrated sculptors of ancient Greece. Phidias, perhaps the most important of all, whose workshop produced the now destroyed Statue of Zeus at Olympia, one of the Wonders of the ancient world; Myron, creator of the Discobolus, perhaps the most famous of all Greek sculptures; and later Praxiteles, Scopas and Lysippus.

The art of the Hellenistic Period (from Alexander the Great to the principality of Augustus) has long been associated with a certain sense of decadence. However, it is more accurate to say that the characteristic of Hellenistic art is its heterodoxy, in comparison with the Classical Period, derived from contact with other cultures under the period of expansion initiated by Alexander. In the words of Professor Blanco Freijeiro, “the Greek of the city-state suddenly found himself a citizen of a vast territorial unit, sometimes encompassing peoples of different races and languages“. Faced with these new challenges, “Greek artists and writers sought to renegotiate the position of the Greek intellectual within the Hellenistic world“. (Alice Jessica Chapman: “The contemporary gaze in Hellenistic art and poetry”, 2015) Mark D. Stansbury-O’Donnell (“A History of Greek Art”, 2015) identifies as cultural characteristics of the Hellenistic Period its cosmopolitan character, its emphasis on individuality and the importance of theatricality. From the Hellenistic Period are works such as the Laocoön and his sons, the Venus de Milo, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, or the destroyed Colossus of Rhodes, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: