Gothic Art

And the wall became light

“The new world was beginning. White, limpid, joyous, clean, clear and without hesitations, the new world was opening up like a flower among the ruins. They left behind them all recognized ways of doing things, they turned their backs on all that. In a hundred years the marvel was accomplished and Europe was changed.

The cathedrals were white”.

Le Corbusier: “When the Cathedrals Were White”, 1934

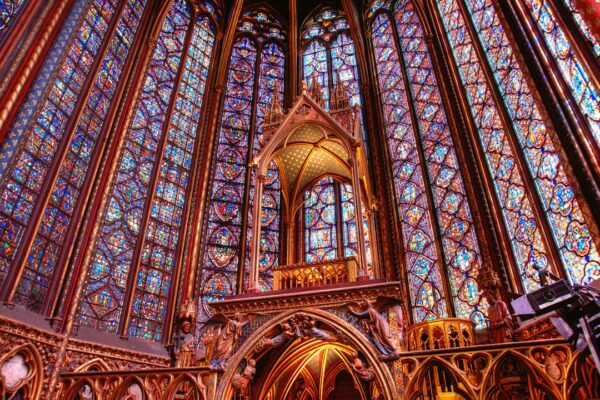

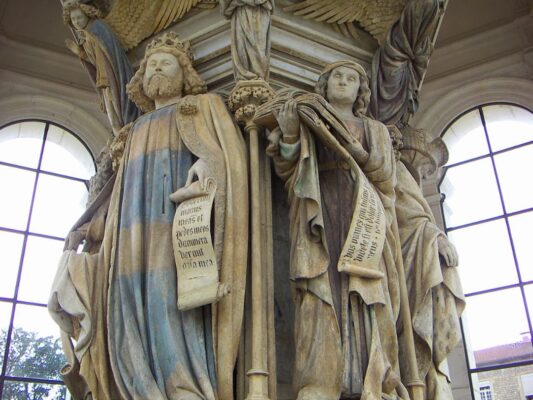

Images: Reims Cathedral (1211-1275). Photo by bodoklecksel ·· Interior of the Sainte Chapelle (1242-1248), Paris. Photo by Jean-Christophe Benoist ·· Claus Sluter’s “The Well of Moses”, 1395-1403

Like Romanesque art, Gothic art does not have a clear beginning and end, coexisting for a long time with its predecessor, and maintaining its preponderance in certain areas even as the Renaissance was making its way through Europe. And, like the Romanesque, the Gothic is a faithful reflection of its time. Whereas the order and rigidity of Romanesque was a reflection of feudal society, Gothic is a more urban style, at a time when cities became more important, with the emergence of universities and mercantile society. Of course, the Gothic remains a distinctly Christian style, but during the late Middle Ages religion is no longer the omnipresent and sole source of knowledge. With the Gothic “begins a doubt that creates an immature, insecure and hesitant phase. The Gothic lives under the divine theology but with potholes and doubts that the Romanesque did not have”. (Enrique Valdearcos, “Gothic Art”, 2007).

Gothic architecture, of which cathedrals are particularly representative, is characterised by its height and even more so by the lightness of its enclosures. Various constructive solutions, especially the ribbed vault, allow the massive walls typical of Romanesque architecture to become large openings through which light -the true protagonist of Gothic architecture- floods the interior spaces. Polychrome stained glass windows, one of the symbols of Gothic architecture, reach spectacular heights in buildings such as the Sainte-Chapelle (1242-1248) in Paris.

Logically, there are differences in style, and even in time frame, in the Gothic art of different areas. First of all, it should be noted that the transition from the massiveness of Romanesque to the lightness and luminosity of Gothic was by no means sudden, there being precedents such as Cistercian art, often considered a “transitional style” between Romanesque and Gothic. At the end of the 12th century, some buildings in northern France such as the Basilica of Saint-Denis or the famous Notre-Dame de Paris can already be considered fully Gothic, a style which soon passed to England with the reconstruction of the Canterbury Cathedral. The full splendour of Gothic architecture came in the mid-13th century with the Rayonnant (or Radiant Gothic) style, with buildings such as the aforementioned Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, Chartres Cathedral (begun in the 12th century but completed in the following century), Rheims Cathedral and the now destroyed Saint-Nicaise de Reims. Gothic arrived somewhat later in southern Europe, leaving examples such as Leon Cathedral and the Doge’s Palace in Venice.

In sculpture, architectural relief continued to be important, with notable examples like those in the cathedrals of Rheims and Notre-Dame. However, in comparison with Romanesque sculpture, Gothic sculpture gained independence from architecture, with great examples of free-standing sculptures appearing. Among the foremost sculptors of the Gothic era were Nicola Pisano (12th century) in Italy and Claus Sluter (14th century) in northern Europe.

Giotto di Bondone: “The Kiss of Judas”, fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel, 1304-05 ·· Jan van Eyck: “Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife (The Arnolfini Marriage)”, 1434. London, National Gallery

Despite the importance of architecture, it is possibly in painting that the transition from Romanesque to Gothic is most noticeable. In contrast to the hieratic and rigid style of Romanesque painting, Gothic painting gained in creative freedom, no longer limited to monastic spaces, but with the appearance of patronage and collecting, a new clientele appeared. “Individual patronage of the arts meant the emergence of a new concept in the history of art: taste. But also, the consolidation of painting as an autonomous discipline, less costly than architectural foundations and sculptural works, and more suitable than the latter for domestic spaces” (“Historia Universal de la Pintura”, Volume 2, published by Espasa Calpe, 1997).

This new type of demand led to the appearance of panel painting, easy to transport and suitable for both religious and private spaces. In Italy, artists such as Cimabue and Duccio, departing from Byzantine iconography, began to adopt a more naturalistic style. Special mention should be made of Giotto (Giotto di Bondone, c.1266-1337), one of the great renovators of Western painting, whose achievements would not be surpassed until the arrival of the great masters of the Quattrocento. The style of the Italian masters of the Trecento, such as those mentioned above and Simone Martini, spread throughout Europe, giving rise to the so-called International Gothic Style.

In North Europe, the work of the Early Netherlandish painters, from Jan van Eyck or Roger van der Weyden to Hieronymus Bosch, coincides chronologically with the beginning of the Renaissance, although its style is heir to the Gothic miniatures. In the latter field, Northern European artists produced masterpieces such as the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry by the Limbourg Brothers.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: