Fauvism

The power of pure painting

But here one finds, above all in the work of Matisse paintings outside every contingency, painting in itself, the act of pure painting. (…) Finally all the factors of representation and of feeling are excluded from the work of art. (…) Here is, in fact, a search for the absolute. Yet, strange contradiction, this absolute is limited by the one thing in the world that is most relative: individual emotion.”

Maurice Denis, 1905

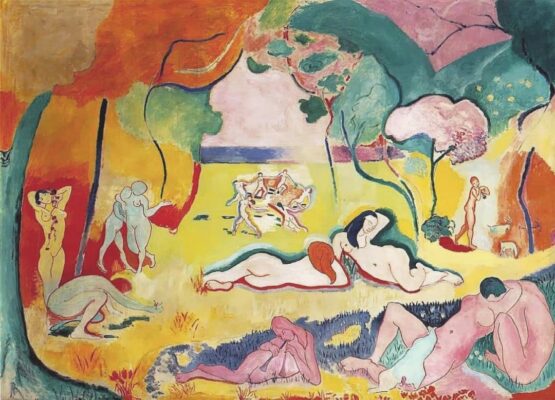

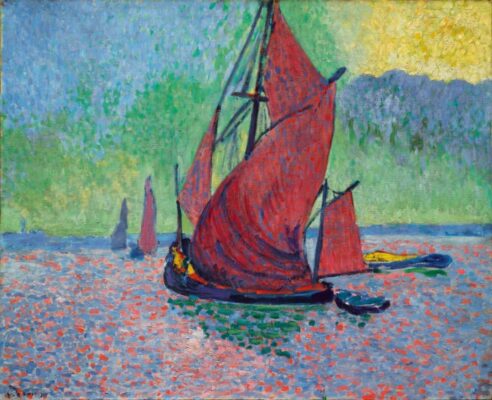

Images: Henri Matisse: ” Bonheur de Vivre (Joy of Life)”, 1905-06. Oil on canvas. Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia ·· André Derain: “Les voiles rouges”, 1906. Oil on canvas. Private collection

The seed of Impressionism, as we have seen in previous chapters, was planted in the so-called “Salon des Refusés” -a somewhat derogatory name given to the space reserved for those artists rejected by the elitist Paris Salon- in 1863. Its lack of success meant that, despite the requests of several artists, there was no second edition of this “alternative salon”, but eleven years later the Impressionist group had achieved enough unity to organize on its own the First Impressionist Exhibition, which in reality was nothing more than a monothematic “Salon des Refusés”. Despite the initial rejection, in the early years of the twentieth century Impressionism had already achieved significant recognition, which in 1903 led the architect and art critic Frantz Jourdain to think that it might be a good idea to organize a new alternative Salon, dedicated to young artists, in the hope that they would achieve, in the medium or long term, a recognition similar to that of Impressionism.

Jourdain’s proposal had several interesting ideas. First of all, he organized his Salon in autumn -calling it, in fact, Salon d’Automne-, so it would not coincide with the official salons held in spring. He also encouraged artists to exhibit paintings created au plein air during the summer, and opened the doors to new artistic disciplines, such as photography. Seen in retrospect, knowing how fruitful -from an artistic point of view- the early years of the 20th century were, it was only a matter of time before the Salon d’Automne saw the birth of a group, a style, a movement that would change the history of art. And that moment arrived at the third edition of the Salon, in 1905.

At that edition, a group of young artists, including Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Kees van Dongen and Albert Marquet, exhibited a group of paintings that stood out for their intense and seemingly arbitrary use of color. The works, which were hung in the same room as Albert Marque’s Renaissance-looking sculptures, led the critic Louis Vauxcelles to describe the scene as “Donatello chez les fauves” (Donatello among the wild beasts), from which the name of the movement was derived. An alternative, more recent theory about the origin of the name refers to Henri Rousseau‘s painting, “Hungry Lion Attacking an Antelope,” also exhibited at the Salon. Be that as it may, Fauvism, sometimes considered the first avant-garde, was already born.

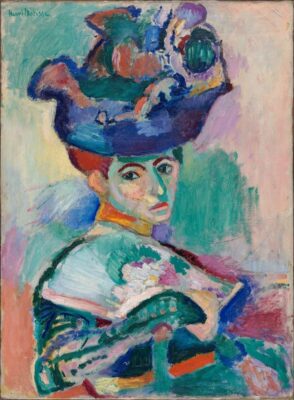

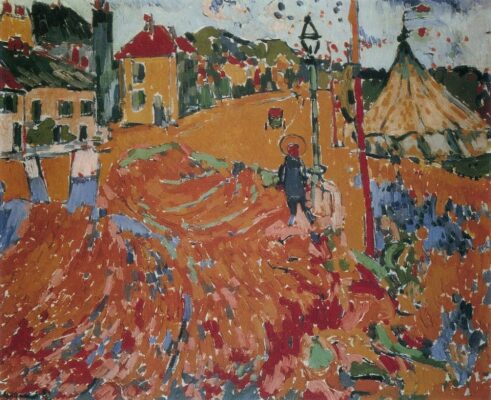

Images: Henri Matisse, “La femme au chapeau”, 1905. Oil on canvas, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art ·· Maurice de Vlaminck, “Circus”, 1906. Oil on canvas, Beyeler Foundation, basel.

The influence of several post-impressionist painters on Fauvism is immediately noticeable, both from the pointillism of Seurat and Signac and from the last years of Van Gogh. In this sense “Fauvism was a synthetic movement, seeking to use and to encompass the methods of the immediate past. (…) The first true Fauvist style, largely the work of Matisse and Derain in 1905 (…) combined features derived from Seurat and van Gogh, scumbled, scrubbed brushwork, and arbitrary color divisions reminiscent of Cezanne” (John Elderfield: “The ‘wild beasts’ : Fauvism and its affinities”, 1976).

The most prominent of the Fauvist painters was Henri Matisse (1869-1954), whose “La femme au chapeau” (1905, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) drew the most criticism at the 1905 Salon. Matisse was also the creator of the greatest Fauvist masterpiece, the monumental “Le bonheur de vivre” (1906, Barnes Foundation), presented at the 1906 “Salon des Indépendants“, which inspired Picasso to paint his famous “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907), often considered a dark and scathing answer to Matisse’s painting. The second great figure of Fauvism is André Derain (1880-1954), who worked with Matisse in Collioure during the summer of 1905, where the Occitan light brought out Fauvism, thanks to “the affirmation and use of pure colors, the elimination of the tonal gradation typical of pointillism, the luminosity of each and every one of the colors, of each and every one of the brushstrokes” (Valeriano Bozal: “Los orígenes del arte del siglo XX”, 1993). Years earlier, Derain had shared a studio with Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958), often considered the third part of the “trinity” of the Fauvist masters.

Fauvism was not only the first of the avant-garde, but also the shortest. It was presented in 1905, and began its decline the following year, and by the end of the decade it had been overshadowed by the more vigorous avant-gardes, such as Cubism. In the words of John Elderfield “Cubist painters considered Fauvism an extension of the Impressionist tradition, the last obstacle they had to over come to create something that was entirely new.” In the turbulent first decade of the twentieth century, art continued its metamorphosis and the wild beasts themselves were devoured by the avant-gardes they had helped to create.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: