Expressionism and New Objectivity

The narrators of an unrested zeitgeist

Art today is moving in directions of which our forebears had no inkling; the Horsemen of the Apocalypse are heard galloping through the air; artistic excitement can be felt all over Europe

Franz Marc: Der Blaue Reiter Manifesto

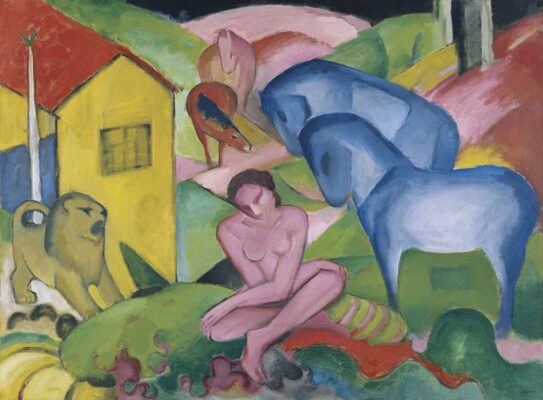

Franz Marc: “The Dream”, 1912. Oil on canvas. Madrid, Museo Thyssen ·· Still from the movie Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari, directed by Robert Wiene (1920)

In general, it is not excessively difficult to define temporally the avant-garde movements of the first half of the 20th century (Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism…), which combined their short duration with relatively clear start and end dates. A clear exception to this is Expressionism, a heterodox movement, whose name -which only came into more or less widespread use after 1910, when it was popularized by Antonin Matějček and Herwarth Walden- refers to art based on subjectivity and emotion as opposed to purely rational and objective representation, an art born of the artist’s inner gaze, not of the objective study of reality; on the emotional dominating the rational.

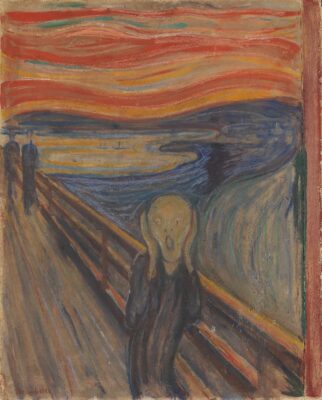

But if we simply accept this definition, where do we place the beginning of Expressionism? In 1905, in Dresden, with the foundation of the group “Die Brücke” (The Bridge)? Or do we admit as “expressionist” the famous “The Scream” by Edvard Munch, whose first version dates from 1893? Going back even further in time, it is difficult not to identify clearly expressionist elements in Vincent van Gogh‘s paintings, especially in his works between Arles and Auvers (1888-1890). Many authors have also pointed to late Renaissance artists such as Matthias Grünewald (1470-1528) or El Greco (1541-1614) as clear precedents of expressionism, and even -adopting a more lax view, but without leaving the Western pictorial tradition- we could identify expressionist elements in the Crucified Christ of Giunta Pisano (13th century).

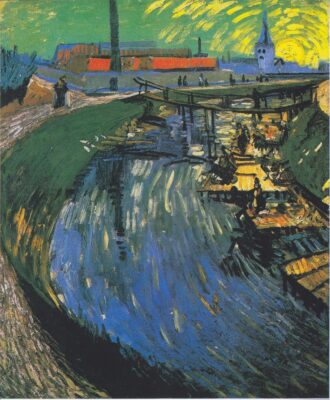

Antecedents of German Expressionism: Vincent van Gogh: “Washerwomen at ‘La Roubine du Roi'”, 1888. Oil on canvas. Private collection ·· Edvard Munch: “The Scream”, 1893. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Norway.

Art historians usually limit the definition of Expressionism to the movement that originated in Germany in the first decade of the 20th century, coinciding temporally with Fauvism and Cubism in France. Like almost all avant-garde movements, Expressionism is indebted to the experiments of the post-impressionists. For E.H. Gombrich (“History of Art”, 1950), “Cézanne’s solution led, finally, to the Cubism that emerged in France; Van Gogh’s, to Expressionism, which found its main representatives in Germany“. In this sense, expressionism is “a typically Germanic and ‘romantic’ attitude as opposed to the ‘classicism’ of the fauves and cubists” (Historia del Arte, Salvat Editores, Volume 9).

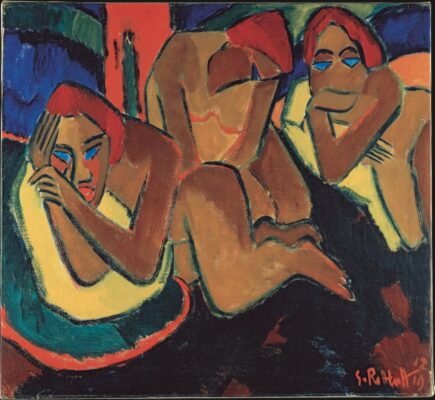

In 1905 the group “Die Brücke” (The Bridge) was founded in Dresden by the painters and illustrators Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884-1976) and Erich Heckel (1883-1970), as well as the architect Fritz Bleyl (1880-1966), who left the group two years later. “Die Brücke” generally constituted a very cohesive group, based on the collaboration between artists, and on the simultaneous admiration for primitivism and contempt for the bourgeoisie. They invited all young artists to join the group, regardless of their style or nationality, noting in the Founding Manifesto itself (written by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner) that “everyone who reproduces, directly and without illusion, whatever he senses the urge to create, belongs to us.” They experimented with woodcut, and their youthful impetus opened the door for important painters such as Emil Nolde (1867-1956), Max Hermann Pechstein (1881-1955) and Otto Müller (1874-1930) to join the group, but there was also a lack of leadership, especially when Kirchner moved to Berlin in 1911. Some time after the breakup of the group with the outbreak of World War I, Erich Heckel himself admitted that “what we [Brücke-artists] had to remove ourselves from [the German bourgeois mores] was clear; where we were heading was certainly less clear”.

Die Brücke · Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, “In the Kiosko”, 1912. Oil on canvas. Staedel Museum ·· Der Blaue Reiter · Wassily Kandinsky , “Composition IV”, 1911. Oil on canvas. Kunstsammlung Nordhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf

In the same year that Ernst Ludwig Kirchner moved to Berlin, precipitating the dissolution of “Die Brücke”, the group “Der Blaue Reiter” (The Blue Rider) was founded in Munich, led by Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and Franz Marc (1880-1916), who were later joined by artists such as August Macke (1887-1914), Paul Klee (1879-1940), Gabriele Münter (1877-1962) and Lyonel Feininger (1871-1956). They were, generally speaking, a less impetuous and more cosmopolitan group than “Die Brücke”, which translated into a less “wild” and more lyrical expressionism, a characteristic accentuated by the interest of several of its protagonists in music. “The affinity between music and painting for Kandinsky ‘is the starting point of the path by which painting, with the help of its own means, will develop into art in the abstract sense’. Paradoxically, the most abstract of the arts turns out to be for them the most attached to reality” (María Santos García Felguera: “Las vanguardias históricas”, 1993). Thus, between 1910 and 1913, Kandinsky created seven large works, which he called simply “Compositions“, which illustrate by themselves the evolution of Kandinsky’s style from expressionism to pure abstraction.

On the other hand, Expressionism was one of the first avant-garde movements to show a real interest in cinema, an interest that multiplied after the end of the First World War. Thus appeared “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” (1920), directed by Robert Wiene, and “Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens” (1922), by F.W. Murnau, perhaps the first two masterpieces of the horror genre, and culminating in 1927 with “Metropolis” by Fritz Lang, a masterwork that brings together elements of Expressionism and Futurism.

After World War I, European art began to reject radical avant-garde movements such as Cubism, Futurism or Expressionism, a trend known as Return to Order. As a direct criticism of Expressionism, the so-called New Objectivity emerged, a name that comes from an exhibition at the Kunsthaus in Mannheim in 1925. The painters of the New Objectivity recovered the precision, the rational and often sarcastic look towards the social reality that they lived in a Weimar Republic that was gradually entering totalitarianism.

George Grosz: “Metropolis”, 1916-17. Oil on canvas. Madrid, Museo Thyssen ·· Max Beckmann: “Descent from the Cross”, 1917. Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art, New York

Perhaps the most outstanding of the artists of this New Objectivity was a painter who never really wanted to be considered as part of any movement: Max Beckmann (1884-1950) did not completely adopt the characteristics of Expressionism, but neither did he reject them with such intensity as to be considered a clear opponent of it. He was an individualistic personality, manifested in his interest in self-portraiture, who used the formal expressiveness of Expressionism and the biting spirit of the New Objectivity to capture in his paintings the traumas he carried with him from his service in the First World War.

The trauma of the War is also present in the work of Otto Dix (1891-1969), the most acid and stark critic of German society of his time. “I had the feeling that there was a dimension of reality that had not been dealt with in art: the dimension of ugliness,” he once declared. Dix depicted the horror of war (“the work of the devil!” as he wrote in his war diary) in his works “The Trench” and “War Cripples,” now lost and possibly destroyed during World War II. George Grosz (1893-1959) managed to avoid suffering first-hand the traumas of war, and it was precisely during the war years that he produced his most interesting works, urban views that take on elements of Futurism such as “Metropolis” (1916-17) and “The Funeral of Oskar Panizza” (1917-18).

As it seems logical, this New Objectivity also felt interest in photography, photography, a field in which the figures of August Sander (1876-1964) and Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) stood out.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: