Etruscan Art

Before the Empire

“To the Etruscan, all was alive: the whole universe lived: and the business of man was himself to live amid it all. He had to draw life into himself, out of the wandering huge vitalities of the world”

D.H. Lawrence: “Etruscan Places”

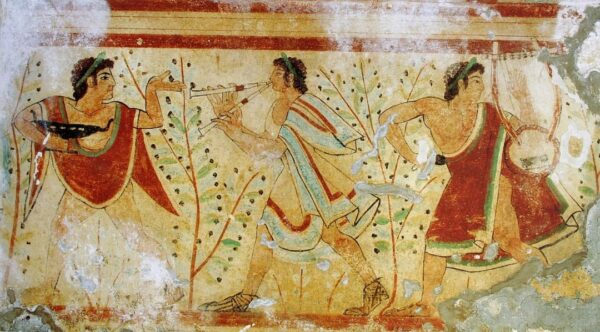

Images: Sarcophagus of the spouses, c.530-500 BC, Etruscan National Museum. Photo by Sailko ·· Chimera of Arezzo, c. 400 BC, Etruscan National Museum ·· Dancers and musicians, c.475 BC, from the Tomb of the Leopards, Monterozzi necropolis.

The Etruscan civilisation developed in the central part of what is now Italy (mainly the regions of Tuscany, Umbria and northern Lazio), appearing between the 10th and 9th centuries BC, and being assimilated by the rising Roman civilisation between the 4th and 1st centuries BC. They created a Greek-influenced art, of which a good number of funerary works have survived.

As for the “identity” and “independence” of Etruscan art, there are somewhat conflicting opinions. On the one hand, several scholars, while recognising the originality of some Etruscan art, point to a clear continuity with Greek or Phoenician art. For example, Miguel Ángel Elvira and Antonio Blanco Freijeiro asked “why did Etruscan art not reach a level of absolute independence in its plastic language? What made Etruscan artists and patrons content themselves in many fields with styles created hundreds of leagues away from Etruria, in Phoenicia and, above all, in Greece” (“Etruria y Roma republicana”, 1989). In contrast, Jocelyn Penny Small, in her publication “Looking at Etruscan Art in the Meadows Museum” (2009) states that “no one questions the idea that the Etruscans had a distinct culture. (…) There is a consensus that Etruscans did produce objects that can be called Etruscans for something like 800 years. (…) They made objects that were never made by Greeks, such as biconical urns“.

In sculpture, the Etruscans used mainly bronze and terracotta, the latter material being used in the most famous masterpieces of Etruscan art. The Apollo of Veii (c.510-500 BC, National Etruscan Museum, Rome) is a life-size statue attributed to Vulca, the sculptor of whom Pliny the Elder said that his works were ‘more admired than gold’. The Sarcophagus of the Spouses, also on display in the National Etruscan Museum, and the Sarcophagus of Cerveteri (Louvre Museum), were created, like the Apollo of Veyes, azt the end of the 6th century BC, and some historians have proposed that they may be the work of the same artist. The Sarcophagus of Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa, now in the British Museum, is one of the last masterpieces of Etruscan art, showing Roman influences. In bronze, the great masterpiece of Etruscan art is the Chimera of Arezzo, created around 400 BC.

Also remarkable is the Etruscan wall painting, which has survived on the walls of several tombs, such as the Tomb of the Leopards or the Tomb of the Triclinium. As Stephan Steingr (“Etruscan and Greek Tomb Painting in Italy”) points out, Etruscan painting constitutes the first chapter in the important history of Italian painting. Moreover, the influence of Greek art is particularly noticeable in Etruscan vase painting.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: