Dada

The nihilist rupture

Freedom: Dada Dada Dada, a roaring of tense colors, and interlacing of opposites and of all contradictions, grotesques, inconsistencies: LIFE

Tristan Tzara: Dada Manifesto, 1918

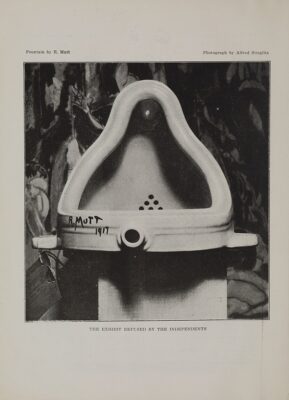

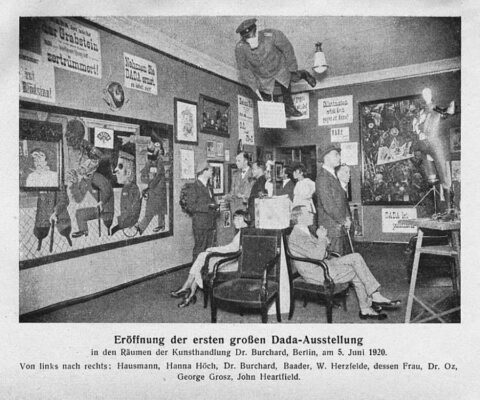

Marcel Duchamp: “Fountain” reproduced in “Blind man”, 1917 — Opening of the first Dada exhibition: June 5, 1920. including a figure of a German officer hanging from the ceiling with a pig’s head.

In the chapter devoted to Expressionism and New Objectivity, it was pointed out that after the First World War European art began to question the more radical avant-garde movements, such as Cubism and Expressionism, and adopted a critical attitude towards them. In general, this criticism led to what has come to be known as the “Return to Order”, the recovery of a less radical art and even the return to a neoclassical language, as in the case of Picasso. But there was another critique, not directed at the “how”, but at the very nature of art, a critique that was not really a critique but a negation, a sarcastic attitude, an indifferent gaze, an almost nihilistic thinking. The death of the concept of artist, the celebration of anti-art: Dada.

It was the German poet Hugo Ball (1886-1927) who founded Dada (or Dadaism) in Zurich in 1916, and he was soon joined by the young and versatile Tristan Tzara (1896-1963), the true soul of Dadaism. Ball and Tzara published their respective Dada Manifestos in 1916 and 1918, in which they defined Dada as “Dada is the world soul, dada is the pawnshop. Dada is the world’s best lily-milk soap. Dada Mr Rubiner, dada Mr Korrodi. Dada Mr Anastasius Lilienstein” (Ball) and “Dada Means Nothing (…) Freedom: Dada Dada Dada, a roaring of tense colors, and interlacing of opposites and of all contradictions, grotesques, inconsistencies: LIFE” (Tzara). Although at first glance Dada seems simply a joke, a vulgar joke (and perhaps that is the appearance that the Dadaists pursued), its founders were intellectuals possessed of an immense culture. Hugo Ball was a “student of Nietzsche’s work; stage manager and playwright for the Expressionist theatre; left-wing journalist; vaudeville pianist; poet; novelist; author of works on Bakunin, the German Intelligentsia, early Christianity, and the writings of Hermann Hesse; convert to Catholicism, he seemed, at one time or another, to have touched on nearly all the political and artistic preoccupations of the age” (Paul Auster: “Dada bones”, 2005). Tzara was a talented poet who edited, at the age of sixteen, a magazine that gave voice to numerous symbolist authors. But, in the face of the horror of World War I, intellectualism and culture lose their meaning. “A millenary culture disintegrates (…). The meaning of the world has collapsed,” wrote Ball during the war. In the face of the unreason of war, artistic irrationality is for them the only appropriate response.

After Tzara and Ball came those who would bring Dada into the visual arts. The most important of these was Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), one of the leading figures of avant-garde art, omnipresent in the major radical art movements of the 20th century, who had already participated in Cubism, and whose “Fountain” (1917) and “L.H.O.O.Q.” (1919) can be considered the visual Dada Manifestos. Further contributions to visual Dadaism came from Jean Arp (born Hans Peter Wilhelm Arp, 1886-1966) and Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948).

In many ways, to include Dadaism within a section of artistic styles or movements is something of an oxymoron. But their attitude of absolute rejection of the foundations of Western art, their questioning of any hitherto accepted rules, influenced the most important art movement of the inter-war period –Surrealism– while its direct attack on the conception of the artistic object would be continued, already in the midst of Postmodernism, by the artists of Conceptual Art and Minimalism. Paradoxically, the Dadaists, the artists who renounced art, would involuntarily but irremediably mark the course of 20th century art.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: