Cubism and Futurism

Breaking with Cartesian space

Futurism and Cubism are comparable in importance to the invention of perspective, for which they substituted a new concept of space. All subsequent movements were latent in them or brought about by them.

Gino Severini

Cubism: Georges Braque: “La guitare (La Mandore)”, 1909-10. Oil on canvas, Tate Modern, London ·· Pablo Picasso: “Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier)”, 1910. Oil on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, New York

In 1907, working in his modest studio in the Bateau-Lavoir, Pablo Picasso painted a work of monumental dimensions, then entitled “The Brothel of Avignon“, with which he baffled friends and rivals, including many avant-garde artists already accustomed to experimentation and innovation. In “The Brothel of Avignon” (which, as many will have deduced, is the work now known by the less controversial name of “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”) there is no background or foreground, no trace of perspective, and the foreshortening of the five female characters makes it impossible to identify a single point of view, a sensation heightened by the total absence of light and shadow. Although the women’s faces are clearly indebted to the African art that Picasso had admired at the Trocadero that same year, the painting’s influences are complex, including the late works of Cézanne (his “Great Bathers” and the late views of the Sainte-Victoire mountain), Matisse’s “The Joy of Life”, and even El Greco’s “Vision of the Apocalypse”, which Picasso had admired in the studio of the painter Ignacio Zuloaga.

As is often the case with innovative works, the painting was not well received initially, even -as has been mentioned- among avant-garde artists. But Georges Braque, a young painter who had hitherto moved between Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, overcame his initial misgivings and, taking an interest in the work and the possibilities it opened up, began to work with Picasso. This joint work by Picasso and Braque gave rise to Cubism, the most decisive and innovative of the avant-garde movements, the one that definitively broke with the spatial conception present in Western painting from the Renaissance. Previous movements, from Impressionism to Fauvism, had made important advances in the study of the possibilities of painting, but “despite the arbitrariness of colour [in Fauvism], there was some degree of identity between the painted image and the image that the camera would have offered when confronted with the same subject. Cubism attacked this conception in a systematic way and has therefore been considered one of the most revolutionary artistic movements in the entire history of Western art” (Juan Antonio Ramírez: “Las Vanguardias Históricas: del Cubismo al Surrelismo”, 1996).

In its first phase, the so-called analytical cubism (as it would later be called by the painter Juan Gris) makes clear some of the points already sketched in “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon“. The multiplicity of points of view, the almost monochrome composition, now totally devoid of perspective. Picasso and Braque were joined by other painters such as Fernand Léger, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes and Robert Delaunay, who presented their works at the Salon des Indépendants in 1911, to little critical acclaim. That same year the Spanish painter Juan Gris joined Cubism. On the other hand, between 1909 and 1910 Picasso created “Head of a Woman (Fernande)“, considered the first Cubist sculpture. In this field, the influences of “primitive” art (from the marble figures of the Cyclades Islands to the sculptures created by Gauguin in Tahiti) are even more noticeable than in painting.

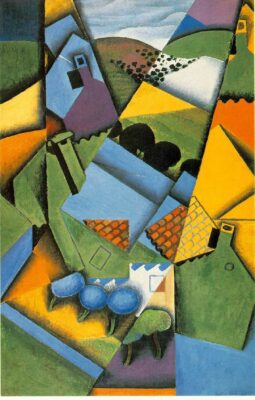

Juan Gris: “Landscape with house at Ceret”, 1913. Oil on canvas. Private collection ·· Fernand Léger: “La Ville”, 1910. Oil on canvas. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Analytical Cubism was possibly the purest form of Cubism, but although the canvases were the result of a complex analysis of forms and a detailed study of composition, it was often hermetic and almost incomprehensible to the viewer. From 1911 onwards, Picasso and Braque began to add figurative elements to the works, often using the Papier Collé technique. At the same time, the rather monochrome tones gave way to a more intense use of colours, sometimes seeking contrast between them as a compositional element, which was rejected by Analytical Cubism. This marked the beginning of a second phase of Cubism, known as Synthetic Cubism, whose development would last until the outbreak of the First World War. During this stage, Marcel Duchamp, whose “Nu descendant un escalier n° 2” combines elements of Cubism and Futurism -which will be discussed later- made a brief but intense contribution.

From 1914 onwards Cubism became increasingly popular among young artists, with figures such as Maria Blanchard and Diego Rivera joining the movement, and even the Japanese Tetsugorō Yorozu, one of the first to exhibit Cubist works in Asia; but it lost the experimental impetus that had been the driving force behind the early Analytical Cubism of Picasso and Braque. In the years following the First World War, it was the painters Juan Gris and Fernand Léger and the sculptor Alexander Archipenko who made the last notable contributions to the development of Cubism.

Futurism: Umberto Boccioni: “The City Rises”, 1910. Oil on canvas. New York, MoMA ·· Giacomo Balla: “Abstract Speed + Sound”, 1913. Oil on millboard. Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

So far we have noted the different forms that Cubism took during the approximately ten years of its evolution. However, at the same time as Picasso and Braque were working on the development of analytical Cubism, a group of Italian artists and intellectuals, largely influenced by the experiments of early Cubism, gave birth to Cubism’s impetuous and irreverent little brother, Futurism. While Cubism can only be seen as a purely artistic movement, Futurism is in fact a radical philosophical doctrine that manifests itself in art: absolute contempt for tradition and the past world, and the glorification of the modern world -even its (usually considered) negative characteristics such as violence or dehumanisation- in the face of the decadent past. In this sense, Futurism “upheld violence as good in itself, the value of war as a hygienic purge, the beauty of machinery, the glories of the ‘dangerous life’, blind patriotism, and the enthusiastic acceptance of modern civilization“. (Alfred H. Barr Jr.: “Cubism and Abstract Art“, 1936).

“A speeding automobile is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace“, wrote Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in the first Futurist Manifesto of 1909, in which museums were described as “cemeteries“. “Destroy the cult of the past, the obsession of the antique”. “Consider art critics as useless and noxious”. “Take and glorify the life of today, incessantly and tumultuously transformed by the triumphs of science”, the Futurist Painting Manifesto, published the following year, encouraged. What art emerged in response to these incendiary proclamations? One obsessed with movement, with technology, one that turns the automobile and industry into its muses. One of the first Futurist masterpieces, Umberto Boccioni‘s “The City Rises” (1910), glorifies the construction of the contemporary city, its chimneys, the almost violent effort of the construction workers. Even more than in the case of Cubism, the Futurists were interested in sculpture, a field in which Boccioni himself created “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space“, possibly the great masterpiece of Futurist sculpture.

Futurism: Umberto Boccioni: “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space”, 1913. Bronze. New York, MoMA ·· Antonio Sant’Elia: Design of a building with external elevators, 1914

Although Marinetti is considered the founder and most important theoretician of Futurism, Boccioni was arguably the movement’s main driving force. Other leading figures of Futurism were the painters Carlo Carrà and Gino Severini, and the painter and poet Giacomo Balla, whose “Abstract Speed + Sound” (1913-14) can be considered the culmination of Futurist artistic ideas. Outside Italy, some Russian artists, such as Natalia Goncharova, made interesting contributions to Futurism. In the field of architecture, Futurism created projects and sketches, but very few built works. The most famous Futurist architect is Antonio Sant’Elia, whose drawings served as inspiration for projects by later architects such as Helmut Jahn, as well as for film like “Metropolis” (1929) and “Blade Runner” (1982).

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: