Chinese Painting

Misty mountains, streams of ink

“Outside, the fog has lifted, the dark mountains have faded, the murmur of the rushing River resonates in your head, and that is enough.”

Gao Xingjian, “Soul Mountain”

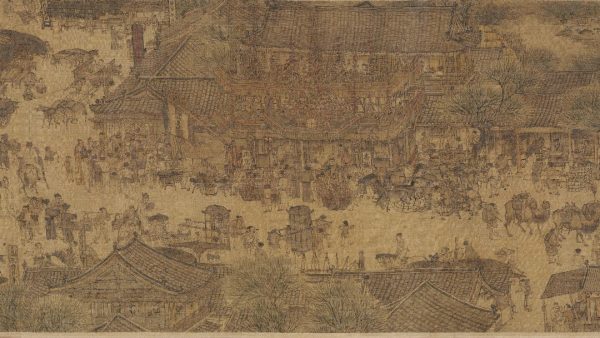

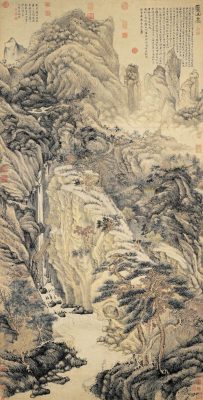

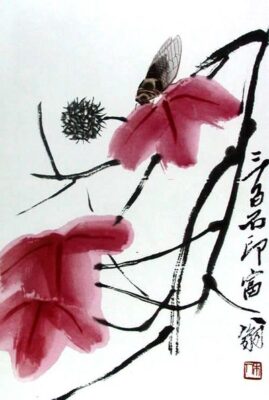

Images: Gu Kaizhi: “Nymph on the Luo River” (detail) 4th century ·· Zhang Zeduan: “Qingming Festival by the River”, 12th century ·· Shen Zhou : “Lofty Mount Lu”, 1467 ·· Qi Baishi (1864-1957): Painting of a Cicada

When studying the importance of painting and calligraphy in Chinese art, attention must be paid not only to their long and continuous tradition (more than two millennia), but also to the status that Chinese culture has historically reserved for them. As Max Loehr (“The Question of Individualism in Chinese Art”, 1961) explains, in the Chinese tradition only painting and calligraphy were considered to be disciplines of artistic significance, while other artworks (sculpture, ceramics) were considered the work of craftsmen, whose names and lives were rarely recorded.

Unlike in the Western tradition, where landscape painting was for centuries relegated to the background of religious or mythological scenes, not becoming a truly appreciated genre until the 17th century, in China landscape painting was regarded as the noblest form of painting. As early as in the paintings of Gu Kaizhi (“Nymph on the Luo River”, 4th century), several of the traditional aspects of Chinese landscape painting can be seen, such as the high peaks and the use of emptiness as a compositional element. In the 6th century, Xie He established the six principles of Chinese painting, which were by then considered to be part of the tradition.

During the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Chinese painting reached one of its zeniths. Zhang Zeduan‘s “Qingming Festival by the River”, sometimes considered the most important masterpiece of Chinese painting, dates from the early 12th century. Ma Yuan and Xia Gui formed the Ma-Xia school of painting, which was to be of great importance in later centuries. During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the tradition of landscape painting continued, most notably the Wu School, led by Shen Zhou, and the Zhe School.

The Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) is often considered to be a period of stagnation in Chinese painting (see for example “Historia Universal de la Pintura“, published by Espasa Calpe, 1996, volume 8), but it should be noted that for the first time several artists decided to break with the tradition of landscape painting, opting for greater compositional freedom. Towards the end of this period, the influence of European painters began to be noticeable in many Chinese painters, although others, such as Qi Baishi, remained faithful to tradition.

Despite the availability of other media, such as video and performance, painting remains a fundamental part of contemporary art in China, with painters such as Zeng Fanzhi and Yue Minjun enjoying international recognition.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: