Byzantine art

Under domes of gold

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

W. B. Yeats: “Sailing to Byzantium”

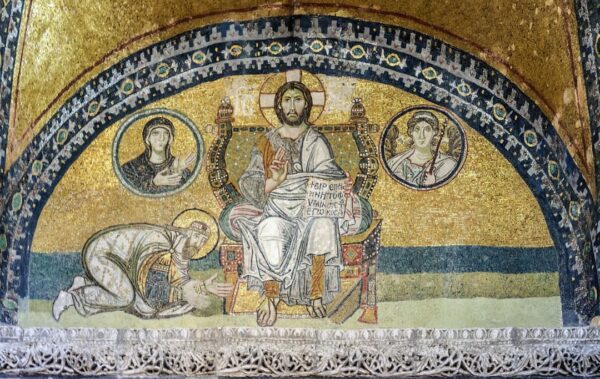

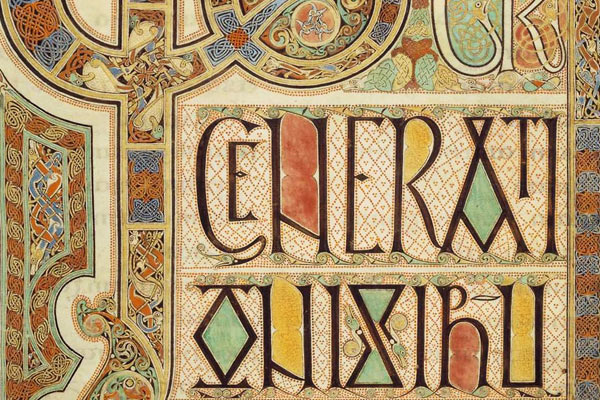

Images: View of the dome of Hagia Sophia. Photograph by Christophe Meneboeuf ·· Archangel, ivory panel from a Byzantine diptych. Constantinople (AD 525-550). British Museum (London). Photograph by Michel Wal ·· Hagia Sophia, Constantinople. Mosaic of the southwest entrance. 10th-11th century.

Byzantium, or the Byzantine Empire, is the name given to the Eastern Roman Empire that survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire at the end of the 5th century, going through periods of expansion and decline until the 15th century. Its capital, Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), founded on the ancient Greek colony of Byzantium, was once the major cultural, religious and economic centre of the Western world, and the Byzantine Empire is generally considered to have been born with the founding of the city in 330 AD, and died with the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, which is traditionally regarded as the end of the Middle Ages.

The main influence of Byzantine art is, not surprisingly, the Roman art of the Eastern Roman Empire, heavily Christianised at the time. The mosaics, so widely used by the Romans, continue in the Byzantine world, now depicting emperors and characters from Christian iconography. In architecture, the shape of the floor plans of Christian churches, the Latin cross, led to the appearance of square-shaped spaces. In order to cover these spaces with domes, one of the great contributions of Roman architecture, solutions such as pendentives were developed, which were essential in the great basilicas of the Byzantine world, such as Hagia Sophia, one of the most important buildings in the world and a symbol of Byzantine art.

The so-called first golden age of Byzantine art, which began in the time of Justinian I, ended with one of the crucial events in the evolution of Byzantine art: the iconoclastic crises in the 8th and 9th centuries, in which numerous Byzantine works were destroyed. This was followed by a second golden age, which ended with the destruction of Constantinople by the Crusaders (1204), an event that plunged Byzantium into “a slow death that dragged on for almost two hundred and fifty years” (Miguel Cortés Arrese: “Byzantine Art”, 1989).

However, this slow political and social decline did not prevent the emergence of a third golden age, which persisted until the aforementioned Fall of Constantinople. It was in this late period that the iconographic types that would influence all later European religious painting were established, particularly the depictions of the Virgin and Child, such as Hodighitria and the Kyriotissa.

In this respect, it is important to note that Byzantine art influenced both Western and Islamic art. It has already been noted in the chapter on Islamic art that “at the beginning of conquests, Muslims admired the art of the conquered Christian world, noing the brilliance of church decoration as a superior technique (…) The Byzantine mosaicists were brought, in order to decorate the mosque of Damascus and probably that of Medina.” (Hee Sook Lee-Niiniona, “Islamic calligraphy & Muslim identity”, 2018). And in European painting, the influence that Byzantine iconographic types had on the early Italian painters, such as Cimabue, Duccio and Giotto, is evident.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: