Baroque Art

Breaking with the order

“I would define the baroque as that style that deliberately exhausts (or tries to exhaust) its own possibilities, and that borders on self-caricature. The baroque is the final stage in all art, when art flaunts and squanders its resources.”

Jorge Luis Borges

Baroque masterpieces: “The Night Watch” by Rembrandt, 1642. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam ·· Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi. Design by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1651. Photograph: Paul Hermans

Origin of Baroque Art

By the mid-16th century, the first signs of weakening in the prevailing Renaissance style began to be evident in Italy, which had been the cradle of the movement. Michelangelo, one of the great figures of the Renaissance, had already shown an inventive freedom that challenged the Renaissance order in works such as his staircase for the Laurentian Library in Florence. Almost at the same time, Titian painted “The Death of Saint Peter Martyr” in Venice, a work of hitherto unknown drama and violence, known today only through copies, as the original was destroyed in the 19th century. Shortly afterwards, Mannerist artists such as Andrea del Sarto and Federico Barocci, and the Venetian painters of the Cinquecento, such as Titian and Tintoretto, continued to show their admiration for the Renaissance masters, but left behind any interest in classical order and moved closer to a style that displayed an exaggeration and theatricality which were absent in the Renaissance.

All this paved the way for the advent of the first great figure of Baroque painting: Caravaggio, whose dramatic, tenebrist style inaugurated a new era in painting. In the words of André Berne-Joffroy, “what begins in the work of Caravaggio is, quite simply, modern painting”. Caravaggio’s work, along with that of the Mannerists, was admired by Peter Paul Rubens, who, on his return to Antwerp, inaugurated the Baroque style in Northern Europe and, in turn, inspired masters such as Velázquez.

Early Baroque: Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola and Giacomo Della Porta: Chiesa del Gesù, Rome. Photo by Nicholas Gemini ·· Caravaggio: “The Cardsharps”, c.1594. Kimbell Art Museum

At the same time, Italian architecture also began to see “cracks” in the Renaissance order (Leonardo Benevolo, in his “Introduction to Architecture”, devotes an excellent chapter to this phenomenon, under the title “The Crisis of Classicism”). Between 1568 and 1580, the architects Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola and Giacomo Della Porta completed the Church of the Gesù in Rome, a building that defied the concept of a basilica with side naves, opting for a large single nave, ostentatiously decorated with polychrome marble and gilded finishes. In the following century, Bernini (who also brought the Baroque style to sculpture) and Borromini completely abandoned the Renaissance order to inaugurate a freer style, more inclined to optical effects and perspective. The Baroque, in architecture, “is spatial liberation, it is mental liberation from the rules of the treatises, from conventions, from elementary geometry and from everything static” (Bruno Zevi: “Saper vedere l’architettura”, 1948).

Although this essay, in line with the website that hosts it, focuses on the visual arts, we cannot fail to highlight the importance of Baroque music, in which, thanks to composers such as Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Friedrich Händel, musical forms such as the opera and the sonata were born.

All this was largely the consequence of a deeper social phenomenon, related to a profound social crisis that had led to a loss of confidence in Renaissance humanism. During the 16th century, the Roman Church lost much of Northern Europe to the Protestant Reformation, while the Ottoman Empire threatened Western Europe, even ruling Hungary for more than 150 years. The social crisis was followed by an economic crisis that contrasted with the splendour of the century that followed the conquest of America. In this context, the Baroque -dramatic, personal, impulsive and, above all, free- appeared as a reaction to the idealism of the Renaissance.

Diego Velázquez: “Las Meninas”, 1656. Madrid, Museo del Prado ·· Nicolas Poussin: “Et in Arcadia ego”, 1628. Óleo sobre lienzo. Paris, Louvre

The Baroque by country

Italy: the main figures who gave rise to the Italian Baroque (Barocci, Caravaggio, Vignola) have already been mentioned at the beginning of this page. Caravaggio’s enormous influence led to the emergence of a group of followers (called the Caravaggisti) with Artemisia Gentileschi among them. In contrast to the chiaroscuro and the sometimes violent subjects of the Caravaggisti, a more classicist style emerged, led by the figures of Annibale Carracci and Guercino. The great genius of Baroque sculpture, the Michelangelo of his time, was Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who was also an important figure in architecture, a field in which Francesco Borromini excelled.

Flanders: as already mentioned, the Baroque arrived in Flanders with Peter Paul Rubens, an enormously prolific painter whose popularity inspired other painters, such as Velázquez. Jacob Jordaens and Anton van Dyck are somewhat opposing figures. While Jordaens never left Flanders, van Dyck trained in Italy and spent much of his career in England.

Netherlands: the so-called “Dutch Golden Age” is led by the colossal figure of Rembrandt, one of the greatest figures of Baroque painting. The work of Frans Hals, an outstanding portraitist, influenced modern painters such as Édouard Manet. In the Netherlands, landscape painting was an important genre, as shown in the work of painters such as Hobbema and the van Ruysdael brothers. Within the Delft School, the technical perfection of Vermeer‘s work is outstanding.

Spain: Diego Velázquez, the great star of the mature Baroque together with Rembrandt, is the leading painter of the Spanish Golden Age. Other important names in Spanish painting are Francisco de Zurbarán, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo and José de Ribera. In sculpture, Gregorio Fernández created important works of a religious nature, while architecture was led by the Churriguera family. The Spanish Baroque had a great influence on the Baroque painters working in America, like Cristóbal de Villalpando.

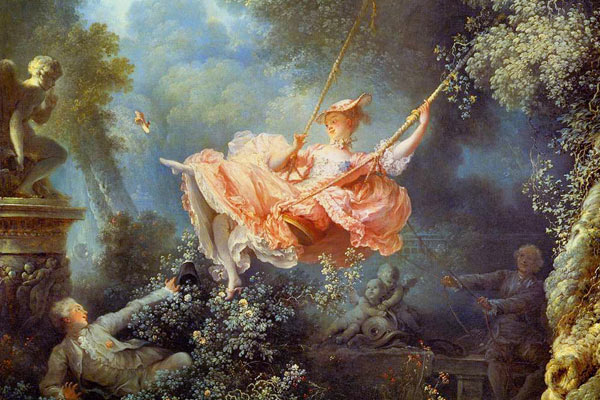

France: French painting was led by the classicism of Nicolas Poussin, who influenced much of later French painting. However, there were also followers of Caravaggio’s tenebrism, such as Georges de La Tour. In architecture, the most outstanding project was the Palace of Versailles, initiated by Louis Le Vau. Many of the most important sculptures of the period were linked to architectural projects, as in the case of François Girardon and his sculptures for the aforementioned Palace of Versailles.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: