Del Arts and Crafts al Art Nouveau

El artesano artista

Con la arrogancia de la juventud, me propuse nada menos que transformar el mundo con la Belleza. Si he tenido éxito de alguna manera, aunque sólo sea en un pequeño rincón del mundo, entre los hombres y mujeres que amo, entonces me consideraré bendecido, y bendecido, y bendecido, y mi trabajo continuará

William Morris

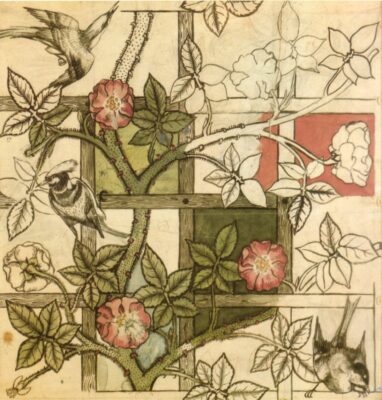

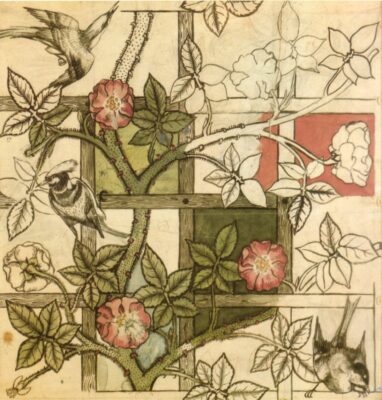

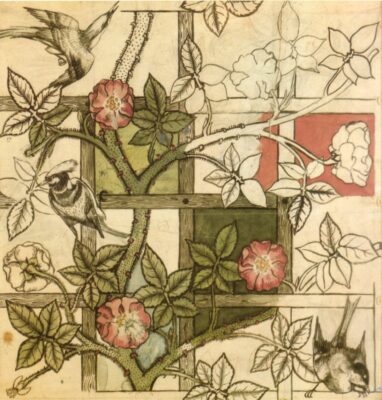

William Morris – Trellis Wallpaper – 1862

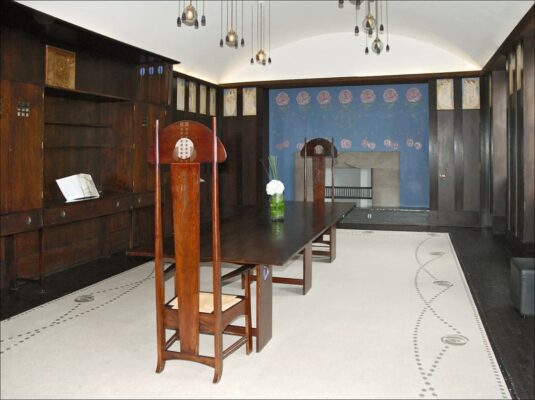

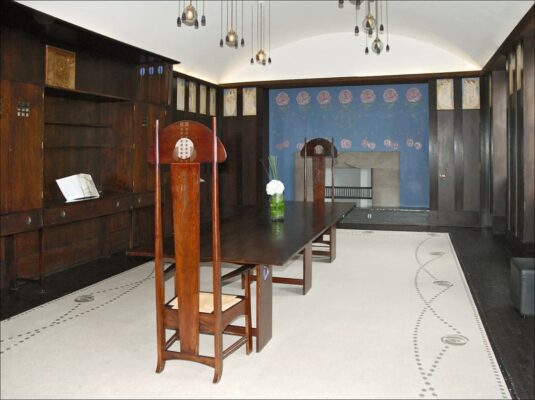

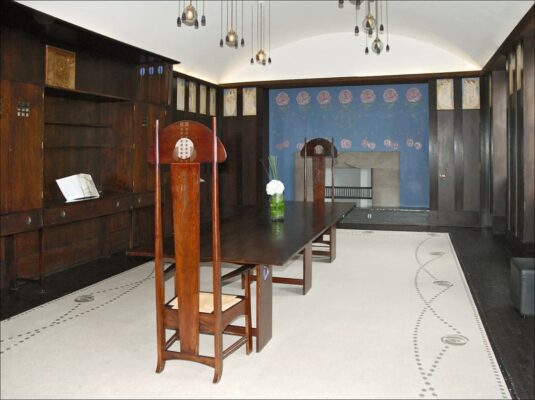

Charles Rennie Mackintosh – dining room – 1901 – photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbera

William Morris: diseño para papel pintado Trellis, 1862 ·· Charles Rennie Mackintosh: comedor para la “Casa para un amante del arte”, 1901. Fotografía de Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, licencia C.C. 2.0.

La secular y algo elitista separación entre Bellas Artes y Artes Decorativas, presente en el arte europeo desde el Renacimiento, comenzó al fin a ponerse en tela de juicio en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. En 1859, William Morris (1834- 1896), buen conocedor de las teorías estéticas de John Ruskin (1819-1900), encarga al arquitecto Philip Webb (1831-1915) la construcción de la Red House, un edificio de estilo neogótico donde dos años más tarde funda la Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., un taller de artistas que buscaban recuperar los métodos artesanales del periodo gótico. El taller, conocido a veces como “the Firm” produjo una gran cantidad de obras, incluyendo murales, vidrieras, tallas, tapices y mobiliario. Morris, cuyo compromiso social estaba claro incluso antes de que entrase a formar parte de la Liga Socialista en 1884, abogaba por un arte accesible para todos, dentro y fuera de sus casas, una belleza que pudiera ser apreciada durante la vida cotidiana. “No quiero el arte para unos pocos, como tampoco quiero la educación para unos pocos o la libertad para unos pocos”, escribió en 1877.

La exposición de las obras de Morris y su taller en la Exposición Internacional de Londres de 1862 atrajo la atención de público y crítica, y podría considerarse como el punto de partida del movimiento Arts and Crafts, que -tras una serie de esfuerzos individuales, destacando el del arquitecto y diseñador Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851-1942) – florecería definitivamente con la formación, en 1887, de la Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, y con la formación de la llamada Escuela de Glasgow. Dentro de esta última resulta fundamental la figura de Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928), que desde muy joven rompió las fronteras entre artista y artesano, ejerciendo como pintor, arquitecto, y diseñador de mobiliario. También debe destacarse a las conocidas como Glasgow Girls, un grupo de mujeres que estudiaron en la Glasgow School of Arts durante un periodo aperturista de la misma, y entre las que destacaron las hermanas Margaret (1864-1933) y Frances MacDonald (1873-1921).

Con la Escuela de Glasgow puede considerarse cumplido el anhelo de Morris de eliminar la separación entre Bellas Artes y Artes Decorativas. Surge así el “Modern Style” británico, que incorpora el gusto por la artesanía del Arts and Crafts junto con la pintura de figuras como Bessie MacNicol (1869-1904). La exposición de las obras de los artistas del Modern Style tendría una gran influencia en los artistas de la Secesión Vienesa, de la que se hablará posteriormente.

Victor Horta – Hotel Tassel staircase – 1893

Hector Guimard – Porte Dauphine – 1901-1903

Victor Horta: Escalera del Hôtel Tassel, 1893 ·· Hector Guimard: Entrada de la estación de metro Porte Dauphine en París, 1900-1903.

El Art Nouveau en Francia y Bélgica

En 1892, un joven arquitecto llamado Victor Horta (1861-1947), proyecta en Bruselas el Hôtel Tassel, completado al año siguiente, en el que el arquitecto rompía con la tipología clásica de edificio de viviendas empleada en Bélgica y Francia hasta entonces. En el Hôtel Tassel, como en otras edificaciones posteriores de Horta (Hôtel Van Eetvelde o la desaparecida Maison du Peuple) el espacio central del edificio es una luminosa zona común, que alumbra un interior en el que la decoración de formas sinuosas es omnipresente. En las obras de Horta, elementos hasta entonces “pasados por alto”, como barandillas y pomos de puertas, se tratan como obras de arte al servicio del habitante. En 1895, el marchante Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) abre en París la Maison de l’Art Nouveau, una galería en la que el término “ecléctico” cobraba una nueva dimensión. En ella, pinturas de Seurat y Toulouse-Lautrec se exponían junto con joyería y vidrieras del americano Louis Comfort Tiffany, de quien se hablará posteriormente. Se podría decir que, al igual que la Exposición Internacional de Londres de 1862 significó la aceptación del Arts & Crafts en Reino Unido, la Exposición Internacional de París de 1900 supuso el gran triunfo del Art Nouveau en Francia y Bélgica. El nouveau style se hace norma, y el París de la Belle Époque se transforma en un museo al aire libre. Hector Guimard (1867-1942) convierte kioskos y entradas de metro en obras de arte. Los posters y decoraciones de Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939) adornan comercios y galerías. Más allá de París, se debe destacar la llamada École de Nancy y, ya fuera de Francia y Bélgica, pero con claras influencias del nouveau style, el Nieuwe Kunst holandés.

Louis Comfort Tiffany – Angel of the Resurrection – 1904

Antoni Gaudi – Casa Batllo – 1904 1906

Louis Comfort Tiffany: Ángel de la Resurrección. Vidriera, 1904. Indianapolis Museum of Art ·· Antoni Gaudí: Casa Batlló, Barcelona. 1904-1906

Art Nouveau en Estados Unidos.

La gran figura del Art Nouveau en Estados Unidos fue Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933). Nacido en el seno de una acomodada familia de joyeros, Tiffany pudo estudiar arte con maestros tan distinguidos como George Inness en Nueva York y León Bailly en París. Influenciado por el Arts and Crafts de Morris, estableció su propio estudio de vidrieras en 1885, que iría ampliando con los años.»Lo que comenzó como interpretaciones formales de la naturaleza se convirtió en un amor por el naturalismo exuberante, y a medida que su carrera artística avanzaba, se preocupó cada vez más por las representaciones ilusionistas de paisajes y flores. El suyo no era un enfoque intelectual del arte; más bien era un enfoque sensorial, que proporcionaba festines de color, luz y textura» (Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen: “Louis Comfort Tiffany at the Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 1998). Además de Tiffany, en Estados Unidos debe mencionarse la figura del diseñador John La Farge (1835-1910) y del arquitecto Louis Sullivan (1856-1924).

Gaudí y el modernismo catalán

La fascinante figura de Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926) domina todo el Modernisme Catalá, que se desarrolló a la par que el Art Nouveau franco-belga, y que se manifestó sobre todo en la arquitectura. Hombre de profundas convicciones religiosas, para Gaudí la naturaleza (la creación divina) es su maestra, y de su observación surgen las formas orgánicas presentes en sus obras, desde proyectos residenciales (Casa Batlló, Casa Milà), urbanos (Parque Güell) o religiosos (Templo de la Sagrada Familia). Tras Gaudí, podemos destacar las figuras del arquitecto Lluís Domènech i Montaner (1849-1923) y del pintor y diseñador Ramón Casas (1866-1932)

Modernismo nórdico: el Jūgendstil En el norte de Europa (Alemania, Escandinavia y el Báltico), el Art Nouveau se conoce habitualmente como Jūgendstil (“Estilo Joven”), nombre tomado de una influyente revista de arte fundada en 1896 por el crítico Georg Hirth (1841-1916), quien también dio nombre a la llamada Secesión de Múnich, grupo de artistas que influiría notablemente en las posteriores Secesión de Berlin y la más famosa Secesión de Viena. En Escandinavia destacaron los arquitectos y diseñadores finlandeses Lars Sonck (1870-1956) Eliel Saarinen (1873-1950). Riga, capital de Letonia, fue un importante centro modernista, destacando la obra del arquitecto Konstantīns Pēkšēns (1859-1928)

Josef Hoffmann – Palais Stoclet – photo by PtrQs

Gustav Klimt – The Kiss – 1907

Josef Hoffmann: Palacio Stoclet, Bruselas, 1905-1911. Fotografía de PtrQs, licencia C.C. 4.0 ·· Gustav Klimt: “El Beso”, 1907-08. Viena, Belvedere.

“A cada tiempo su arte, a cada arte su libertad”: la Secesión Vienesa

Uno de los grupos modernistas más polifacéticos e importantes fue la llamada Secesión Vienesa o Secesión de Viena, fundada en 1897. Al contrario que las Secesiones alemanas, que se encuadraron claramente dentro del Jūgendstil de inspiración Nouveau, la de Viena “desarrolló su propio ‘estilo de secesión’, centrado en la simetría y la repetición más que en las formas naturales. La forma dominante fue el cuadrado, y los motivos recurrentes la cuadrícula y el damero” (Roberto Rosenman: «Vienna Secession, 1898-1905)». Este “gusto por el orden” es apreciable en las dos grandes obras arquitectónicas de la Secesión de Viena: el Pabellón de la Secesión, de Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867-1908) y, sobre todo, el Palacio Stoclet, de Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956)

Pero, al contrario que en otros centros modernistas, la figura más destacada de la Secesión de Viena no fue un arquitecto ni un diseñador, sino un pintor. Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), artista de formación académica, desarrolló un estilo personal, de inspiración claramente simbolista que alcanzó su apogeo en la primera década del siglo XX, en su llamado “Periodo Dorado”, con obras como el “Retrato de Adele Bloch-Bauer I” y “El Beso”, ambas pintadas en 1907-1908. El estilo de Klimt influiría de forma decisiva en Egon Schiele (1890-1918), quien al final de su corta vida había evolucionado ya hacia la pintura expresionista.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

From Arts and Crafts to Art Nouveau

The artisan-artist

With the arrogance of youth, I determined to do no less than to transform the world with Beauty. If I have succeeded in some small way, if only in one small corner of the world, amongst the men and women I love, then I shall count myself blessed, and blessed, and blessed, and the work goes on

William Morris

William Morris – Trellis Wallpaper – 1862

Charles Rennie Mackintosh – dining room – 1901 – photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbera

William Morris: design for Trellis wallpaper, 1862 ·· Charles Rennie Mackintosh: dining room for the «House for an Art Lover», 1901

The secular and somewhat elitist separation between Fine Arts and Decorative Arts, present in European art since the Renaissance, finally began to be questioned in the second half of the 19th century. In 1859, William Morris (1834- 1896), well acquainted with the aesthetic theories of John Ruskin (1819-1900), commissioned the architect Philip Webb (1831-1915) to build the Red House, a neo-Gothic style building where two years later Morris founded the Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co, a workshop of artists who sought to recover the craft methods of the Gothic period. The workshop, sometimes known as «the Firm» produced a large body of work, including murals, stained glass, carvings, tapestries and furniture. Morris, whose social commitment was clear even before he joined the Socialist League in 1884, advocated art accessible to all, inside and outside their homes, beauty that could be appreciated during everyday life. «I do not want art for a few, any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few,» he wrote in 1877.

The exhibition of the works of Morris and his workshop at the London International Exhibition of 1862 attracted the attention of the public and critics, and could be considered the starting point of the Arts and Crafts movement, which -after a series of individual efforts, most notably that of the architect and designer Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851-1942)- would flourish definitively with the formation, in 1887, of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, and with the formation of the so-called Glasgow School. Within the latter, the most important figure was Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928), who from a very young age broke the boundaries between artist and craftsman, working as a painter, architect and furniture designer. Also worthy of note are the Glasgow Girls, a group of women who studied at the Glasgow School of Arts, among them the sisters Margaret (1864-1933) and Frances MacDonald (1873-1921).

With the Glasgow School, Morris’s desire to eliminate the separation between Fine Arts and Decorative Arts can be considered fulfilled. Thus arose the British «Modern Style», which incorporated the taste for craftsmanship of the Arts and Crafts movement along with the painting of figures such as Bessie MacNicol (1869-1904). The exhibition of the works of the artists of the Modern Style would have a great influence on the artists of the Viennese Secession, which will be discussed later.

Victor Horta – Hotel Tassel staircase – 1893

Hector Guimard – Porte Dauphine – 1901-1903

Victor Horta: Staircase of the Hôtel Tassel, 1893 ·· Hector Guimard: Entrance to the Porte Dauphine metro station in Paris, 1900-1903.

Art Nouveau in France and Belgium

In 1892, a young architect named Victor Horta (1861-1947) designed in Brussels the Hôtel Tassel, completed the following year, in which the architect broke with the classical typology of residential buildings used in Belgium and France until then. In the Hôtel Tassel, as in other later buildings by Horta (Hôtel Van Eetvelde or the now destroyed Maison du Peuple), the central space of the building is a luminous common area, which illuminates an interior in which the decoration of sinuous lines is omnipresent. In Horta’s works, hitherto «overlooked» elements such as railings and doorknobs are treated as works of art in the service of the inhabitant.

In 1895, the art dealer Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) opened the Maison de l’Art Nouveau in Paris, a gallery where the term «eclectic» took on a new dimension. In it, paintings by Seurat and Toulouse-Lautrec were exhibited alongside jewelry and stained glass by the American Louis Comfort Tiffany, of whom we will speak later. It could be said that, just as the London International Exhibition of 1862 signified the acceptance of Arts & Crafts in the United Kingdom, the Paris International Exhibition of 1900 was the great triumph of Art Nouveau in France and Belgium. The nouveau style became the norm, and the Paris of the Belle Époque was transformed into an open-air museum. Hector Guimard (1867-1942) turns kiosks and subway entrances into works of art. Posters and decorations by Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939) adorned stores and galleries. Beyond Paris, we should mention the so-called École de Nancy and -outside France and Belgium, but with clear influences of the nouveau style– the Dutch Nieuwe Kunst.

Louis Comfort Tiffany – Angel of the Resurrection – 1904

Antoni Gaudi – Casa Batllo – 1904 1906

Louis Comfort Tiffany: Angel of the Resurrection. Stained glass, 1904. Indianapolis Museum of Art ·· Antoni Gaudí: Casa Batlló, Barcelona. 1904-1906

Art Nouveau in the United States.

The great figure of Art Nouveau in the United States was Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933). Born into a wealthy family of jewelers, Tiffany was able to study art with such distinguished masters as George Inness in New York and Leon Bailly in Paris. Influenced by Morris’s Arts and Crafts, he established his own stained glass studio in 1885, which he would expand over the years. “What began as formal interpretations of nature grew into a love of lush naturalism, and as his artistic career progressed, he became increasingly preoccupied by illusionistic depictions of landscapes and flowers. His was not an intellectual approach to art; rather it was a sensory one, providing feasts of color, light, and texture” (Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen: “Louis Comfort Tiffany at the Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 1998). In addition to Tiffany, the two main figures of American Art Nouveau were the designer John La Farge (1835-1910) and the architect Louis Sullivan (1856-1924).

Gaudí and Catalan Modernisme

The fascinating figure of Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926) dominated all of Catalan Modernisme, which developed alongside Franco-Belgian Art Nouveau, and which manifested itself above all in architecture. A man of deep religious convictions, for Gaudí nature (divine creation) was his only teacher, and from its observation arise the organic forms present in his works, from residential (Casa Batlló, Casa Milà), urban (Park Güell) or religious projects (Temple of the Sagrada Familia). After Gaudí, we can highlight the figures of the architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner (1849-1923) and the painter and designer Ramón Casas (1866-1932).

Nordic modernism: the Jūgendstil

In northern Europe (Germany, Scandinavia and the Baltic Region), Art Nouveau is commonly known as Jūgendstil («Young Style»), a name taken from an influential art magazine founded in 1896 by the critic Georg Hirth (1841-1916), who was also an important figure in the so-called Munich Secession, a group of artists that would notably influence the later Berlin Secession and the more famous Vienna Secession. In Scandinavia, Art Nouveau is represented by the works of the Finnish architects and designers Lars Sonck (1870-1956) and Eliel Saarinen (1873-1950). Riga, capital of Latvia, was an important modernist center, having the architect Konstantīns Pēkšēns (1859-1928) as its most important figure.

Josef Hoffmann – Palais Stoclet – photo by PtrQs

Gustav Klimt – The Kiss – 1907

Josef Hoffmann: Stoclet Palace, Brussels, 1905-1911. Photograph by PtrQs, C.C. license 4.0 ·· Gustav Klimt: «The Kiss,» 1907-08. Vienna, Belvedere.

«To every age its art, to every art its freedom»: the Vienna Secession

One of the most multifaceted and important modernist groups was the so-called Viennese Secession or Vienna Secession, founded in 1897. Unlike the German Secessions, which were clearly framed within the Nouveau-inspired Jūgendstil, the Vienna Secession “developed its own unique ‘Secession style’ centred around symmetry and repetition rather than natural forms. The dominant form was the square and the recurring motifs were the grid and checkerboard” (Roberto Rosenman: “Vienna Secession”, 1898-1905). This «taste for order» can be seen in the two great architectural works of the Vienna Secession: the Secession Pavilion by Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867-1908) and, above all, the Stoclet Palace by Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956).

But, unlike in other modernist centers, the most prominent figure of the Vienna Secession was neither an architect nor a designer, but a painter. Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), an academically trained artist, developed a personal, clearly symbolist-inspired style that reached its peak in the first decade of the 20th century, in his so-called «Golden Period», with works such as «Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I» and «The Kiss«, both painted in 1907-1908. Klimt’s style would decisively influence Egon Schiele (1890-1918), who by the end of his short life had already evolved towards expressionist painting.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com