American Art styles

Inheritances and identities of a young country

Of course, it is well to go abroad and see the works of the old masters, but Americans must branch out into their own fields as they are doing it. They must strike out for themselves, and only by doing this will we create a great and distinctly American art

Thomas Eakins

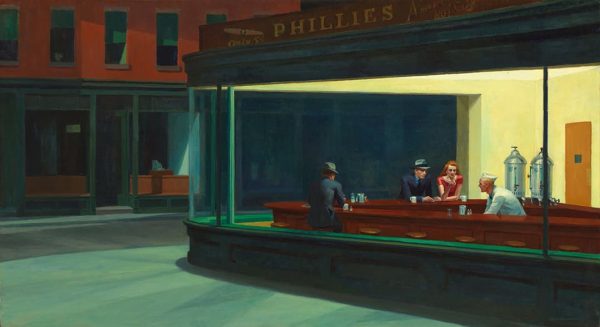

Tonalism: George Inness, “Sunset on the Passaic”, 1891. Oil on canvas, Honolulu Museum of Art ·· American realism: Edward Hopper, “Nighthawks”, 1942. Oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago. © Artists Rights Society, New York.

American art, from the New Hispanic Baroque of Mexico until the outbreak of World War II, generally followed a line of evolution parallel to European art, adopting the styles to the American particularity. For this reason, in this section of Artistic Periods and Styles, a specific chapter for American art has not been created to this point (beyond, of course, those dedicated to Pre-Columbian and Native American art), opting instead to comment on such American particularities within the corresponding chapter. For example, the Hudson River School has been included within the chapter devoted to Romanticism, and the same strategy has been followed to explain the distinctive characteristics of American Neoclassicism and Impressionism, or Latin American Surrealism. Nevertheless, there are certain movements that had no direct equivalent in Europe, which we have included in the present chapter.

Tonalism

Tonalism emerged in the United States in the last quarter of the 19th century, characterized by its melancholic, atmospheric and hazy landscapes. “Tonalist light is memory incarnate, memory filtered, memory infused, while the use of memory, the perfection of memory to render specific qualities of light was considered both a practical skill … and a necessary discipline of the professional artist.” (David Cleveland: A History of American Tonalism 1880-1920). Tonalism, which found in George Innes (1825-1894) and James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) its most famous practitioners, was short-lived, being soon obscured by American Impressionism, but constitutes perhaps the first distinctively American artistic style.

American Realism. Regionalism and the Ashcan School.

In European art, the term “realism” is usually identified with the artistic movement of the mid-19th century, led by Courbet and the painters of the Barbizon School. In the United States, although nineteenth-century realism had such notable representatives as Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) and Winslow Homer (1836-1910, although Homer -who may have been the most important artist of nineteenth-century America- cannot be considered purely realist); Realism in American art had its heyday in the early twentieth century, coinciding with a period of enormous change in American society.

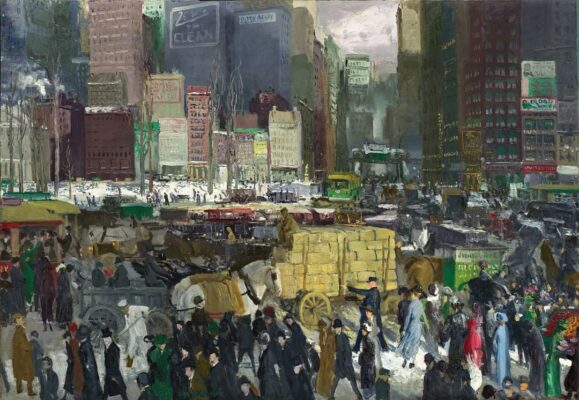

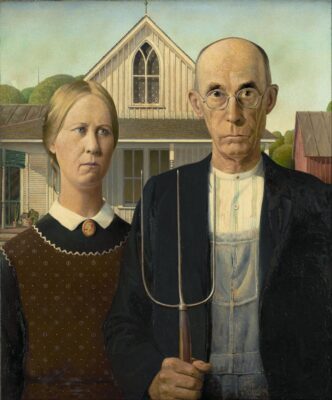

American Realism (Ashcan School): : George Bellows, “New York”, 1911. Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington ·· American Realism (regionalism): Grant Wood, “American Gothic”, 1930. Oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago.

Early twentieth-century New York saw the birth of an artistic group known as “The Eight,” which included Robert Henri (1865-1929), John Sloan (1871-1951), and Everett Shinn (1876-1953), who would give rise to a larger group, the so-called Ashcan School, an unorganized group of painters fascinated by the vibrant, bustling atmosphere of the city. The artists of the Ashcan School “documented an unsettling, transitional time in American culture that was marked by confidence and doubt, excitement and trepidation” (H. Barbara Weinberg: “The Ashcan School,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010).

Related to a greater or lesser extent to the Ashcan School are the two most important American realist painters of the 20th century: George Bellows (1882-1925) and Edward Hopper (1882-1967). George Bellows was undoubtedly the great chronicler of New York life at the beginning of the 20th century, which he depicted on a multitude of levels, both in urban views (“New York“, 1911) and sports scenes (“Dempsey vs. Firpo“, 1924). For his part, Edward Hopper never considered himself part of any school (“The only real influence I have had was myself,” he wrote in 1956), but he is linked to the Ashcan School by his interest in urban life, which Hopper often depicts as solitary and enigmatic, as in his celebrated “Nighthawks” (1942).

In the aftermath of the Great Depression, Regionalism or regionalist realism emerged. While the Ashcan School focused on vibrant urban life, sometimes with an excess of optimism, Regionalism focuses on rural life, more static and sometimes somber. “American Gothic” (1930), the work of Grant Wood (1891-1942) is the best-known painting of this movement, and an icon of American art.

American Realism continued to have notable representatives throughout much of the 20th century, most notably Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) and Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009).

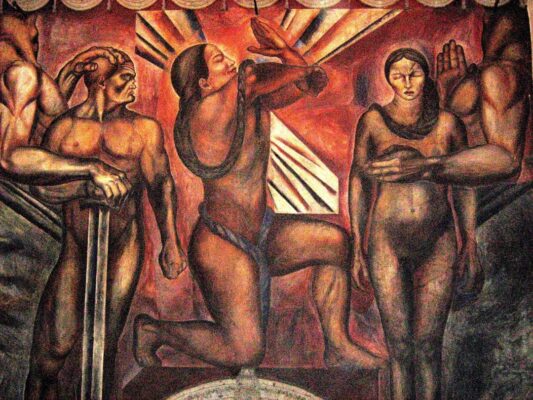

Precisionism: Charles Demuth, “I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold”, 1928. Oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art ·· Mexican muralism: José Clemente Orozco, “Omnisciencia”, 1925. Mural, Historic centre, Ciudad de México..

Precisionism: between cubism and realism

Precisionism is a heterogeneous artistic style, which, starting from a realist background, took elements from Cubism and Futurism, being particularly interested in the urban and industrial landscapes of the 1920s and 1930s America. Its most notable representative was probably Charles Demuth (1883-1925), author of “I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold” (1928), one of the most famous and studied paintings of American art, in which Cubist and Futurist elements are found within a composition that seems to anticipate the Pop Art of the 1960s.

Mexican Muralism

After the Mexican Revolution of 1910, Mexican artists sought to participate in the creation of a national identity. The monumental works of the Mexican muralists clearly expressed nationalist, socialist and, in part, indigenous ideas. In this sense, “the iconography of muralism, by recreating the image of the workers’ and peasants’ revolution, creates a consecrating art that the State used in its process of national legitimization and homogenization” (Claudia Mandel: “Mexican Muralism: public art / identity / collective memory”, 2007).

The three great representatives of muralism were José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949), Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974). Orozco is the author of the frescoes of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, notable for his criticism of justice in an institutional building. Siqueiros -a painter who was imprisoned for his participation in the assassination attempt on Leon Trotsky- painted “The people to the university, the university to the people” at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Rivera’s most famous work is “Man at the Crossroads“, commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller for Rockefeller Plaza, which generated enormous controversy for its defense of socialism in the epicenter of capitalism, which eventually led to its destruction when Rivera refused to “soften” the painting’s message.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: