Beginnings of Abstract Art

The language of pure painting

Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammer, the soul is the strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul

Wassily Kandinsky

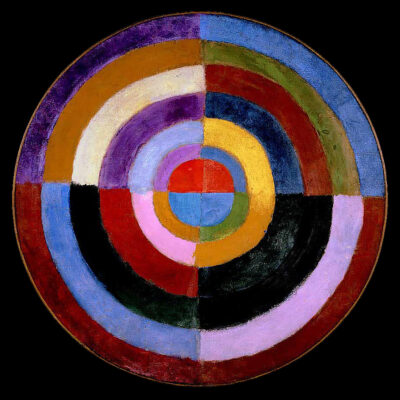

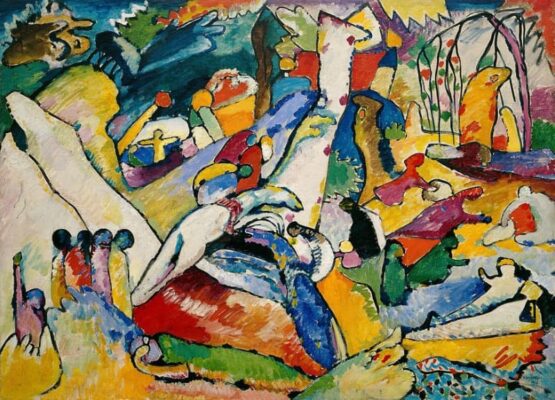

Wassily Kandinsky: “Composition VII”, 1913, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow ·· Robert Delaunay: “Le Premier Disque”, 1912–13. Private collection.

One of the great debates in the study of the history of art is that which attempts to locate the origin of abstract art, and, given the ambiguity of the term “abstraction” (and even of the term “art” itself) it does not seem that it can be resolved for good. Leaving aside the definitions used in fields such as philosophy or mathematics, in the study of art the term “abstraction” or “abstract art” is used to refer to art which, as opposed to “figurative art”, does not have as its object the representation (not even subjective, as the expressionists or the fauves proposed) of observable reality. From this point onwards, various critics and artists have expressed, with varying degrees of clarity, different views on what abstract art means to them. For example, for Piet Mondrian, one of the great figures of geometrical abstraction, abstraction is almost a necessary condition for art: ” Art is higher than reality and has no direct relation to reality. To approach the spiritual in art, one will make as little use as possible of reality, because reality is opposed to the spiritual. We find ourselves in the presence of an abstract art. Art should be above reality, otherwise it would have no value for man“.

It is important to note, however, that when the term “abstraction” is coupled with “art”, thus speaking of “abstract art”, we are implying (at least until the advent of conceptual art) an intention, on the part of the artist, to communicate through abstract form. This is a key point in the search for the origin of abstract art, since, as seen in previous entries, abstract forms have existed in art throughout its history. In fact, what has been called prehistoric abstract art -which Professor Louis-René Nougier (“History of Art”, Salvat Editores, Vol. 1, 1981) distinguishes between “derived” abstract art (Lascaux) and “pure” abstract art (Mezin)- can be found as early as the Palaeolithic period. Similarly, many arabesques and geometries typical of Islamic art, as well as several reliefs on wood from Oceania, lack a figurative message. In the Western tradition, the last paintings of Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1881), such as his “Sunrise with Sea Monsters” (1845); or “Nocturne in Black and Gold” (1874) by James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), as well as several canvases from the “Water Lilies” series by Claude Monet (1840-1926), have been proposed as “abstract” to a greater or lesser extent. Despite the boldness of all these works, in none of them can one be sure of an artist’s desire to detach himself definitively from observable reality.

Background to abstract art: Joseph Mallord William Turner, “Sunrise with Sea Monsters”, 1845 ·· James McNeill Whistler: “Nocturne in Black and Gold” 1874

An exceptional case is the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862-1944), whose interest in spiritualism led her to create, from 1906 onwards, a series of paintings (“Paintings for the Temple“) whose genesis is similar to the automatic writing and drawing that Klint and several friends practised during their séances. It is possible that these mystically themed works (“Primordial Chaos“, “Seven-pointed Star“, etc.) constitute the first attempt to represent a reality other than the observable one, at least in the European tradition. In this respect, “Much of the debate concerning the historical significance [of Klint’s work] has revolved around the question of whether the artist developed an abstract style of painting before the artists who have traditionally been regarded as the initiators of this style (…) However, it seems that the most important thing is not to decide which artist was the first to produce abstract images, (…) but how an artist in Af Klint’s situation (who was relatively marginal, both geographically and personally) was able to develop a new visual style. (…) It is hard to believe that this artist was unaware of the radical novelty of her visual style when she began to paint non-mimetic works around 1905, and that is what makes her artistic trajectory fascinating“. (Marco Pasi, “Hilma af Klint, Western Esotericism and the Problem of Modern Artistic Creativity”, 2014). As fascinating as the figure of Hilma af Klint is, it is not clear that her works were decisive in the genesis of abstract art, as, by the artist’s own choice, they were not exhibited until years after her death, although some authors have suggested that Kandinsky may have seen her paintings in 1908.

Along with Klint’s work, the other “Oopart” of early abstraction is “Caoutchouc,” a painting by Francis Picabia (1879-1953) that most critics date to 1909, earlier than any abstract work by Kandinsky, Delaunay or the other names discussed below. Both the date and the very “abstract” nature of the work have been called into question, with several historians linking the painting to Picabia’s works of around 1913-14, proposing that the apparently abstract form is in fact an unidentified Cubist composition. “Despite the numerous descriptions of ‘Caoutchouc’ as the first abstract picture, the most recent scholarship has acknowledged that certain vestiges of recognizable form betray it as the end of one line of development rather than the beginning of the next” (Robert J. Belton: “Picabia’s ‘Caoutchouc’ and the Threshold of Abstraction”, 1982).

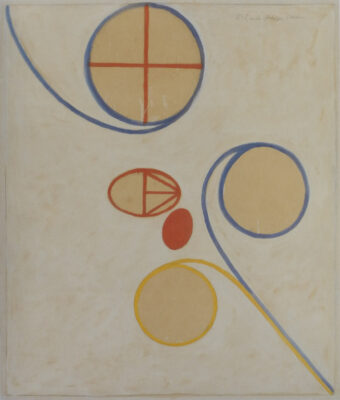

Hilma af Klint: “The seven-pointed star”, 1908 ·· Francis Picabia: “Caoutchouc”, c.1909

The first undisputedly abstract paintings in European art are those of the so-called Lyrical Abstraction, which began around 1910, of which Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) is its most notable representative. Kandinsky, who had painted his first works in a realist style typical of Russian painters of the time, had an “artistic epiphany” when he saw Claude Monet’s “Haystacks”. “ And suddenly for the first time a saw a picture. The catalogue told me it was a haystack of Claude Monet; I couldn’t tell it from looking. (…) What was quite plain to me, however, was that the palette had a strength that I have never before suspected, far beyond anything that I had ever dreamt“. The other major influence on Kandinsky’s evolution towards abstraction was the abstract art par excellence: music. “The affinity between music and painting for Kandinsky ‘is the starting point of the path by which painting, with the help of its own means, will develop into art in the abstract sense. Paradoxically, the most abstract of the arts is for them the one that is closest to reality” (María Santos García Felguera: “Las vanguardias históricas”, 1993).

In 1910 Kandinsky painted his “First Abstract Watercolour” and between 1910 and 1913 he created seven large works, which he called simply “Compositions“, which in themselves illustrate the evolution of Kandinsky’s style from Expressionism to pure abstraction. The first three have unfortunately been lost, although black-and-white photographs or sketches of them have survived.

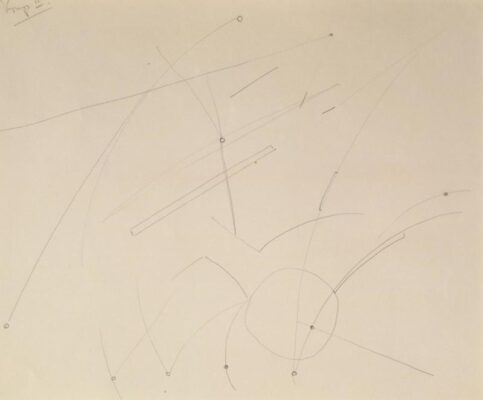

Kandinsky’s “Compositions”: “Composition I”, 1910. Lost, black and white photograph ·· “Study for ‘Composition II’”, 1910. Oil on canvas, 97.5 x 131.1 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York ·· “Schematic Study for ‘Composition III’”, 1910. Drawing, 24.8 x 29.7 cm. Pompidou, Paris ·· “Composition IV”, 1911. Oil on canvas, 159.5 x 250.5 cm. Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen ·· “Composition V”, 1911. Oil on canvas, 190 x 275 cm. Private collection, New York ·· “Composition VI”, 1913. Oil on canvas, 195 x 300 cm. St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum ·· “Composition VII”, “1913. Oil on canvas, 200.6 × 302.2 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

In Paris, between 1911 and 1912, several artists began to experiment with lyrical abstraction. The Czech František Kupka (1871-1957) exhibited his abstractions -strongly Futurist in inspiration- at the Salon of 1912, while Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979) and Robert Delaunay (1885-1941) developed Orphism, an abstract style strongly influenced by Cubism and Fauvism. Also, between 1911 and 1914 Piet Mondrian, who would become one of the leading figures of geometric abstraction years later, worked in Paris, although at that time he had not yet incorporated abstraction into his pictorial language.

Another focus of experimentation with abstract art was in Russia. Rayonism, of which Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962) is its most prominent representative, displays an even more evident Futurist influence than that of Kupka’s works. But the great figure of Russian abstraction, Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935), would not reach artistic maturity until 1915, with the creation of Suprematism, which Malevich described as art based on “the supremacy of pure feeling in the pictorial arts. From the Suprematist point of view, the appearances of natural objects are in themselves meaningless; the essential thing is feeling” (Kazimir Malevich, 1927). Malevich presented his works in the so-called Last Futurist Exhibition: 0,10, including his now famous (and still controversial) “Black Square“. “The square is not a subconscious form. It is the creation of intuitive reason”, Malevich wrote in 1916. “The face of the new art. The square is a living, regal infant. The first step of pure creation in art”. In addition to Malevich, the versatile El Lisitsky (1890-1941) also contributed to the later development of Suprematist painting.

Kazimir Malévich: “Black Square”, 1915. Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow ·· Vladímir Tatlin: “Monument to the Third International” (Tatlin´s Tower), 1919.

Along with Malevich, the great figure of Russian art of the period was Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953), painter, designer and architect, the leading representative of Russian Constructivism, along with the sculptor and painter Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956). The “Monument to the Third International” (1919), which could be considered Tatlin’s artistic manifesto, was a project of pharaonic dimensions, never built, a “total work of art, in which the differences between architecture, sculpture and painting disappear, dissolving as they are integrated into the extraordinary utopia of intelligent totality” (Javier Arnaldo: “Las Vanguardias Históricas”, Volume I, 1989). The project was criticised by many contemporaries, and Malevich himself accused Tatlin of “not transcending the confines of Cubism”.

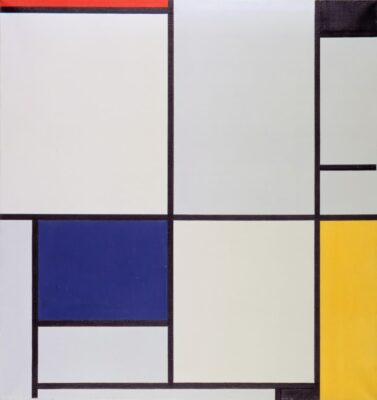

Besides Russia, the second focus of Geometric Abstraction was the Netherlands. Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), who had become acquainted with the work of the Cubists in Paris, developed an abstract style dominated by horizontal and vertical lines on his return to Holland during the First World War. Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931) shared this interest, and the two co-founded the magazine De Stijl, which later gave its name to the movement also known as Neoplasticism or Dutch Constructivism. While for Kandinsky and the practitioners of Lyrical Abstraction one source of inspiration was the most abstract of the arts -music- the Neo-Plasticists also drew inspiration from the most abstract of the sciences: mathematics. “That is why De Stijl quotes this phrase from the Book of Proverbs: ‘Omnia in mesura et numero et pondere disposuisti’. It is in this conception of harmony that the principles of mathematics and music meet again” (L. C. Jaffé: “Geometric Abstraction”, 1918).

Piet Mondrian: “Tableau I (Schilderij I)”, 1921. Kunstmuseum Den Haag ·· Gerrit Rietveld: Rietveld Schröder Hoouse, Utrecht, 1924. Photo by Basvb, license C.C. 3.0

After the end of the First World War, the De Stijl group became more heterogeneous, partly thanks to Van Doesburg’s collaboration with the hyperactive Bauhaus, which opened the door for the movement’s ideas to be reflected in other fields, such as architecture, but also caused some members, including Mondrian himself, to lose interest and leave the movement. Between 1924 and the late 1930s, the ideas of Van Doesburg and the Bauhaus gave rise to a series of fabulous examples of architecture -such as the Rietveld Schröder House by the architect Gerrit Rietveld (1888-1964)- and design, while Mondrian’s career seemed to stagnate. Due to the growing threat of Nazism, in 1940 Mondrian was forced to leave Europe and settle in New York. In America, his career was reinvigorated, and the austerity of the lines began to give way to a more emotional quality, inspired by jazz music and the vibrant urban atmosphere of New York. “The Modern City! Precise, rectangular, squared, whether seen from above, below, or on the side; bright lights and sterilized life; Broadway, whites and blacks; and boogie-woogie; the underground music of the at once resigned and rebellious. Mondrian has left his white paradise and entered the world,” wrote Robert Motherwell about Mondrian’s “Boogie-Woogies”. The Dutch artist died of pneumonia in New York in 1944, leaving his last pictorial testament, his “Victory Boogie Woogie” (1944, Kunstmuseum The Hague), unfinished.

G. Fernández · theartwolf.com

Follow us on: