Hudson River School · A taste for the landscape

“Everything in the Nature contains all the powers of the Nature. Everything is done of hidden stuff”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

by G. Fernández – theartwolf.com

Take a look at this painting: we see two men at the top of the rocks, contemplating a fantastic fluvial valley, studded with rocks, shrubs and water jumps. A majestic tree embraces the scene, giving shelter to the men admiring the marvelous landscape. Two clearly symbolic elements – the waterfall and the eagle- emphasize an imaginary vertical line, dividing and organizing the composition. Everything is peaceful; everything is perfect within the grandiloquence of the Nature. The painting we are talking about is, of course, Asher Brown Durand’s “Kindred spirits”, an emblematic and paradigmatic work from the Hudson River School.

Within that fascinating artistic period that the American 19th century is, no tendency or movement is more interesting and suggestive than the Hudson River School. The painters of this school gave a radical turn to the developing of landscape painting, making the landscape no longer a simple background for a religious, historical or mythological composition and turning it into the authentic reason and protagonist of the picture. But there is more, much more to speak about. In this small essay we are going to try to discover some less evident aspects of this sensational artistic period.

There is much to say about the artists who may have influenced this movement. Some of them are quite evident, such as the late Baroque landscape painters -Meindert Hobbema, Claude Lorrain- in works by Thomas Cole or Asher Brown Durand. More complex, but maybe even more important, is the influence of the greatest American writers of that time, like Ralph Waldo Emerson or Henry David Thoreau. We will study this complex influence in later chapters. Also, we must mention earlier pioneers of the American landscape Art, like George Catlin or Thomas Doughty.

About the influence that this movement had in the immediately later American Art -symbolism, luminism and American impressionism- there is a lot to study. It has been said quite often -and it is difficult not to fall in the temptation of saying it again- that the influence that the painters of the Hudson River School had on American impressionism is similar to what the Barbizon School had on French impressionism. This is not so simple, at least in my opinion. First of all, the so called American impressionism is a much more “heterodox” movement -and generally less studied- than French impressionism: whereas many American artists simply adopted the ideas and techniques of his European contemporaries, some -such as Winslow Homer- developed a very personal and original style, between Realism and Impressionism. In addition, American landscape painting entails very complex political and even spiritual connotations that difference it from French impressionism. In any case, the influence of the Hudson River School in the works of Albert Pinkham Ryder, Ralph Blakelock or Winslow Homer is undeniable.

THE PROTAGONISTS

THOMAS COLE (1801-1858) is known as the founder of the Hudson River School. Born in Britain, his family emigrated to America when he was only 17 years old, so we can consider him a totally American painter. Cole discovered the beauty of the Hudson River in 1825, after emigrating to New York, and began to create his first outdoors sketches. Here he painted some of his more famous works, like “The falls of Kaaterskill” (Warner Collection). His love for the American landscape was so strong that, after travelling to Europe- he found the landscape of the Old Continent cold and desolated. At the end of his life he settled down in the Catskills, where he painted the series of “The Voyage of the life”.

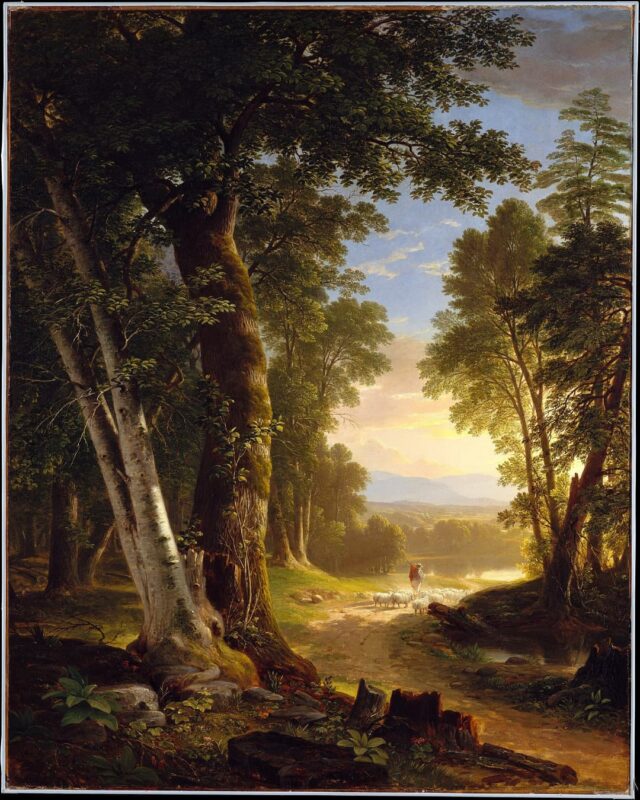

ASHER BROWN DURAND (1796-1886), although older than Cole, introduced himself into landscape painting after studying the works of the previous master. More romantic and less faithful to reality than Cole, his works are arguably more beautiful and poetic, with clear influences of masters like Meindert Hobbema or Claude Lorrain. He is the author of works such as “Kindred Spirits” or “The beeches”.

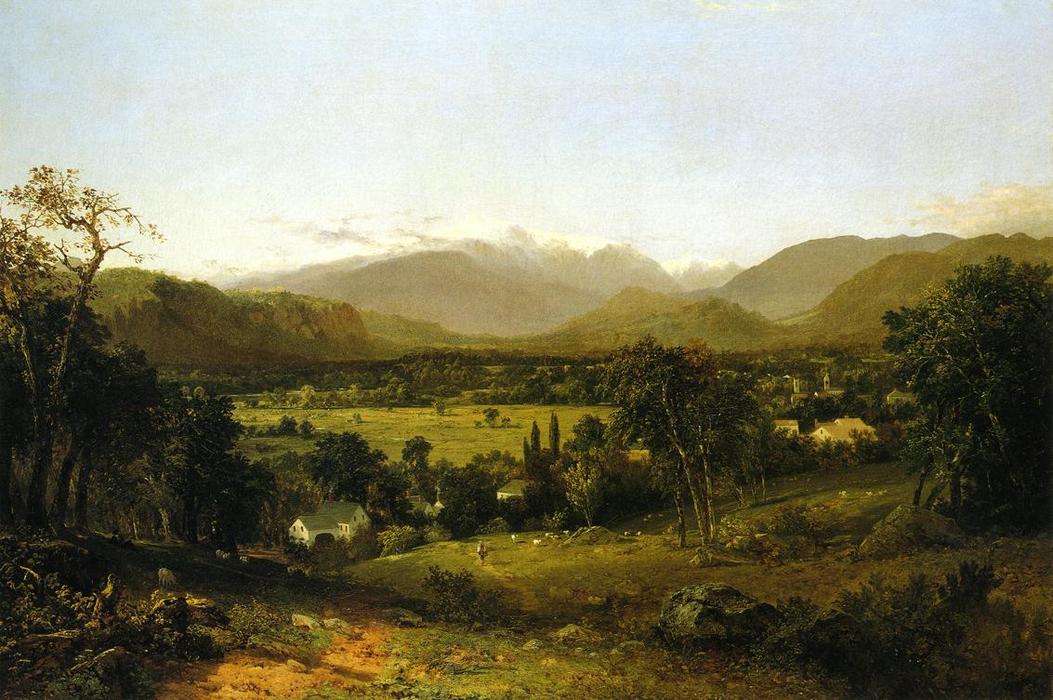

ALBERT BIERSTADT (1830-1902) emigrated from Europe to Massachusetts with his family when he just a young boy. He is one of the first painters who depicted the grandeur of the American West, as we can see in his views of Yosemite Valley, the Kern River Valley or the White Mountains. He is the most prolific and possibly the most grandiloquent of all the American painters of his time.

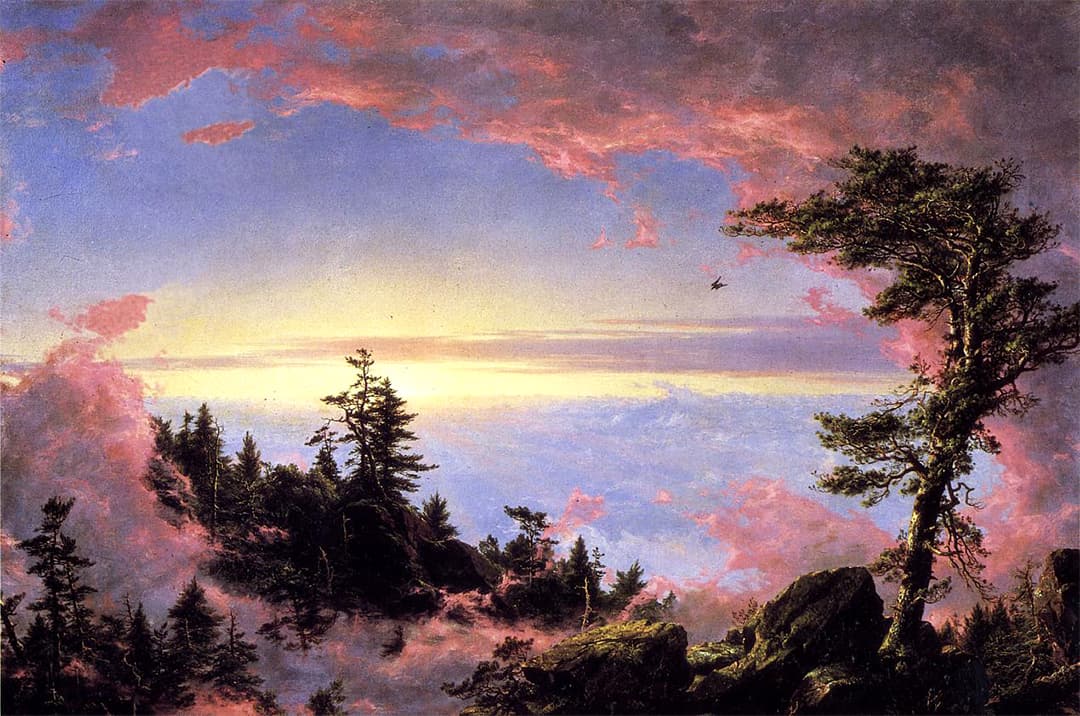

FREDERIC EDWIN CHURCH (1826-1900) was an admirer and disciple of Thomas Cole, to whom he dedicated many of his works. Church represents the culmination of the Hudson River School: he had Cole’s love for the landscape, Asher Brown Durand’s romantic lyricism, and Albert Bierstadt’s grandiloquence, but he was braver and technically more gifted than anyone of them. Church is without any doubt one of the greatest landscape painters of all time, perhaps only surpassed by Turner, the early Chinese masters, and some impressionists and postimpressionists like Monet or Cézanne.. Later in his career, the North American landscape was not enough for Church, and he painted exotic masterpieces like “Cotopaxi”, “Chimborazo” or the oneiric “Above the clouds at sunrise”.

Other significant painters were SANFORD ROBINSON GIFFORD (1823-1880), perhaps the most gifted painter of the second generation (after Bierstadt and Church, of course), JOHN FREDERICK KENSETT (1816-1872), a great seascape painter and a loyal depicter of Mount Washington, WILLIAM TROST RICHARDS (1833-1905), WORTHINGTON WHITTREDGE (1820-1910), of German origins like Bierstadt, JASPER FRANCIS CROPSEY (1823-1900) or MARTIN JOHNSON HEADE (1819-1904), attracted, like Church, by the exotic landscapes.

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT: SOCIETY AND VALUES IN THE AMERICA OF THE 19th CENTURY

When the Hudson River School was at its peak, the United States was still a young nation in the middle of its development (actually, some of the states that today form the American West had not been annexed at that time). In addition, between 1861 and 1865 the young nation suffered a cruel Civil War that put in danger its unity and even the bases of its existence. It was for that reason that, after the end of the War, the painters from the victorious North wished to find in the monumental natural scenes the ideal representation of a united Nation and the durable peace of the aftermaths of the Civil War.

In order to create the American identity, writers and artists wanted to separate from the European tradition. Figures like Emerson, Thoreau or Whitman put special emphasis on the idea of creating a North American culture fully independent of the European one, which -translated to the Hudson River School- meant the development of an American landscape painting tradition, goal and objective of all the Hudson River School painters. But, paradoxically, all these cultural figures also felt eally attracted to the European culture, to which they made constant references. Something similar happened with painters: although several of its protagonists -in special the first master, Thomas Cole- claimed that European landscape was “vulgar” and “empty” when compared to America, very few painters -perhaps only Bierstadt and Church, both in their maturity- were able to free themselves of any reminiscence of the European landscape, and reached the goal of creating an “essential” American landscape.

In addition, we must not forget the subtle but vital importance that religion had in the American society and Art of the 19th Century. We are going to explain something more of this complex subject in the following chapter.

LANDSCAPE AS DIVINE WORK / LANDSCAPE AS HUMAN WORK

“The true province of Landscape Art is the representation of the work of God in the visible creation, independent of man, or not dependent on human action”

Asher Brown Durand, 1849

“There are, properly, but two styles of landscape-gardening, the natural and the artificial. One seeks to recall the original beauty of the country (.) But you will understand that I reject the idea of ‘recalling the original beauty of the country.’ The original beauty is never so great as that which may be introduced”

Edgar Allan Poe

The Dominion of Arnheim (the garden-landscape), 1847

The importance of religion is evident in the great landscape painters of the American 19th century, who saw in the grandeur of the nature the unmistakable hand of Divinity. However, the religious implications of the painters of the Hudson River School are more complex and less evident than we could expect. As Alfred Kazan has pointed in its essay “God and the American writer” (1997), the religiousness of American writers – or painters- was at the time deeply personal and heterodox, in whom the natural elements practically acquired the category of divinity. In this sense, it is not preposterous to suggest that this pictorial transcendentalism is closer to the beliefs of the Native Americans than to the Christian tradition.

Opposed to this defence of the “divine” and wild nature, never altered by the man, Edgar Allan Poe wrote in 1847 “The Domain of Arnheim”, known in his first version as “The landscape Garden”, in which he defended the modification of the landscape by modern civilization. Nature, for Poe, was not perfect, having defects that could -and should– be modified by the artist. But not even this idea is free of the divine hand, rather it is “a Nature which is not God, nor an emanation of God, but which still is Nature, in the sense that it is the handiwork of the angels that hover between man and God” (Edgar Allan Poe, “The Landscape Garden“)

THE PRIMITIVE MAGNETISM OF THE WILDERNESS

“Life consists with wildness. The most alive is the wildest. Not yet subdued to man, its presence refreshes him.”

Henry David Thoreau, Walking, 1862

“The bleak splendours of these remote and lonely forests rather overwhelmed him with the sense of his own littleness. That stern quality of the tangled backwoods which can only be described as merciless and terrible.”

Algernon Blackwood, The Wendigo, 1910

The resource of depicting the wild nature, the savage and overwhelming nature, as a recurrent element in landscape painting is not a creation of the Hudson River School. If we want to look for an origin within the Western tradition, we must look at the early European romanticism, with painters such as Caspar David Friedrich using the disturbing contrast between the immensity of the nature and the insignificance of a single human being (see “Monk by the sea”, 1809, or “The Chasseur in the Forest”, 1814). But in American painting, a simultaneously attractive and disquieting element is included: in addition to the grandeur of the nature is the fact of that the greatest part of that natural area was still unexplored. In fact, almost the totality of which today is southern Canada was covered with a neverending coniferous forest from which the only information known was the Indian legends about the spirits that inhabited these vast lands, as Algernon Balckwood suggestively narrated in “The Wendigo”

“He remembered suddenly how his uncle had told him that men were sometimes stricken with a strange fever of the wilderness, when the seduction of the uninhabited wastes caught them so fiercely that they went forth, half fascinated, half deluded, to their death.”

The original inhabitant of these “wild lands” was – of course- the American Indian people. In Thoreau’s words, “The Indian…stands free and unconstrained in Nature, is her inhabitant and not her guest, and wears her easily and gracefully. But the civilized man has the habits of the house. His house is a prison”. Therefore, the way of life of the American Indian people, living in harmony with the natural surroundings, became a recurrent subject for the American landscape painters, especially Albert Bierstadt and Ralph Albert Blakelock. But even in these “indian” paintings, the human being, the American Indian, does not seem to be the main protagonist of the composition, but just another element within the grandiloquence of the surrounding nature.

REAL LANDSCAPE / FANTASY LANDSCAPE

The gorgeous fluvial valley of the Hudson River was not the only natural protagonist in the paintings of the artists from this School. Many natural monuments of the Northeast also took part in this particular natural iconography, including Mount Washington and the Adirondacks. In addition, it is necessary to mention that several painters from the second generation focused on seascapes, skilfully portraying the coasts of Connecticut or New Hampshire, like Fitz Hugh Lane or John Frederick Kensett.

But the true Mecca of Western landscape painting, there where the American landscape was found in its maximum splendour, was the American West. And these Western lands were the home to painters like Herman Herzog, Thomas Hill, and, over all of them, Albert Bierstadt.

In addition, we need to mention two painters whose ambition was not satisfied only with the North American landscape (not even with the magnificent West), and travelled to the exotic South America in search of exuberant landscapes: Frederic Edwin Church and Martin Johnson Heade. The first of them is the author of works that combine an absolute technical perfection with a colossal and heroic vision of the magnificence of the tropical landscapes, as we can see in the spectacular “Cotopaxi” (1862). His fantastic “Heart of the Andes” (1859) was sold to the Metropolitan Museum of New York shortly after being painted for 10,000 US dollars, then the highest price ever paid for a work by a living American artist. Contrasting with these exotic tropical paintings, Church also represented the frozen beauty of the Arctic, like in “The Icebergs” (1861), one of his supreme masterpieces. On the other hand, Heade was deeply attracted to the tropical landscape, either the South American jungles (“Cattelya Orchid and Three Brazilian Hummingbirds”, 1871) or the Florida marshes (“The Great Florida Marsh”, 1886).

But opposed to these natural and virgin landscapes, and perhaps related to the already commented idea of “improving” the natural landscape, many painters from the Hudson River School often resorted to the imagined landscape as a way to give the nature a grandiloquence that was beyond reality. Thomas Cole exemplifies this in his fantastic “Expulsion from the Garden of the Eden” (1827/28), in which he combined clearly moralizing elements with a visual fantasy comparable to the texts of Edgar Allan Poe, who wrote this sensational depiction of a fantasied landscape in “The Domain of Arnheim”: “Meantime the whole Paradise of Arnheim bursts upon the view. There is a gush of entrancing melody; there is an oppressive sense of strange sweet odor,-there is a dream-like intermingling to the eye of tall slender Eastern trees-bosky shrubberies-flocks of golden and crimson birds-lily-fringed lakes- meadows of violets, tulips, poppies, hyacinths, and tuberoses-long intertangled lines of silver streamlets-and, upspringing confusedly from amid all, a mass of semi-Gothic, semi-Saracenic architecture sustaining itself by miracle in mid-air, glittering in the red sunlight with a hundred oriels, minarets, and pinnacles; and seeming the phantom handiwork, conjointly, of the Sylphs, of the Fairies, of the Genii and of the Gnomes.”

EPILOGUE – THE INHERITANCE OF THE HUDSON RIVER SCHOOL

The Hudson River School had few repercussions in later European painting, where the landscape painting tradition had sources as old and consolidated as Dutch painting, Northern Romanticism or the Realism of the Barbizon School. Nevertheless, in the United States its influence was highly important, going beyond painting and influencing the way in which Americans related to nature. A short walk through Central Park -a park created following the spirit of the Hudson River School- is enough to understand this idea.

Follow us on: