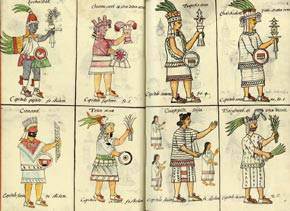

Aztec Deities

Bernardino de Sahagún

Spanish, 1499–1590

Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España (General History of

the Things of New Spain), also called the Florentine Codex vol. 1,

1575–1577

Colonial Mexican

Watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding

Open (approx.): H: 32 x W: 43 cm (12 5/8 x 16 15/16 in.)

Object (above deck, approx.): H: 16 cm (6 5/16 in.)

Closed: H: 32 x W: 22 x D: 5 cm (12 5/8 x 8 11/16 x 1 5/16 in.)

VEX.2010.2.28

Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Italy, FI 100 Med.Palat.

218

Su concessione del Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali.

È vietata ogni ulteriore riproduzione con qualsiasi mezzo.

Xochipilli. Aztec, 1450–1521; found in Tlalmanalco. Basalt. Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City, Mexico, 10-222116 0/2. CONACULTA-INAH-MEX © foto zabé. Reproduction authorized by the National Institute of Anthropology and History.

The Aztec Pantheon and the Art of Empire

Celebrating the bicentennial of Mexican independence, The Aztec Pantheon and the Art of Empire reveals a defining moment of cultural encounter. In the sixteenth century, European exploration and colonization in the Americas coincided with the Renaissance rediscovery of classical antiquity, and parallels were routinely drawn between two great empires—the Aztec and the Roman.

from March 24 through July 5, 2010

]]>

Source: Getty Museum

The Aztec Pantheon and the Art of Empire, on view at the Getty Villa from March 24 through July 5, 2010, represents the J. Paul Getty Museum’s first display of antiquities from outside the ancient Mediterranean as well as the first exhibition on the Aztec empire to be organized in Los Angeles. Masterworks of Aztec sculpture, largely from the collections of the Museo Nacional de Antropología and the Museo del Templo Mayor in Mexico City, are the point of departure for this exploration of the monumental art of empire.

Among the most spectacular objects in the exhibition is a green porphyry sculpture from the Museo Nacional de Antropología depicting the decapitated head of the warrior goddess Coyolxauhqui, whose death at the hands of her brother, Huitzilopochtli, represents the origin myth of the Aztec people.

The Florentine Codex—an iconic chronicle of Aztec culture and history from the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence, Italy—returns to the “New World” for this exhibition for the first time in over four centuries and sets the stage for the comparison of the Aztec and Roman pantheons while images of classical gods and mythological figures from the collection of the Getty Museum will suggest cross-cultural approaches to the role of religion and art in empires. Books, maps, and other documents from the special collections of the Getty Research Institute document the reception of Aztec culture in Europe, and will also be presented in the exhibition.

Themes of the Exhibition

The Aztec Empire dominated central Mexico from 1460 to 1519, and tribute wealth poured into the capital city of Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City), enabling artists and architects to create works of remarkable sophistication on a monumental scale. Under the ninth emperor, Motecuhzoma II (familiarly known as Montezuma), the empire reached the peak of its size and power. When the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés entered the Valley of Mexico in 1519, he witnessed one of the largest metropolises in the world at that time, a cityscape of towering pyramid-temples, floating gardens, and thriving markets. Motecuhzoma’s splendid island-capital appeared to the Spaniards like a dream, compared only to the fabled cities of Jerusalem, Carthage, and Rome.

Confronting an astonishing civilization that found few precedents, Spanish conquistadors and missionaries frequently viewed Aztec culture through the prism of Greco-Roman history, philosophy, and law. The conquistadors’ encounters with the civilizations of the Americas coincided with Renaissance Europe’s rediscovery of classical antiquity. To many Spaniards, the Aztecs were the Romans of the New World. The Aztec Pantheon examines the unexpected contexts in which classicism prompted a dialogue between Mesoamerica andEurope in the 1500s–1700s, when parallels were routinely drawn between two great empires, the Aztec and the Roman.

Following Cortés’s defeat of Motecuhzoma II and the destruction of Tenochtitlan, the Franciscan missionary Bernardino de Sahagún compiled a history of Aztec civilization up to the conquest, known as the Florentine Codex. Sahagún identified the principal Aztec deities with their Roman counterparts: Huitzilopochtli is named otro Hercules (another Hercules), while Tezcatlipoca and Chicomecoatl were likened to Jupiter and Ceres. In this way, Sahagún and his native Aztec collaborators drew upon Greco-Roman mythology to assist Europeans in understanding Aztec religious beliefs. In the 18th century, scholars of comparative religion such as Bernard Picart identified the ancient Mesoamerican deity Quetzalcoatl with the Roman god Mercury, who was similarly associated with commerce and the wind.

“Although Greco-Roman and Aztec cultures are distinct historical phenomena, and developed in isolation from one another, Europeans applied familiar frames of reference to a New World that was largely unfathomable,” explains J. Paul Getty Museum Antiquities Curator Claire Lyons. “Bringing these monumental cult statues, reliefs, and votive artifacts to Los Angeles and showing them in the Roman ambiance of the Getty Villa offers an incredible chance to explore a little-known episode of cultural analogy: the dialogue between the Old and the New Worlds that was sparked in the age of exploration, carried forward during the Enlightenment, and which continues to be informative in the present.”

John Pohl, exhibition co-curator and UCLA professor, adds, “I’m thrilled to have helped bring this exhibition to Los Angeles, a city with such a significant historical connection to the nation of Mexico and its people. It’s long overdue and provides a unique occasion for a major institution like the Getty not only to recognize the sophistication of Aztec art, but to present it alongside the great artistic traditions of Greece and Rome.”

Follow us on: