Monet and the Sea

The seascapes by Claude Monet

by G. Fernández – theartwolf.com

The artistic oeuvre of the Impressionist painter par excellence, Claude Monet, seen through his seascapes. A fascinating virtual tour through the relationship between the impressionist master and the sea.

The beginnings: childhood in Le Havre

The relationship between Monet and the sea began as soon as the young artist moved, along with his family, to the coastal town of Le Havre, Normandy, in the mid-1850s. In these early years Monet did not feel an immediate attraction for “plen air” painting, and he focused in drawing caricatures of neighbors and acquaintances. But his young talent caught the attention of a painter who had established himself in Le Havre years earlier, Eugene Boudin, still considered one of the greatest seascape painters of the 19th century. After a few months, the master convinced the young artist to accompany him on his outings to paint outdoors. The tenacity of Boudin would not be in vain, and Monet recognized, several years later: “If I became a painter, it was thanks to Boudin”

Creating an artist: Jongkind the master

It can be said that the real artistic career of Claude Monet began in 1862, when the painter was just 22 years old. Having become ill in Algeria during his military service, he was sent back to Le Havre to recover. Back in Normandy, the young Monet knew the man who would become, in his own words, his “true master“, Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind.

Alcoholic and impulsive, Jongkind impressed the young Monet with the effects of light and atmosphere in his seascape paintings. The influence of the Dutch painter is clearly perceivable in works like “Pointe de la Hève at Sainte-Adresse” (1864, Currier Museum of Art), with its careful and strongly horizontal representation of the sky and the atmosphere. This painting was admitted in the Salon of 1865. Note the realism of the work and the use of very definite brushstrokes, which Monet later changed in works such as “Rough sea at Etretat” (1868, Paris, Musée d’Orsay)

A bourgeois sea: the terrace at Sainte-Adresse

The works Monet painted in Sainte-Adresse in the second half of the 1860s represent a momentary change in his representation of the sea. Compared with the wild seascapes of previous years (a style that Monet would later resume), here Monet painted the sea as an instrument of entertainment for the bourgeoisie, in a style that can be related with the paintings created for the “Salon des Artistes”, a “genre” that the artist had been developing in previous years, finished with the colossal “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe”, first exhibited in 1866.

“Terrace at Sainte Adresse” is the most representative work of this period. The bourgeois scene is developed under a strong “plein air” light. The clear limits between land, sea and sky divide the composition, vertically organized by the two flags fluttered by the ocean breeze. The painting is so delightful that we are immediately tempted to sit on one of the empty chairs to enjoy this sunny Sunday afternoon. A similar theme, but with a very different composition, is found in “Sailing at Sainte-Adresse” (1867, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Expanding horizons: the trips to England and Holland

It was Durand-Ruel, the great patron of the Impressionist artists, who financially supported Monet, Pissarro and Boudin during their trip to London in 1870, a trip that continued with their stay in the Netherlands the following year. The English landscape did not impress Monet at first; and in fact he painted very few English landscapes, except those depicting the Houses of Parliament and River Thames, a subject that he would resume -in a more enthusiastic way- in subsequent visits. The truly decisive factor in Monet’s stay in London was his visit to the National Gallery, where he discovered the work of the greatest British landscape painters: John Constable and, above all, Joseph Mallord William Turner. Turner’s seascapes, with their effects of light and atmosphere, influenced Monet’s works of the following years.

The French artist made another trip to England in 1899-1900, in his mature years. And although Monet’s visit to the British Islands will always be remembered for the spectacular and famous views of the Houses of Parliament in London, his first stay is a turning point in the biography of the French painter due to the very important influence of Turner in his artistic oeuvre.

What about Netherlands? Well, Netherlands was for Monet ‘love at first sight’. “Everything is more beautiful than we had expected (…). Here are enough landscapes to paint throughout my whole life”, he wrote. Monet was immediately fascinated by the Dutch landscape, and especially by the town of Zaandam, with its boats and windmills. Perhaps the contemplation of the canvases by Hobbema and van Ruysdael made reemerge his early admiration for Jongkind. Or perhaps the love for the pure landscape of these old masters encouraged the artist to look for new challenges. But the truth is that the Dutch influence is visible not only in Monet’s “Dutch” paintings, but also in many of his seascapes created in the coast of Normandy.

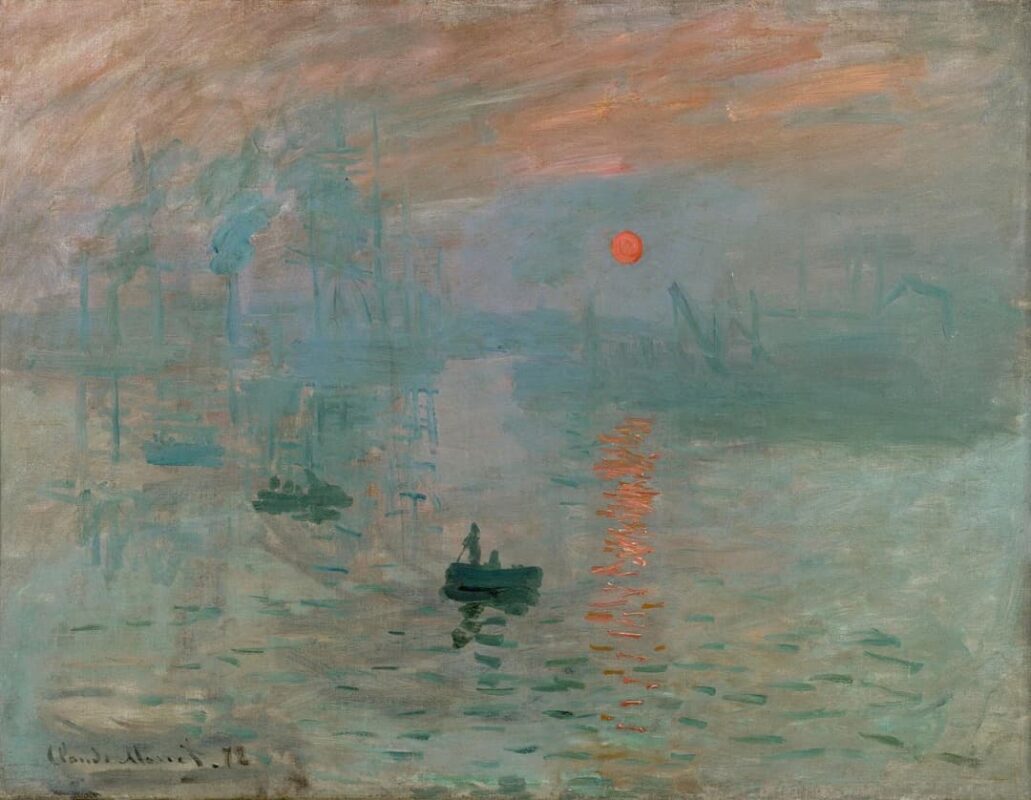

An iconic work: “Impression: sunrise”

“Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape”, Art critic Louis Leroy wrote about this canvas when it was exhibited at the first Impressionist exhibition in 1877. And this is just an example of how most of the critics of the time reacted to this painting, and, by extension, to the whole Impressionist movement (a movement that in fact owes its name to this painting). It is not surprising, then, that nobody offered 1,000 francs, the asking price for the small work.

In the painting, the first thing that draws our attention is the intense fog, which merges all shapes and colors of the canvas, so we can hardly see the chimneys in the background. Even the two boats in the lower part of the canvas seem to be mysteriously floating in an intense sea of fog.

Certainly there is much influence of Turner in this work, both in the atmospheric effect and in the almost contradictory role of the sun, striking but almost powerless in the middle of the vast haze, an effect that recalls the colossal “Hannibal crossing the Alps” by the English painter. But Monet’s impressionist stroke goes even further, giving the surface of the canvas -especially the lower part- an almost abstract quality.

Maturity: the cliffs of Normandy

Between 1881 and 1883 Monet made a series of trips to several coastal towns in Normandy, such as Dieppe, Pourville or Trouville, where the landscapes were enough attractive to satisfy his creative appetite. Unlike in his former seascapes, here Monet seemed to focus more on the coastal landscape than in the ocean itself, taking advantage of the spectacularity of the rugged Normandy coast and its dramatic cliffs.

Almost all conventional seascapes are inevitably horizontally conceived, interpreting the horizon, the limit between sea and sky, as the key element in the composition. Many of Monet works from this period are unique for creating an asymmetrical vertical composition. A good example of this is “Cliffs near Dieppe” (1882, Zurich Kunsthaus Zurich) in which the two traditional horizontal planes (sky and sea) are broken by the dramatic cliff, dividing the composition into two vertical sections (land/cliff and sea). This effect is also notorious in “Beach of Etretat” (1883, Paris, Musée d’Orsay) or the famous “The Manneporte”, in its various versions, but it only reached its maximum effect in the series of paintings we are going to analyze now.

New concepts: customs house at Varengeville

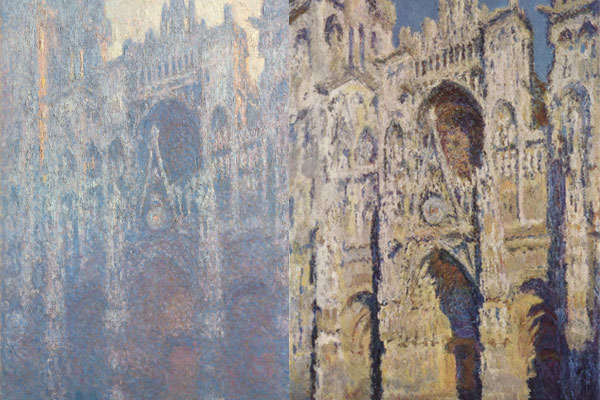

One of the greatest contributions of Claude Monet to modern art was the introduction of the concept of “series”; in which a single subject is represented in various paintings under different conditions of light, weather, etc; so that the represented material subject loses importance when compared to other immaterial elements such as light and color, and to the observation of how these elements vary with time. This concept, later developed by Monet in his “Haystacks” (1891) and “Poplars au bord de l’epte” (1891), and reaching its zenith with the “Rouen Cathedral” (1894); has an important precedent in the several canvases depicting the customs house at Varengeville (1882).

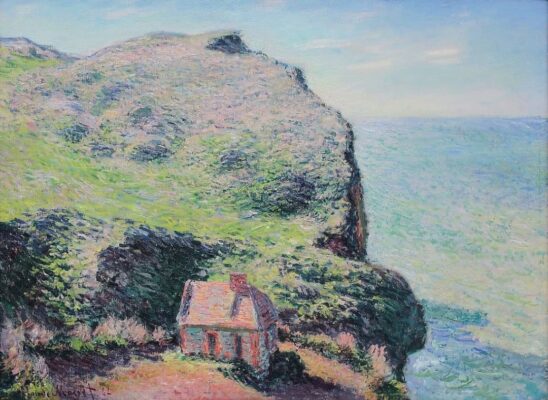

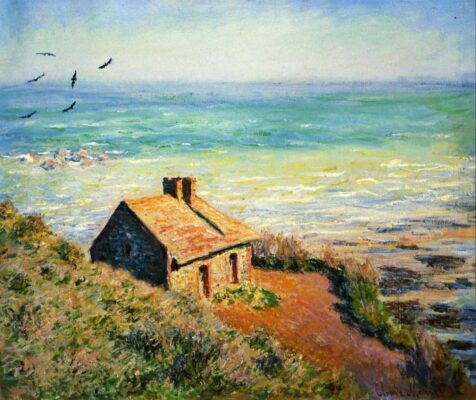

Claude Monet: “Cabane des douaniers, Varengeville” (1882) – Philadelphia, Art Museum ·· Claude Monet: “Cabane des douaniers, effet du matin” (1882) – Private collection

Although not as famous as the well-know series listed above, the analysis of the “Cabane des douaniers” is fascinating. For example, in an example exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art the composition is virtually identical to that of the already commented “Cliffs near Dieppe”, while in an example belonging to an American private collection the dramatic effect of the composition is not only created by the verticality, but it is also reinforced by the asymmetry caused by the diagonal of the cliff.

More than sea and rock: “The Manneporte”

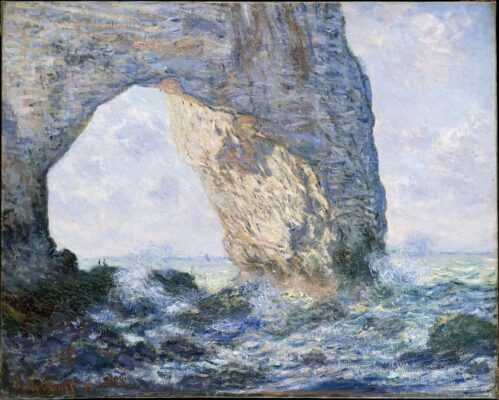

The concept of “series” was explored again by Monet in one of his favorite and most original compositions: the Manneporte, a spectacular natural arch of rock located in a cliff near Etretat. Unlike in his previous works, Monet renounced to paint the environment, and focused exclusively on the dramatic arch and the sea.

Manneporte, photo by Herman Beun ·· Claude Monet: “The Manneporte” (1883) – New York, Metropolitan

In the famous painting exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the meeting point of rock and sea on the left side of the table is very diffuse, so it is very difficult to guess where one begins and the other ends. In another example from this series, now exhibited at the Cleveland Museum of Art, Monet went even beyond and excluded this meeting point from the composition, so the Manneporte seems a colossal column of rock that majestically emerges from the raging ocean. In these paintings we can sense a traces of abstraction, which Monet would further develop in the next decade.

Wild sea, sea of light: from Britain to the Mediterranean

In the second half of the 1880’s, Monet made two trips to various towns in the French coast, trips that were close in time but very far in terms of artistic creation. Thus, in 1886 Monet rented a room in a small hostel near Belle-Ille, where he was immediately fascinated by the “beautiful” but also “frightening” landscape of Coastal Brittany, more violent and fierce than Normandy. In “Storm, Coast at Belle Ille” (1886, Paris, Musée d’Orsay) the ferocious sea waves hitting the rock pinnacles are clearly reminiscent of “The Manneporte”, but this time the surface of the sea plays a greater role, and the thick and powerful brushstroke accentuates the force of the violent storm. This effect of violence and the dark representation of the cliffs are almost a constant in the canvases painted in Brittany.

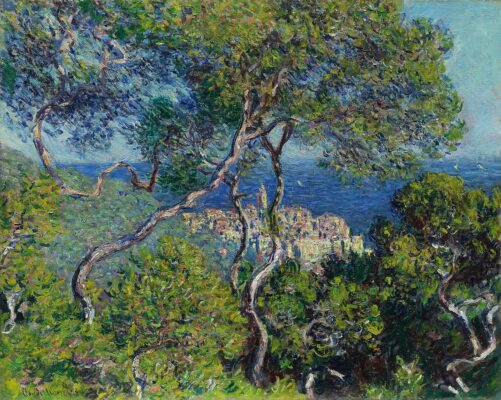

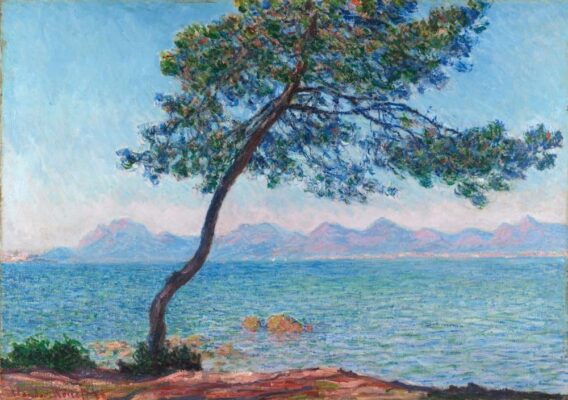

Two years later, Monet rented for three months a small castle in Antibes, in the French Riviera. The artist immediately fell in love with the landscape – “so full of light” – of the Mediterranean, and with the turquoise and pink tones of the Mediterranean light.

Here in Antibes concludes our journey through the relationship between Monet and the sea. The Antibes seascapes were not the last of his career, and in fact in the next decade Monet painted several views of Purville, and even some Scandinavian seascapes during his brief trip to Norway, but they did not represent a key point in his career, already focused on the series of “Haystacks”, “Rouen Cathedral” and “Water Lilies”. And even in works such as those, the results of his experiments developed in his seascape paintings are easily visible.

Claude Monet: “Bordighera” (1884) – Chicago, Art Institute ·· Claude Monet: “Mountains in Esterel” (1888) – London, Courtald Galleries

Follow us on: