Painting the city: the history of cityscapes

Painting the city: the history of cityscapes The history of cityscape painting, from Lorenzetti to Estes, from antiquity to 21st century.

by G. Fernández – theartwolf.com

Any modern or contemporary art lover would recognize that urban landscapes are quite a popular subject in modern art, from the impressionistic views of Paris by Camille Pissarro or Claude Monet to the realistic Madrid of Antonio Lopez, through the photorealistic New York of Richard Estes, or even the abstract landscapes by Willem de Kooning. But, when did this tradition begin? Who have been its main protagonists? This article proposes a journey through the history of cityscape painting, from ancient world to the beginning of the 21st Century.

Ancient world

Just as there is no serious consensus about the exact date of birth of the first city (generally, that has been considered to be Ur or other Mesopotamian cities, but Çatalhöyük, in southern Anatolia could also claim such title), we cannot establish a precise birthdate for cityscape painting.

In Akrotiri, on the Greek island of Santorini, it has been found an enigmatic fresco painting (known as the “Ship procession fresco” or “the flotilla fresco) representing a boat trip between two fortified cities, which nevertheless are not the protagonists of the composition. Something similar happens in the “City Fresco”, an aerial view of a coastal city (real or imagined) found in 1997 at the Baths of Trajan, Rome (see image); which could be considered to be the first complete cityscape in the history of painting. In Stabiae, near Pompeii, some Roman frescoes partially depicting a coastal city have been found.

The pioneers: from the Trecento to the High Renaissance.

During the Middle Ages, partial representations of cities can be found as backgrounds in many illuminated manuscripts, without ever achieving a special role in the composition. In the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century, Western painting began to revive. Thanks to Duccio da Buonisegna, Cimabue, and, above all, Giotto di Bondone, European painting is “freed” from the rigid Byzantine tradition, renewing its soul and exploring new ways. Ambrogio Lorenzetti (c.1290-1348) painted in 1335 the fresco known as “City by the Sea” (Pinacoteca, Siena), generally considered to be the first true cityscape of the history of Western Art. But even more remarkable is his “Allegory of Good Government” (c.1338-40, Palazzo Publico, Siena), which, with its many chromatic layers lacking any perspective, seems to enigmatically anticipate some paintings from the early 20th century avant-garde, like those by Schiele and Klimt .

This interest in cityscape painting started by Lorenzetti did not create a continuous or remarkable tradition in Italy (although small but bright cityscapes appear as backgrounds in some works by the most famous painters of that era, as we can find in “Saint Helena and the Holy Cross” by Piero della Francesca) until late Quattrocento. At that time, some Venetian painters, most notably Vittore Carpaccio and Gentile Bellini, created what can be considered the first “golden age” of cityscape painting in Western Art, a short-lived but remarkable prelude to “vedute painting”, which we are going to study in a forthcoming chapter.

Nor was there a tradition of cityscape painting in Northern Europe, although, as it happened in Italy, many of the most important painters of that era included beautiful representations of cities as a background in many of his paintings, such as Albrecht Altdorfer in the spectacular “Battle of Alexander at Issus” (1529). However, the most remarkable experiments in urban landscapes in Renaissance Germany were carried out by printers and engravers, especially Michael Wolgemut (1434-1519)

In the very detailed “Madonna of Chancellor Rolin”, Jan van Eyck included at the bottom of the composition a stunning representation of a river city, possibly Lyon (France). But despite the quality of this representation, the city does not reach a “leading role” status in the painting, just like in the “Saint Ursula Shrine” by Hans Memling. Generally, Dutch painting, with notable exceptions such as Maarten van Heemskerck (1498 – 1574), did not show a great interest in urban landscape painting till an important turning point that we are going to study in the next chapter.

The establishment of cityscape: the Delft School

The beautiful city of Delft, in Western Netherlands, had caused a special admiration among painters since the end of the Renaissance, appearing in works such as “Delft Vanuit het Westen” (c.1615), by Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom (1566-1640). But it was during the second half of the seventeenth century, after the catastrophic explosion that happened in the city in 1654 (notably represented by painter Egbert van der Poel in “Explosion in Delft”), when the “Delft School” reached its zenith.

The most prominent artist of this school is Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675). By no means a prolific painter, only 35 works can be attributed with certainty to the artist. And, among them, there are two cityscapes that can be considered among the most important ever painted. The first is the famous “View of Delft”, which Marcel Proust considered to be “the most beautiful picture in the world.” In it, the incredible precision with which the artist painted the architecture of Delft made several critics to suggest that the artist had used a camera obscura, although this fact has not been confirmed. Less famous than the previous work, “A street in Delft” (also known as “The little street”, 1661, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) combines a seemingly simple composition with several elements, such as the marked asymmetry of the composition or the focus on everyday life, which seems to anticipate the style of twentieth-century cityscapes.

Canaletto and the vedutistas

During the early eighteenth century, it was usual among the wealthy British businessmen to make a trip to the major Italian cities, including Venice; a trip known as the “Grand Tour”. Desiring to return to the rainy north with a worthy souvenir of the Venetian light and architecture, travelers were eager to acquire views of the “City of the Channels” painted by local artists, thus promoting the formation of a new genre painting, the Vedute. Heirs of the aforementioned Venetian painters from the late Quattrocento and early Cinquecento (Carpaccio, Bellini), vedute painters did not need “excuses” (like royal or papal receptions) to include the city in his paintings: Venice –its light, its architecture- is the one and only star of the composition.

The exhibition “Canaletto and his rivals”, organized by the National Gallery of London in 2010, clearly shows the hierarchy between these painters: the famous Canaletto is properly at the pinnacle, an artist able to “make the sun shine in his paintings”, as a 18th century art dealer said to one of his customers. Canaletto’s popularity among the British businessmen took him to England, where he increased his fame and fortune by painting urban landscapes in London. In addition to Canaletto, we should mention two important predecessors, Gaspar van Wittel (Dutch born artist who later moved to Italy) and Luca Carlevarijs, as well as the two most talented followers of Canaletto, Bernardo Bellotto and Francesco Guardi.

Cityscape in Asia

There is not a continuous tradition of cityscape painting in Chinese Art (more focused on natural landscape), prior to the 20th century. There are, of course, very remarkable exceptions: the stunning “Along the River during the Qingming Festival” (1085-1145), by Zhang Zeduan, shows (with a level of detail difficult to conceive for such an ancient work) the daily life in a small river village in China. Other later artists also included view of small cities -almost always surrounded by stunning natural landscapes- in their paintings, as it can be seen in “The new City of Feng” (c.1760) by Ding Guanpeng. Cityscapes are, however, a fundamental part of contemporary Chinese art.

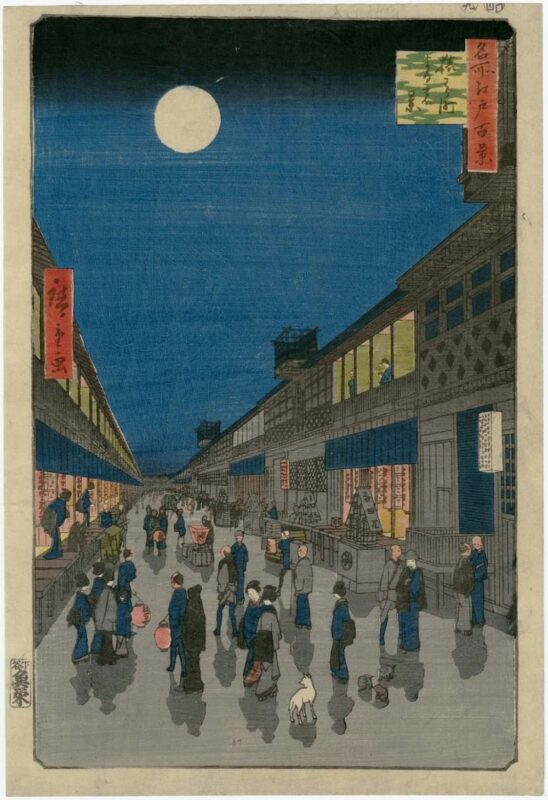

In Japan, the turning point to cityscape painting is marked by the Edo Period (1603-1868), when urban culture was born, reflected in the paintings by artists such as Utagawa Hiroshige, also known as Ando Hiroshige, author of the nice “Night view of Saruwakacho” (1856), and other lesser known painters like Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

Impressionism

During the second half of the 19th century, the city of Paris undertook a group of reforms affecting its interior morphology, with the aim of transforming the French capital into the most modern and powerful European metropolis. Napoleon III appointed Georges-Eugène Haussmann as the responsible of this ambitious project -later known as “Haussmann’s Paris”. After this modernizing boost, Paris turned into one of the favorite pictorial subjects for the impressionist painters. From Manet to Caillebotte, from Renoir to Pissarro, and even a “not so impressionist” painter like van Gogh, the new Paris was chosen as a model for modern paintings.

In addition to general views of the city, including the famous “Paris Street, Rainy Day” by Gustave Caillebotte (1877, Paris, Musée d’Orsay) and the spectacular “The Boulevard Montmartre at Night” by Camille Pissarro (1897, London, National Gallery), Impressionist painters were also attracted by the innovative elements of the modern city, especially those related to the railway world. Thus, rail stations became a central part of the Impressionist “iconography”. And among them, the Saint-Lazare Station (“le Gare Saint-Lazare”) fulfilled all the impressionist ambitions. The sensational “Le gare Saint Lazare (Saint Lazare station)” (1877, Paris, Musée d’Orsay) by Claude Monet, was admired even by critics of that time, something unusual in the Era of Impressionim. The aforementioned Gustave Caillebotte was another painter who was clearly fascinated by the railway world, as it can be seen in one of his most famous paintings, “The Bridge of Europe” (1876, Musée du Petit Palais, Geneva)

Painting the American city: from Whistler to Diebenkorn

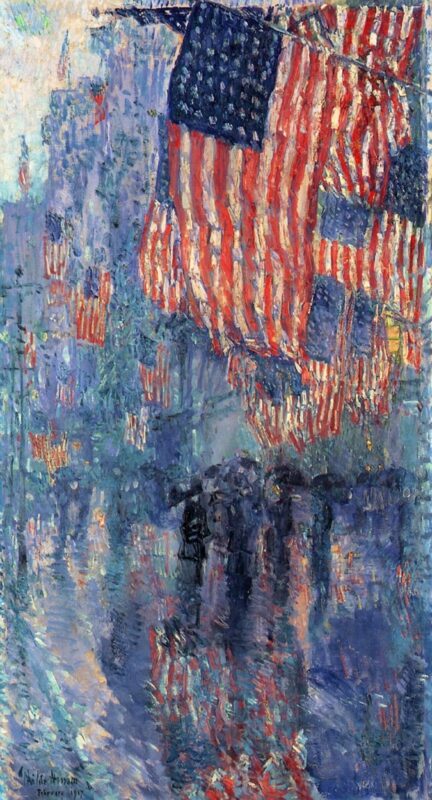

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), one of the most prominent 19th century American painters, is also the most important figure in American cityscape painting of his era. His night views of American and European cities reached their zenith in the sensational “Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket” (1874, Detroit Institute of Arts). After Whistler, the most notable painter in such genre is Childe Hassam (1859-1935), one of the most representatives figures of American Impressionism, whose paintings of “flags” (most notably “The Avenue in the Rain”, 1917) still rank among the most easily identifiable icons of American painting.

A peak in the history of cityscape painting is reached with the apparition of the “Ashcan School”, a group of American realist painters focused on depicting everyday life in the early 20th century New York City. The first leader of this generation of artists was Robert Henri, creator of iconic works such as “Snow in New York” (1902, National Gallery of Art, Washington), and who was followed by important artists like Everett Shinn and John French Sloan.

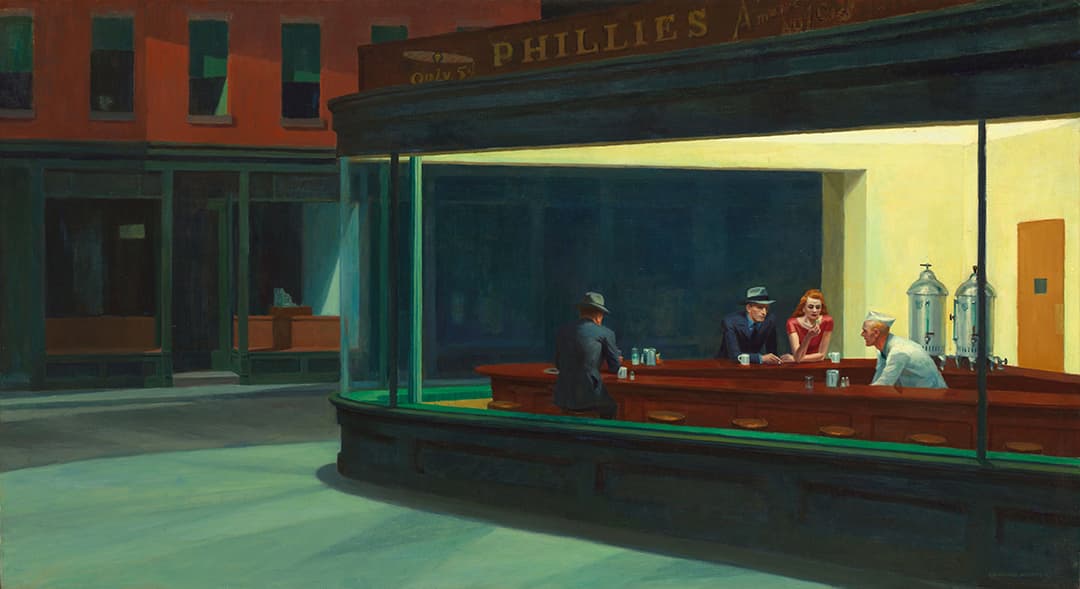

But the two most important artists of this generation are George Bellows and Edward Hopper. Bellows, a talented painter with a very active social conscience, is the great narrator of the life of the New Yorker’s lower-middle class of his time, reaching his greatest achievements in “Cliff Dwellers” (1913, Los Angeles, County Museum of Art) and the sensational “New York” (1911, National Gallery of Art, Washington). Hopper, meanwhile, will always be regarded as “the painter of urban loneliness”, preferring the scenes that take place inside hotels and apartments, and the author of the famous “Nighthawks” (1942, Art Institute of Chicago)

Urban landscape and avant-garde

Cityscapes from the avant-garde period are as varied as the actual art scene of that time. In other words, impossible to summarize in an article like this. Let us briefly review the most significant avant-gardes of the time and their relation with cityscape painting.

Among all cubist painters, the one who devoted most of his oeuvre to cityscape painting is Fernand Leger, being “The City” (1919, Museum of Art, Philadelphia), his most significant work, in addition to one of the finest urban landscapes ever painted. A very painterly, though more “usual” cityscape is “Champ de Mars, The Red Tower” (1911, Chicago, Art Institute), by Robert Delaunay.

Many painters from the so-called “School of Paris” also created their unique visions of the French capital. From the colorful works of Henri Mattisse (“Arab city”, 1905) and Raoul Dufy (“Street Decked with Flags”, 1906, Le Havre, National Museum) to the very personal works by Marc Chagall, especially “Paris through the Window” (1913), in which the artist depicts a mysterious and indecipherable Paris in which nothing -or nobody- is really what they appear to be. We must also mention Italian Futurists, tenacious in their efforts to represent the movement of the contemporary city (Umberto Boccioni: “The City Rises”, 1910-11, New York, Museum of Modern Art)

In the years immediately following the First World War, in Germany, we have the figure of George Grosz, an enigmatic painter, sometimes labeled as a “dada” artist, which is the easiest way of describing such an unclassifiable artist. In works like “Metropolis” (1917, New York, MOMA) and “The funeral of Oskar Panizza” (1917-18, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart), Grosz ruthlessly depicted the urban society of his time, dazed and disoriented after the recent violence of War.

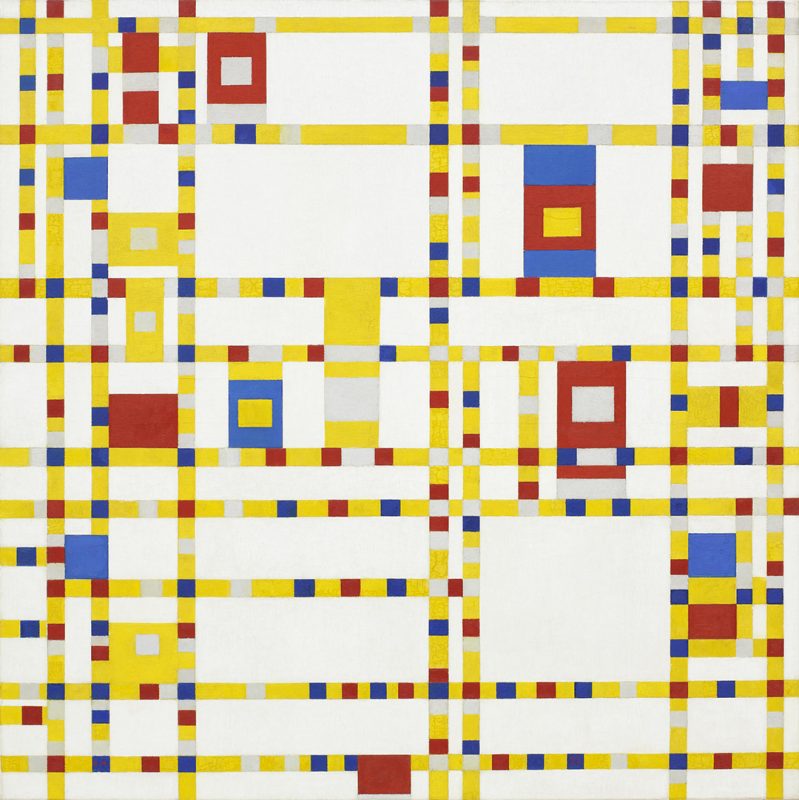

On the way to abstraction we find the figure of Piet Mondrian, who, after emigrating to the United States, created his original visions of New York City, among them the famous “Broadway Boogie Woogie” (1942-43, New York, MOMA) , which the painter Robert Motherwell described with these words: “The Modern City! Precise, rectangular, squared, whether seen from above, below, or on the side; bright lights and sterilized life; Broadway, whites and blacks; and boogie-woogie; the underground music of the at once resigned and rebellious”.

The contemporary city: photorealism and hyperrealism

Cityscape painting flourished after World War II, already appearing in the repertory of abstract expressionist painters, for example in “City landscape” by Joan Mitchell (1955, Art Institute of Chicago) or in some audacious pictorial experiments by Willem de Kooning.

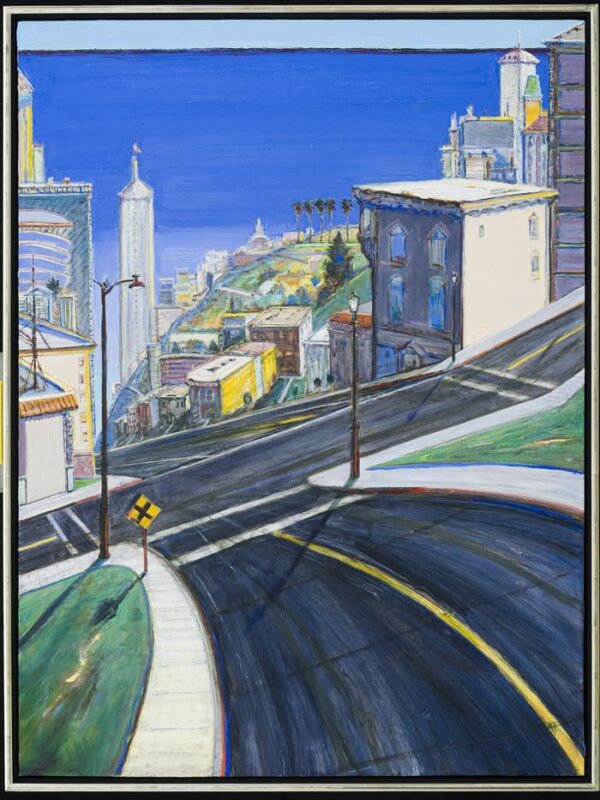

Departing from the dominant abstract expressionism of the late 40’s and early 50’s, the painters of the “Bay Area Figurative Movement” resorted to figurative painting to depict the light of the West Coast. Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993) adopted the style of abstract expressionism early in his career, but soon changed to figurative language (“Cityscape I”, 1963, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art). Wayne Thiebaud, famous for his paintings of toys and candies, is also well known for his views of avenues and huge highways in California, an artistic production in which he is still active today.

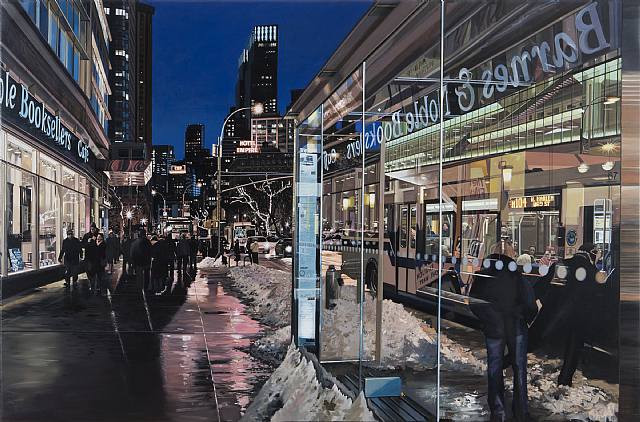

But arguably the most important contribution to cityscape painting in recent times has been made by photorealist and hyperrealist painters. Within the first group, the most important figure is Richard Estes (born 1932), possibly the most important New York cityscapes painter since George Bellows, whose artistic production spans from the brilliant “Horn and Hardart Automat” (1967) to the recent “Broadway Bus Stop, Near Lincoln Center” (2010).

© Richard Estes, ARS New York

courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York

In addition to Estes, we should mention the works of Rackstraw Downes (born 1939), a British-born artist working in New York, and Yvonne Jacquette (born 1934), known for her many aerial views of the great American cities. And among the hyperrealist painters, we must mention Antonio Lopez, Spanish painter whose “Gran Vía” (1974-1981) is already part of the history of Spanish painting, and an icon of hyperrealist painting.

© Antonio López

Follow us on: